Last year, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, California adopted modest restrictions on indoor gatherings to prevent illness and death. Medical experts hailed the restrictions for saving lives, but churches sued, claiming the temporary ban violated their First Amendment right to hold in-person religious services.

In February, the Supreme Court, by a 6-3 vote along ideological lines, struck down the state’s restrictions, ruling that in-person transmission of a deadly respiratory illness must be allowed to proceed.

It was an audacious ruling in many ways. The Court substituted its own views on a critical scientific matter for those of medical experts, engaging in what Justice Elena Kagan acerbically called “armchair epidemiology.” It held that the law discriminated on the basis of religion, even though it treated religious and non-religious gatherings equally. And six unelected judges decided that they should set pandemic policy, rather than the government voters elected.

That last aspect of the ruling—the Court overturning the decision of elected officials—made it a classic case of “judicial activism.” The Court has been doing a lot of judicial activism these days. Last month, it overturned the Biden administration’s moratorium on evictions enacted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In July, it invalidated California’s requirement that charities reveal the identities of their donors, a decision that could lay the groundwork for gutting disclosure requirements for contributors to political campaigns—long a holy grail for the conservative movement.

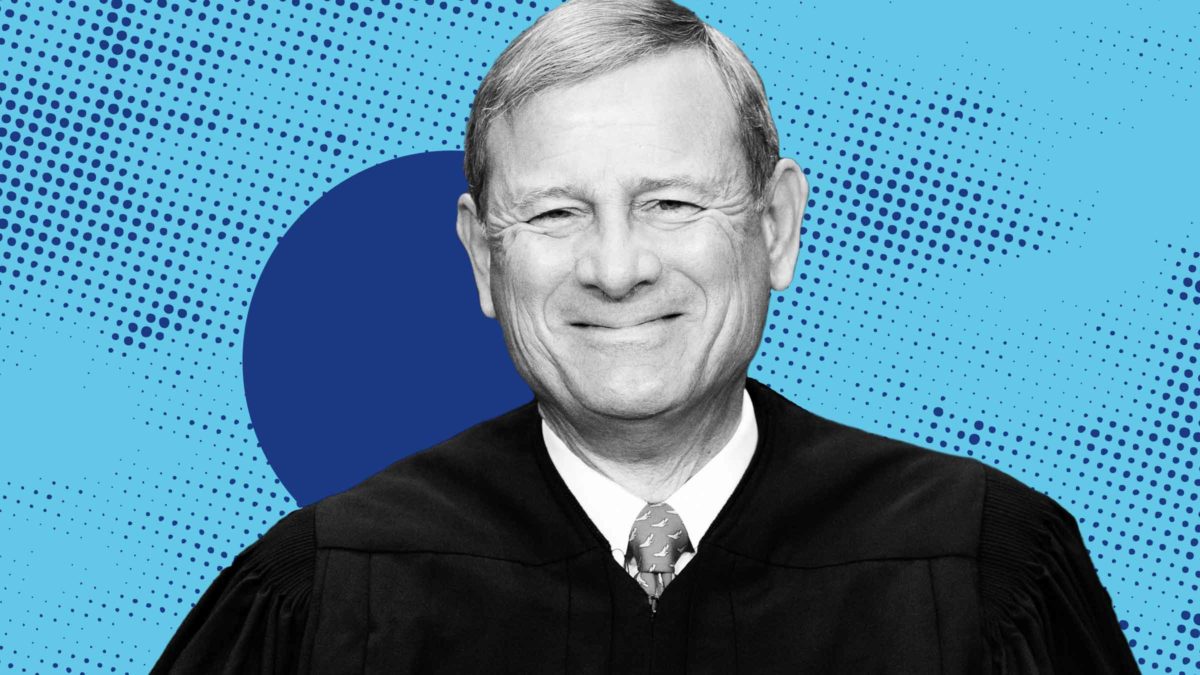

What is striking about all this conservative judicial activism is that it was not supposed to happen—or, to put a finer point on it, we were lied to. Conservatives have long fulminated against “activist” judges, accusing liberals of being “politicians in robes” who enact policies through judicial decree that would not be adopted by the political branches. Chief Justice John Roberts became one of the most prominent proponents of this view when he famously declared, at his Senate confirmation hearing in 2005, that “judges are like umpires. Umpires don’t make the rules; they apply them.”

Although Roberts’ statement has become an iconic expression of the anti-activist perspective, conservatives’ professed allegiance to judicial restraint goes back far earlier. During the Warren Court in the 1960s, conservatives decried the liberal majority’s “judicial usurpation of legislative functions.” In response to that Court’s unprecedented expansions of civil rights, especially for nonwhite Americans, criminal defendants, and other members of marginalized communities, some conservatives—led, infamously, by the far-right John Birch Society—called for Chief Justice Earl Warren’s impeachment. Richard Nixon campaigned for president in 1968 on a vow to rein in the Court, and the 1972 Republican Party platform touted his administration’s record of appointing judges with “fidelity to the Constitution.”

Conservatives continued spouting the anti-activist line, but a funny thing happened as the Court developed a strong conservative majority: It began a new era of right-wing judicial activism. Under Chief Justice William Rehnquist, it went on a federalism crusade, invalidating key parts of the Violence Against Women Act and the Gun-Free School Zones Act for ostensibly exceeding the powers of Congress. Rehnquist and his fellow conservatives, who had pledged allegiance to states’ rights and an antipathy for liberal policies coming from Washington, suddenly used novel interpretations of the Constitution to aggressively rein in the federal government.

The Roberts Court has been even more enthusiastic in its right-wing judicial activism. In Citizens United v. FEC, it used an expansive and dubious reading of the First Amendment to strike down a major congressional enactment that prohibited corporations from spending money to support or oppose candidates for elected office. In Parents Involved v. Seattle School District No. 1, the Court, which had already turned sharply against court-ordered desegregation plans, now insisted that even voluntary integration plans could be unconstitutional because they discriminated against white students. And in Shelby County v. Holder, the Court struck down the Voting Rights Act’s “preclearance” regime, which required states and localities to get approval from the Justice Department or a federal court to enact changes in voting rules that could make it harder for racial minorities to vote. In so doing, the Court relied on a made-up constitutional doctrine—something it called “equal sovereignty” of the states—that even Richard Posner, a conservative federal appeals court judge nominated by Ronald Reagan, said does not exist. The Court’s decision, Posner wrote, “rests on air.”

The Supreme Court should be the champion of the least powerful members of society. The conservative activists on today’s Court are wielding judicial activism on behalf of those who need it least.

It might be argued that even if conservative justices are “activists,” that is no worse than when the Warren Court’s liberal majority did the same. That is wrong. For one thing, the Warren Court was engaging in activism on behalf of groups—racial minorities, poor people, criminal defendants—that traditionally have had difficulty protecting their rights through the elected branches. The conservative justices, by contrast, have been activists for corporations, white students opposed to integration, and, in its ruling last month striking down the Biden administration’s eviction moratorium, wealthy landlords. The Supreme Court should be the champion of the least powerful members of society, whose rights are most in danger. The conservative activists on today’s Court have reversed this principle, and are instead wielding judicial activism on behalf of those who need it least.

More fundamentally, what is so galling about the Court’s conservative judicial activism is the dishonesty behind it. Liberals are generally upfront about their belief that courts should not shy away from “activist” rulings necessary to protect marginalized Americans. Conservatives, however, have long insisted that they believe in judicial restraint, and in some cases, including Roberts’s, they have promised the Senate they would not engage in activism if they were confirmed.

There is every reason to believe the newly enlarged conservative majority is about to become even more activist. For the last two decades, the legal basis for affirmative action has been hanging by a thread; now, there is a good chance that the Court will strike a major blow against affirmative action next year in a high-profile challenge to Harvard’s admission policies, using a radical new interpretation of a major federal civil rights law that would make it far more difficult for universities to consider race, including the value of racial diversity, in its admissions decisions.

Critics of the conservative justices may not be able to stop this Court from engaging in judicial activism, but they should at least call out the hollow nature of the charge. Roberts has never been the umpire he claimed to the Senate to be. He and the conservatives are wielding the law as a bat and swinging for the bleachers.