Nebraska, along with five other states led by Republican attorneys general, are suing President Joe Biden to stop him from forgiving billions of dollars in student loan debt. The Supreme Court will hear oral argument in the case, Biden v. Nebraska, on Tuesday. How the justices resolve the case could change the lives of some 43 million eligible borrowers who are still waiting to find out whether the Court is going to let Biden govern or not.

If decisions about nationwide student loan relief sound like they should be above any one state’s pay grade, you’re not alone in thinking so. But Nebraska, along with Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and South Carolina, has invoked a judge-made rule called the major questions doctrine to argue that courts must stop Biden from attempting to address the student debt crisis. The doctrine allows judges to invalidate agency actions if they decide Congress didn’t speak clearly enough when delegating authority over issues of great “economic and political significance”—so, “major” questions—to the executive branch. By canceling student debt, the state writes in its brief, the Biden administration “claims breathtaking and transformative power beyond [its] institutional role and expertise.”

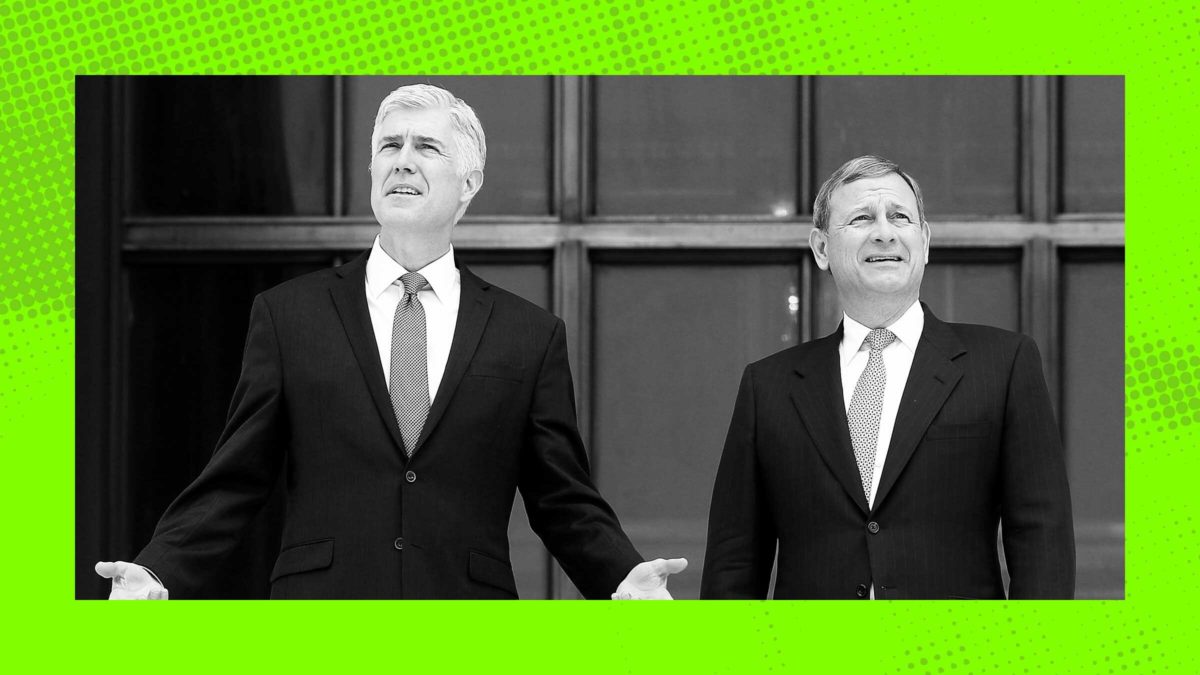

This isn’t the first time states have used the doctrine to urge judges to strike down laws they don’t like. Last year, West Virginia successfully challenged the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate carbon dioxide emissions under the Clean Air Act; writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts explained that the concept reins in “agencies asserting highly consequential power beyond what Congress could reasonably be understood to have granted.” Nebraska’s brief in the student debt case also cites the Court’s invalidations of the Centers for Disease Control’s eviction moratorium and the Department of Labor’s vaccine-or-test rule, making sure to place its argument in the context of other recent major questions cases. By playing into the justices’ naked power grab, these states are working to transform the crushing debt burden of a generation into a tax win and budget bump.

On the campaign trail in 2020, Biden pledged to eliminate undergraduate student debt for borrowers making up to $125,000 per year, and to forgive $10,000 worth of debt to help those struggling to make ends meet during the COVID-19 pandemic. Last fall, the White House revealed plans to make good on this promise, relying on its authority under the HEROES Act, a 2003 law that allows the Secretary of Education to waive or modify any law that applies to “student financial assistance programs” during a national emergency—like, say, COVID-19.

But according to Nebraska, Congress could not have intended to grant the president this sweeping power, because lawmakers “conspicuously and repeatedly declined to enact many student-loan discharge bills” in recent years. The states also claim to suffer a “direct injury in the form of a loss of specific tax revenues”: In its 2021 pandemic relief legislation, Congress declared that debt forgiven between 2021 and 2025 would be excluded from federal adjusted gross income. Because these states calculate state taxable income based on their residents’ federal adjusted gross income, they say the Biden administration is cutting into their bottom lines. Given the twelve-figure price tag associated with student debt relief, they conclude, the Court has a duty to weigh in on this “major question.”

Nebraska also argues that the HEROES Act’s purpose is to “keep certain borrowers from falling into a worse position financially,” and that Biden’s attempt to put “tens of millions of borrowers in a better position by cancelling their loans en masse” goes beyond his authority. In making this argument, Nebraska ignores the evidence cited by the administration that the $125,000 income threshold targets relief at the most vulnerable borrowers—those who are “disproportionately likely to become unemployed and experience material hardship due to the pandemic.” According to the government, “without relief, lower-income borrowers were likely to experience increased default and delinquency rates beyond pre-pandemic levels.”

Especially since the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett in 2020, Republican state attorneys general have carved out an outsized role in setting federal policy, urging the Court’s conservatives to throw wrench after wrench into the Biden administration’s ability to implement its agenda. A ruling in Nebraska’s favor would encourage even more ambitious invocations of the major questions doctrine to strike down progressive policies. As long as states can convince Roberts and company that such policies are too economically significant to be legal, the Court will continue to be the center of Republican political power.