On Monday, the Supreme Court declined to hear two cases challenging the constitutionality of state-level bans on assault-style weapons and large-capacity magazines. One appeal, Snope v. Brown, concerned Maryland’s law banning AR-15s, AK-47s, and similar guns, which state lawmakers enacted after a man with a semiautomatic rifle walked into Sandy Hook Elementary School and gunned down twenty first graders and six adults. The other appeal, Ocean State Tactical v. Rhode Island, contested the legality of Rhode Island’s ban on magazines holding more than 10 rounds, which lawmakers passed weeks after the back-to-back mass shootings in Buffalo, New York, and Uvalde, Texas in 2022.

Because the Court declined to take up these appeals, lower court decisions upholding the laws remain undisturbed—for now. But Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas all dissented in both cases, meaning they wanted to grant the gun groups’ petitions right now. “I would not wait to decide whether the government can ban the most popular rifle in America,” said Thomas in a standalone dissent in Snope. “I cannot see how AR–15s fall outside the Second Amendment’s protection.”

Thomas’s argument is that Maryland’s ban can’t clear the hurdles the Court imposed in NRA v. Bruen, the 2022 decision he authored declaring gun laws presumptively unconstitutional unless there is a “proper analogue” from the Founding era. The Bruen opinion acknowledged a historical tradition of prohibiting “dangerous and unusual weapons,” and in Snope, Thomas basically says he was very serious about the “and.” Since “tens of millions of Americans own AR–15s, and the overwhelming majority of them do so for lawful purposes, including self-defense and target shooting,” Thomas says, they aren’t unusual, and can’t be banned.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which decided Snope below, recognized that argument as absurd, noting that it would lead to a constitutional right to a nuclear warhead if they became sufficiently popular. But Thomas brushed the Fourth Circuit’s analysis aside as too impractical to be worth worrying about. “Even if some nuclear warheads are small enough for an individual to carry, no reasonable person would think to use one to defend himself,” said Thomas. “Still less could nuclear warheads ever become a common means of self-defense.”

Although Justice Brett Kavanaugh did not share Thomas’s rush to decide these cases, he published a statement in Snope indicating that he was still on the dissenters’ side. “A denial of certiorari does not mean that the Court agrees with a lower-court decision or that the issue is not worthy of review,” said Kavanaugh. He said he believes there’s a “strong argument” that AR-15s are protected under the Second Amendment, and concluded that the Court “should and presumably will address the AR–15 issue soon, in the next Term or two.” In other words, would-be civilian owners of military-style weapons just need to be a little patient.

Kavanaugh tried to explain his stalling by pointing to lower courts reviewing similar cases, and claiming their opinions will “assist this Court’s ultimate decisionmaking on the AR–15 issue.” But the Court has already weighed in on this “issue”: In 2008, when the conservative justices in District of Columbia v. Heller invented an individual right to gun possession untethered from militia service, Justice Antonin Scalia said that “weapons that are most useful in military service—M-16 rifles and the like—may be banned.” Today, appeals courts remain in universal agreement that semiautomatic weapons bans are constitutional; there is no need for the Court to clarify conflicting lower court interpretations of the same law. Gun activists simply want the Court to declare a constitutional right to AR-15s, too.

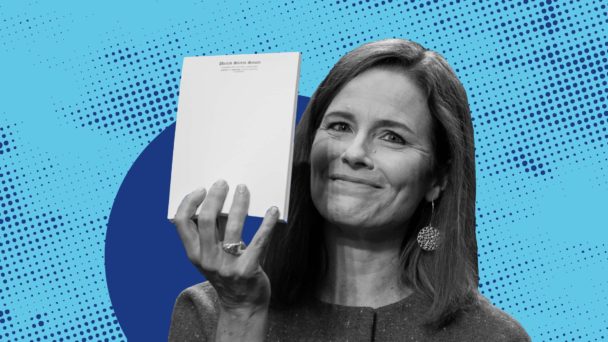

Why, then, does Kavanaugh want to delay? Only four justices need to agree to hear a case, but five justices need to agree to change the law. And for whatever else one can say about Kavanaugh’s intellect, the man does know how to count to five: Kavanaugh, Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch are presumably a man, or woman, short. Denying certiorari now gives Kavanaugh time to pull Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett to their side. Letting cases evolve in the lower courts may make that task easier, since a circuit split would both provide the Court with a more reasonable justification for intervening, and also possibly produce arguments that Roberts or Barrett would find more credible than those that exist now.

Other political calculations may also be at play. Kavanaugh’s waiting game may keep his ideological allies from deciding the case before the midterm elections, inadvertently driving Democrats to the polls in 2026. And say Roberts, age 70, decides to pack up his chambers and go home? Replacing a single justice could be enough to have the necessary five votes to again upend the law.

Thomas’s dissent betrays his impatience to effectuate the Republican Party’s policy agenda. But Kavanaugh’s statement shows he understands how well-positioned the conservative legal movement is in the years to come—and that there is no need to be hasty.