On Thursday, the Supreme Court uncorked its latest exercise of raw political power disguised as anodyne legalese, to the detriment of everyone who enjoys the idea of spending an afternoon on the lake without worrying if the water is slowly poisoning them. In Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency, Justice Samuel Alito, writing for five conservative justices, spent close to 30 pages noodling over what, exactly, the word “waters” means. (Not “water,” mind you. Waters.) Naturally, he eventually landed on an interpretation that could facilitate the destruction of a decent-sized chunk of the environment.

The Clean Water Act is a 1972 federal law designed to protect the “waters of the United States.” The Environmental Protection Agency, an executive agency charged with enforcing the Act, defines “waters of the United States” as those waters that “could affect interstate or foreign commerce,” along with “wetlands adjacent” to those waters. The statutory text is, admittedly, a little muddled, but the Clean Water Act is one of the federal government’s most successful environmental laws, and prevents cities and businesses from dumping hundreds of billions of chemical waste, raw sewage, and other pollutants into streams, lakes, and oceans every year.

Enter the Sacketts, an Idaho couple who bought land on which to build their dream home overlooking Priest Lake. (Also, enter their lawyers at the Pacific Legal Foundation, a conservative “public interest” law firm that looks for people like the Sacketts with cases that could advance PLF’s policy agenda.) The Sacketts’ dream apparently required backfilling the wetlands on their property—wetlands separated from the lake by a road, but that were once part of a larger body of wetlands. (Yes, it’s a little on the nose that these nature lovers wanted to wreck one body of water to build a house overlooking another.) The presence of these wetlands implicated the Clean Water Act, which imposes civil and criminal penalties on people who violate it.

The Sacketts had several options available as they planned out construction of their home. They could have gotten a jurisdictional decision from the Army Corps of Engineers as to whether the wetlands were covered under the Clean Water Act. They could have applied for a federal permit. But those things cost money and time, something that Sam Alito does not believe they need to spend. So they sued, challenging the EPA’s designation of the wetlands near their home as, well, wetlands.

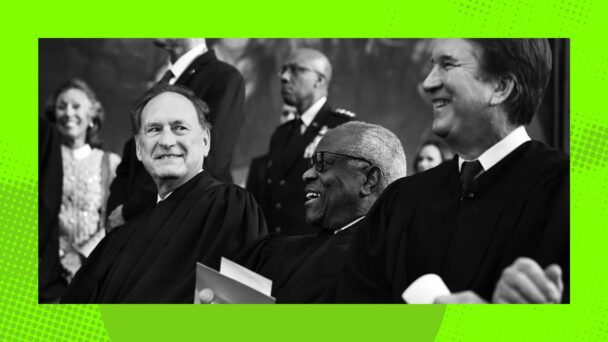

(Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images for Protect our Waters)

The Court’s judgment in Sackett is unanimous—every justice agreed that in this particular case, as to the Sackett family home, the Clean Water Act does not apply. Where they disagree, however, is how much further than that the Court should go. The liberal justices, along with Justice Brett Kavanaugh, would leave the matter there. But Alito and the other conservatives took it upon themselves to dispose of the EPA’s existing wetlands rules and substitute their own, swapping out the judgment of scientists and engineers and other actual experts for the judgment of the four former Federalist Society chapter presidents who are now serving as Alito clerks.

The government had argued that “waters” encompasses wetlands because “the presence of water is universally regarded as the most basic feature of wetlands.” For Alito, however, this Zoolander-esque construction does not track. “Consider puddles, which are also defined as the ordinary presence of water,” he writes; the implication seems to be that he must stop the EPA from regulating every inch of ground every time it rains. Never mind that Alito’s own opinion, a mere six pages earlier, quotes the EPA regulation that specifically excluded puddles and swimming pools from the definition of “waters.” By portraying ERA scientists as zealots who want to regulate your bathtub, Alito can pare back environmental protections until they’re so small that they could, in the words of anti-government goon Grover Norquist, be drowned in one.

By holding that wetlands are only covered by the Clean Water Act if they have a “continuous surface connection” to “waters of the United States,” the Sacketts won their case after some two decades in federal court. The real winners, though, are the nation’s industrial-strength polluters, because this ruling removes about half of wetlands in the United States from the protections of the Act. Also thrilled? Oil and gas companies, who supported the Sacketts’ position and will no longer have to navigate quite as much red tape before beginning their latest multibillion-dollar fracking project.

Kavanaugh wrote a concurrence in the judgment only, expressing concern about the “real-world consequences” of the majority’s overreach. But it is Justice Elena Kagan’s separate concurrence, joined by Justices Sotomayor and Jackson, that called out the majority for this giveaway to corporations. When Congress passed the Clean Water Act, she writes, drinking water was hazardous sludge, fish were pumped full of poison, and rivers were literally bursting into flames. Things are much better now precisely because the Act works as Congress intended.

But, says Kagan, the majority decided that “it must rescue property owners from Congress’s too-ambitious program of pollution control.” To get there, she pointed out that Alito had to ignore what Congress wanted and instead create a new rule—that if Congress wanted to regulate private property, it has to use “exceedingly clear language.” Never mind that the entire point of the Act, as Kagan said, is to “stop property owners from polluting.” To the majority, preventing the nation’s groundwater from consisting mostly of mercury is not worth the burden associated with having to obtain building permits.

Read side by side, Alito and Kagan’s opinions display radically different approaches to the law, and not just because Alito so clearly wanted to make sure property owners don’t have to follow rules they don’t like. Alito’s opinion is the sort of ahistorical faux-textualism that lays bare the power of the methodology’s selective deployment, parsing words like “waters” and “adjacent” in ways that are utterly unmoored from how the real world works.

Kagan concludes by cribbing her own language from her dissent in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, a case from just last term in which the Court gutted a different environmental statute—the Clean Air Act. This time, Kagan needed to change only one word of her analysis: “The Court substitutes its own ideas about policymaking for Congress’s. The Court will not allow the Clean [Water] Act to work as Congress instructed,” she wrote. “The Court, rather than Congress, will decide how much regulation is too much.” Given the conservative justices’ rabid hostility to all things regulatory, Kagan will likely be able to recycle this language a few more times in her career.