Most pigs, cows, and hens that people in this country eat are born on factory farms to mothers who are confined for the entirety of their lives to metal cages so small that they cannot even lay down. In 2018, California voters tried to do something about this by passing Proposition 12, which prohibits farmers from selling pork, veal, and eggs in California that come from animals “confined in a cruel manner.”

Unsurprisingly, the nation’s producers of pork, veal, and eggs had something to say about this. On Tuesday, they asked the Supreme Court in National Pork Producers Council v. Ross to decide that Proposition 12 unfairly burdens out-of-state farmers in a market that extends well beyond California’s borders.

The Constitution’s Commerce Clause allows Congress to pass laws that regulate commerce “among the several States”—in other words, laws that regulate the national economy. But from this language, the Supreme Court has also inferred what’s known as the Dormant Commerce Clause: the idea that states can only regulate within their own borders, and can’t pass laws that burden other states’ economies or residents. In 2019, for example, the Court struck down a Tennessee law that imposed a two-year residence requirement for state liquor licenses, arguing that the state hadn’t shown a “legitimate local purpose” for the differential treatment.

PIGS (Photo by: Edwin Remsberg/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Ross is about whether Prop 12 passes this test: whether California’s moral objections to the mistreatment of animals is a legitimate local purpose, or whether the law forces too many out-of-state meat producers to change how they operate. At oral argument, lawyers for California asserted that the law only covers what the state’s own residents consume. The National Pork Producers Council countered that the ripple effects from changes to California’s outsized share of the national pork market—13 percent—will inevitably impact the practices of out-of-state farmers.

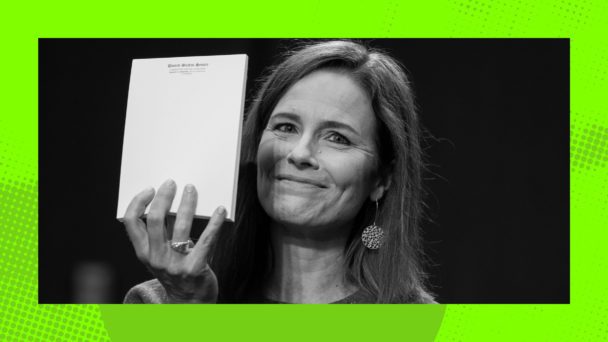

The implications of the Court’s decision in Ross could extend well beyond prices in the butcher shop. Much of the Council’s argument—and the justices’ questions at oral argument—centered on the ramifications of allowing states to regulate out-of-state products produced under conditions with which they disagree. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, for example, asked about hypothetical state laws banning the sale of produce handled by undocumented immigrant workers. Justice Samuel Alito asked if California could ban the import of products made in factories that don’t comply with U.S. environmental laws. Justice Amy Coney Barrett wondered if states could pass laws barring the sale of goods from companies that do not provide employees with adequate healthcare, or that don’t require employees to get vaccines.

No one brought up laws regulating abortion access during oral argument. But they were surely on the justices’ minds: Although the Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, people living in states with abortion bans haven’t stopped accessing abortion care. They travel out of state to obtain it, or order medication from states that do not restrict it. In response, Republican lawmakers have floated bans on out-of-state travel to seek abortion care, which is where Ross comes in. A decision for the pork producers that strengthens the Dormant Commerce Clause could limit the ability of red states to pass more draconian anti-choice laws. A decision for California that weakens it could give red states the green light.

State laws that target abortion care providers have already impacted access to care beyond the enacting state’s borders. In July, for example, Planned Parenthood of Montana temporarily stopped providing abortion pills to out-of-state residents for fear of liability in cases of residents of states that criminalize abortion care providers. If the Court’s ruling in Ross empowers states to pass laws like these, changes to grocery store prices could be just the beginning of the case’s impact.