Every ten years, after each Census, states are charged with redrawing their congressional districts to ensure roughly proportional population counts between them. All of this is done to protect the supposedly fundamental principle of “one person, one vote”—the idea that your voting power in your state shouldn’t depend on where you live within it.

Historically, state legislators were in charge of this process, with virtually no rules to follow about how to do it. As you might expect, members of both parties have long sought to maximize their chances of remaining in power: By “packing” voters of one party into a smaller number of districts and/or “cracking” them across a larger number of them, savvy line-drawers can create maps that look nothing like the preferences of actual voters. In 2016, for example, North Carolina Republicans cashed in on the gerrymandered maps they drew in 2010, winning 10 out of the state’s 13 congressional seats despite winning just 53 percent of the statewide vote. Over the four elections between 2012 and 2018, Maryland Democrats never won more than 65 percent of the statewide vote—but still won 7 out of 8 congressional seats.

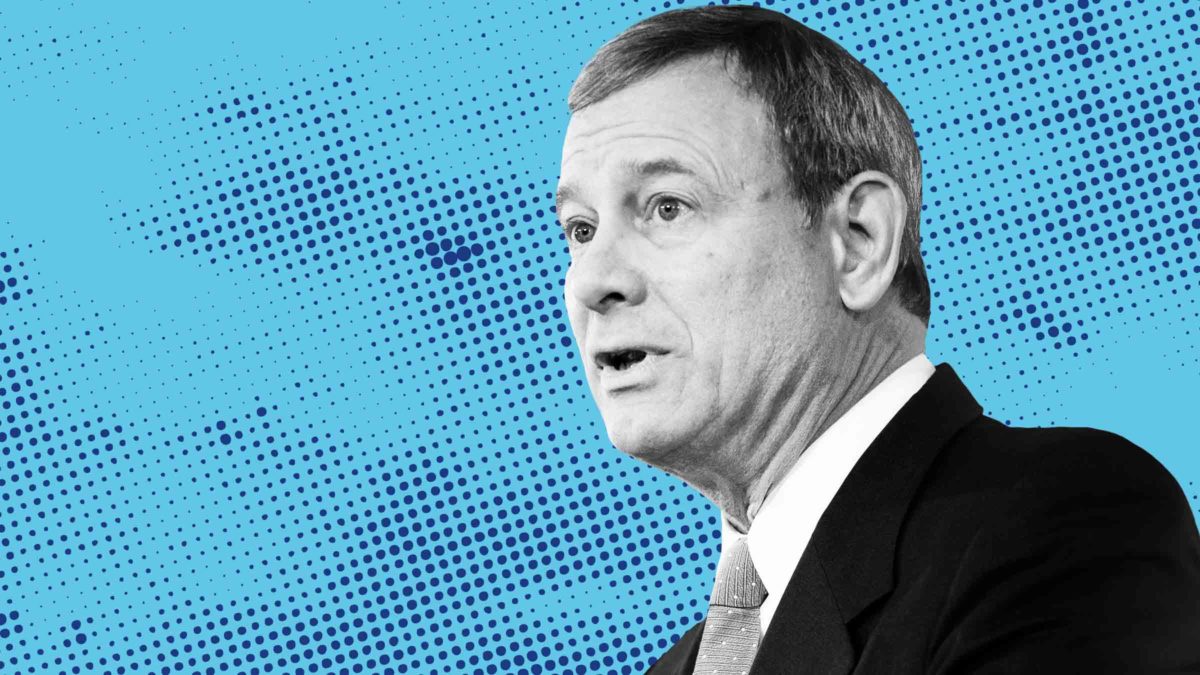

Lawmakers in several states, including North Carolina, Ohio and Wisconsin, have already had their proposed 2020 maps challenged as partisan gerrymanders too extreme to stand for the next decade. Thanks largely to Rucho v. Common Cause—a 2019 U.S. Supreme Court decision in which Chief Justice John Roberts and the conservatives declared that the highest Court isn’t qualified to fix this problem—voters seeking to challenge the maps may be shit out of luck.

Both Democrats and Republicans are guilty of gerrymandering. But in practice, it is a more valuable tool for Republicans than for Democrats: 31 state legislatures are controlled by Republicans, compared to just 18 for Democrats. (Only one state, Minnesota, has a divided legislature.) In the 2020 redistricting cycle, Republicans control the redistricting process in states that are home to 187 congressional seats, compared to just 75 seats for Democrats. Without some kind of check on this process, millions of Democratic voters could spend the next decade being robbed of meaningful representation in their state legislature or Congress.

“I do solemnly swear to enable Republican voter suppression at every opportunity…” (Photo via Getty Images)

Fortunately for Republicans and unfortunately for democracy, the Supreme Court washed its hands of that responsibility two years ago in Rucho. In a 5-4 decision written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Court concluded that the federal judiciary is powerless to prevent lawmakers from drawing boundaries that entrench themselves in office. Because the infallible Framers specifically delegated this task to state lawmakers, Roberts wrote, it must remain there no matter how cynically state lawmakers fulfill it. In a particularly insulting section of the opinion, Roberts expressly disclaimed any official support for partisan gerrymandering, calling it “incompatible with democratic principles,” but encouraged voters dissatisfied with the politicking of their representatives to voice their concerns via the broken political process. This is sort of like telling a tenant with a broken water heater and an absentee slumlord to pick up the phone and try calling again.

Because the Court refused to weigh in on partisan gerrymandering—and, of course, the Republican Party aggressively shuts down legislative efforts to curb it—voters hoping to challenge maps these days are more or less limited to seeking recourse in state courts. And despite Roberts’s insistence to the contrary, Rucho has allowed partisan gerrymandering to thrive. For people who care about living in a representative democracy, their efforts to prevent their elected officials from wrecking it face an uncertain future.

Under an 2020 executive order issued by Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers, a Democrat, a nonpartisan redistricting commission drew maps ostensibly to assist the legislature with the redistricting process. Republicans, however, announced that they would ignore the Commission and submitted their own maps which, shocker, have drawn sharp criticism for being so heavily gerrymandered. Last month, Evers vetoed those GOP-drawn maps, sending the issue to the Wisconsin Supreme Court for a final ruling.

Without some kind of check on partisan gerrymandering, millions of Democratic voters could spend the next decade being robbed of meaningful representation in their state legislature or Congress.

Instead of taking up the question before them, however, the justices claimed to be powerless, writing that “claims of political unfairness in the maps present political questions, not legal ones.” The court, where conservatives hold a 4-3 majority, said it would strive to keep the new maps roughly aligned with the previous ones. Because that 2011 map was itself a brutal gerrymander drawn by the Republican-controlled legislature and approved by a Republican governor, the court’s decision to punt here is effectively a win for the GOP.

The North Carolina state legislature, undeterred by the blizzard of lawsuits brought against its 2010 maps, approved in November a map that would give the GOP an advantage in 10 of the state’s 14 congressional seats; during last year’s presidential election, former President Trump eked out a victory by fewer than two percentage points. Last week, the state supreme court ordered the state’s primaries delayed for two months while the justices consider ongoing legal challenges. The North Carolina GOP huffed and puffed at the prospect of actual judicial scrutiny of their gerrymandered maps, saying in a statement that the court-ordered delay “just injected more chaos and confusion into elections.”

In Ohio, voters overhauled the redistricting process in 2018, passing a constitutional amendment designed to facilitate compromise between the two parties. Although the state’s electorate is split 54-46 between Democrats and Republicans, the GOP-controlled legislature nevertheless put forth an audacious map that would preserve their existing state legislature supermajorities. The Ohio Supreme Court will decide whether the proposed maps pass legal muster; given that Republicans hold a 4-3 majority, the smart betting money is on “yes.”

All this chaos stems from the fact that in deciding Rucho, the Supreme Court left state judges with no guidance for determining if and when partisan gerrymandering veers into unconstitutional territory. Under Roberts’s leadership, the Court has had no qualms about making new rules whenever it doesn’t like the status quo. But with the GOP’s electoral future at stake, the Court, in a gesture of intellectual humility so rare it feels suspicious, decided that this particular task is too difficult for the nine of the nation’s sharpest legal minds. In a country where gerrymandering already heavily favors Republicans, this performance of neutrality simply delivers the GOP more wins.

In Rucho, Roberts claimed that the Court’s conclusion “does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering.” In reality, it did exactly that.