In a 2015 lecture at Harvard Law School for something called the “Antonin Scalia Lecture Series,” Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan lauded her colleague for his role in mainstreaming textualism, his chosen method of statutory interpretation. Textualism, she explained, transformed a previously “policy-oriented” task to one in which judges, no longer “pretending to be congressmen,” are “unable to rewrite the text” of the statute they are analyzing. Kagan then issued what would become a famous proclamation: “We’re all textualists now.”

Clip via YouTube

Seven years later, in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, the Court’s conservatives purported to use textualism to pump the brakes on mitigating impending climate disaster. In an opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Court claimed that Congress hadn’t written the text of the Clean Air Act “clearly” enough to allow the EPA to implement a certain emissions reduction strategy. By vetoing the agency’s determination of the “best system of emission reduction for power plants,” the Court’s conservative majority effectively reserved that power for itself.

In a scathing dissent joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer, Kagan walked back her earlier assessment. “It seems I was wrong,” she wrote. “The current Court is textualist only when being so suits it.” The majority’s real goal, she said, was clear: to weaken the administrative state and “prevent agencies from doing important work, even though that is what Congress directed.”

Scalia, who died in 2016, defined textualism as a statutory interpretation method that focuses on the original “ordinary public meaning” of a law’s text at the time of its passage. He claimed that textualism, (ostensibly) much like the related concept of constitutional originalism, prevents unelected, unaccountable judges from writing laws from the bench.

Deciding how the public would have understood a statute’s text, of course, requires that judges act as amateur historians and parse its meaning accordingly. And although textualism purports to be objective, considering how amorphous “the public” is, the doctrine actually invites judges to imbue the law with their own biases, predispositions, and beliefs. Textualism is thus one of the conservative legal movement’s most ingenious inventions: a formalistic tool enabling conservatives to declare that a fair, neutral application of the law compels their preferred policy outcomes. Kagan’s disavowal of the philosophy as selective and hollow in West Virginia is right. It also comes years too late.

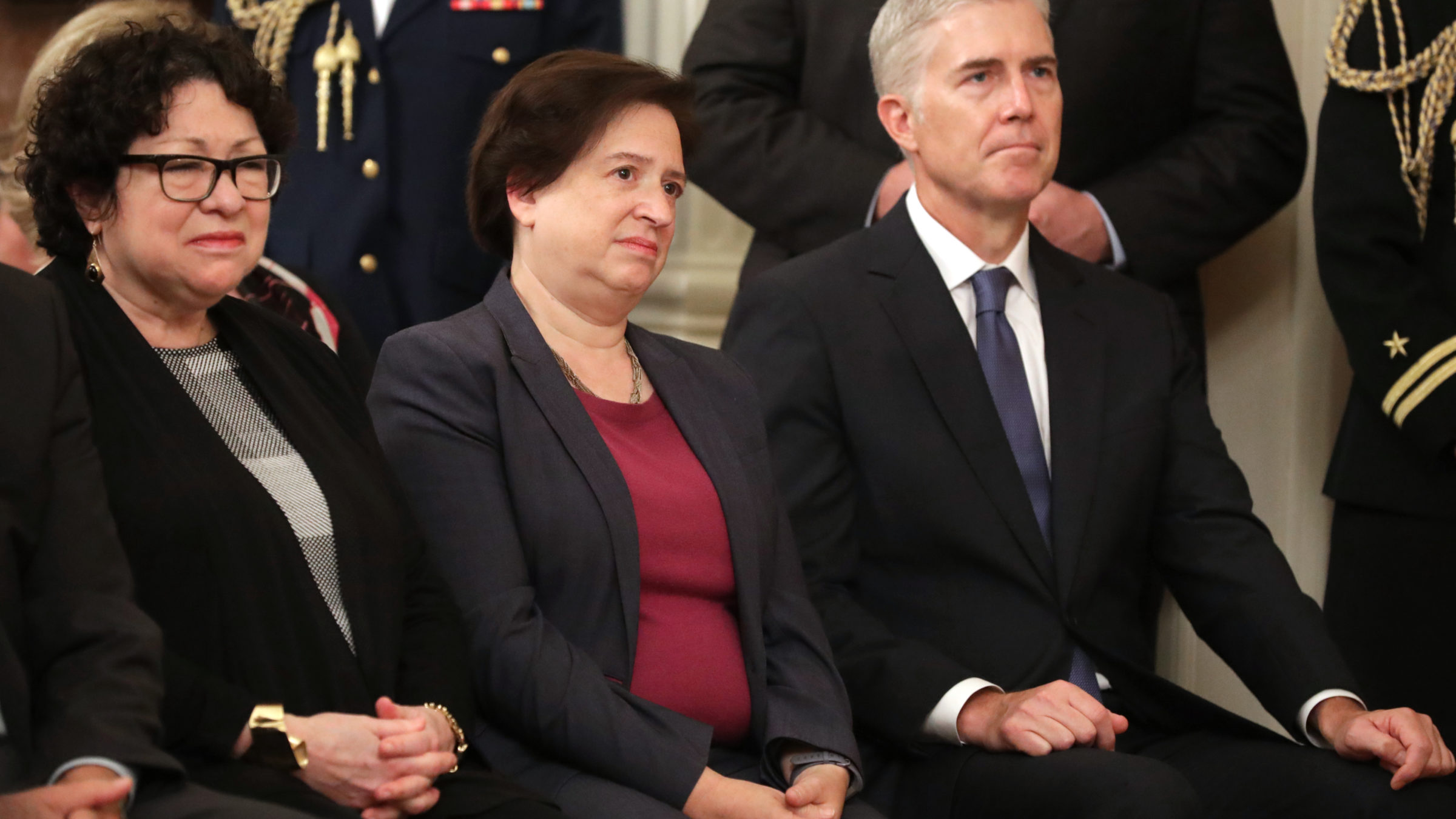

Just a couple of textualist buds (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The conservative commentariat’s uproar over Bostock v. Clayton County in 2020 was a rare moment of transparency about what textualism was always intended to do: reach conservative outcomes. The opinion, written by Justice Neil Gorsuch and joined by Roberts and the liberal justices, held that existing federal civil rights laws protect queer and trans people from “sex-based” workplace discrimination.

Although the law at issue does not explicitly mention LGBTQ status, the opinion focused on the meaning of the word “sex.” Because discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation “requires an employer to intentionally treat individual employees differently because of their sex,” Gorsuch wrote, the law extends to LGBTQ people, too.

Upon seeing their pet theory yield a single non-reactionary agenda item, the conservative legal movement’s luminaries promptly lost their goddamn minds. Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas dissented, calling the opinion “preposterous” and akin to a “pirate ship” flying under a textualist flag. Missouri Senator and noted amateur track athlete Josh Hawley declared the decision “the end of the conservative legal movement.” If Bostock is a textualist decision, he added, “then I have to say it turns out we haven’t been fighting for very much.”

Hawley needn’t have worried. At this point, the liberal justices, too, have thoroughly accepted the legitimacy of textualism, even when the methodology’s application means, for example, locking away asylum-seekers for years on end. This past term, in an 8-1 opinion written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the Court held in Johnson v. Arteaga-Martinez that certain immigrants in federal detention aren’t entitled to bond hearings, placing great weight on the fact that the statute’s text does not “even hint” at such a requirement.

Sotomayor’s approach in Arteaga-Martinez contrasts with that of Justice Stephen Breyer in 2001’s Zadvydas v. Davis, when the Court imposed a six-month limit on detention for people whose deportation is not imminent. Although the government argued that the statute, which contained no express time limit, “means what it literally says,” Breyer reasoned that “a statute permitting indefinite detention of an alien would raise a serious constitutional problem.” Two decades later, liberals lacked the stomachs for the fight.

Textualism is a major part of what fuels the conservative legal movement’s success in the courtroom. Thanks to liberal acquiescence to its legitimacy, however, the Supreme Court’s conservatives don’t even need to bear the burden of, say, enabling the government to lock up immigrants indefinitely. Their liberal colleagues are happy to help them carry it.