On Saturday, Terence Andrus died by suicide in a state prison in Livingston, Texas. He was 34 years old. If the U.S. Supreme Court had taken seriously its obligation to protect his constitutional rights, Terence might still be alive today.

In 2004, police arrested Terence, then 16, for serving as a lookout while his two friends robbed a woman of her purse. The judge sent him to a juvenile detention center in Fort Bend County in the custody of the Texas Youth Commission (“TYC”), the state’s juvenile corrections agency, for a year and a half.

The facility was a nightmare. Terence lived in an overcrowded unit where the only medical personnel was a “semi-retired medical doctor,” who frequently used “medical restraints,” including high doses of psychotropic drugs, to keep things under control. Staff placed Terence in solitary confinement 77 times; sometimes as punishment for minor rules violations, and sometimes at his request, to avoid violence associated with the facility’s “brutal pecking order.” According to Terence, because the walls were often covered with semen, he had to wrap toilet paper around his feet to stay clear of it.

Terence Andrus died by suicide on death row in Texas this past Saturday. His death sentence should have been overturned but the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ignored the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion. Terence had a long history of serious, largely unaddressed mental illness. pic.twitter.com/QjiLvIyonp

— Sister Helen Prejean (@helenprejean) January 24, 2023

Terence, who spent his last 90 days in juvenile custody in solitary confinement, was sent to adult prison when he turned 18. Later, a state ombudsman who investigated TYC would later testify on Terence’s behalf that the time he spent in solitary confinement “would horrify most current professionals in our justice field today.”

Soon after his release from prison, Terence, then 20, shot and killed two people outside of a Fort Bend Kroger while high on PCP-laced marijuana. While in jail awaiting trial, he slashed his wrists and used his blood to write “just let him die” on the wall of his cell.

In 2012, a jury sentenced Terence to death. But they did so without knowing about Terence’s time in juvie, or his severe mental health issues that dated back to elementary school, when he was first diagnosed with affective psychosis, a mood disorder that causes hallucinations. They also didn’t hear about his mother, who, addicted to drugs, would abandon her five children for days or even weeks at a time. The jury had no idea that Terence was basically forced to become his siblings’ caregiver as a 12-year-old boy.

The jury knew none of this because Terence’s court-appointed lawyer, James Crowley, a former prosecutor for Fort Bend and Harris County, didn’t bother to find any of this out. (Crawley’s name was pulled from a list of defense lawyers in Fort Bend County who can take on cases for people who can’t afford representation on their own.) But by the time Terence’s case landed on Crowley’s desk, a Texas state court had already taken him off of a different death penalty case for constitutionally defective lawyering, and even threatened to criminally charge him with contempt “for substantially interfering with the administration of justice.”

You might think that a track record of failing to represent indigent people would be cause for taking someone off of the indigent defense list, but Crowley stayed under the judicial radar and continued his spate of incompetence. According to Terence’s post-conviction lawyers, during the four years between his appointment and Terence’s trial, Crowley did “almost nothing related to either guilt or punishment” and only met with him six times. He didn’t investigate Terence’s traumatic childhood or his history with chronic mental illness, which he dismissed as “a lot of psychological gobbledygook.” He didn’t call any experts to testify about conditions at Texas’s youth prison facilities or about the origins of Terence’s substance abuse. A federal district court would eventually agree with Terence, finding that his lawyer had “fail[ed] to investigate and present mitigating evidence regarding [Terence’s] abusive and neglectful childhood.”

Terence twice appealed his death sentence to the Supreme Court on the basis that he’d received ineffective assistance of counsel. The first time, in June 2020, a majority of the Court agreed that his lawyer’s performance was an “unconstitutional abnegation of prevailing professional norms,” and sent the case back to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals for further review.

That state court, however, came to the same conclusion in a 2021 opinion, denying Terence a new trial. The Court of Criminal Appeals judges seemed to take offense at the Supreme Court’s order to revisit their decision, writing that they “reiterate—and to the extent or holding was not clear, clarify”—that they had already decided that Terence’s lawyer met constitutional standards. The majority disagreed with the justices about the import of the mitigating evidence that Terence’s lawyer had failed to present, finding it was “relatively weak” and it didn’t significantly impact the outcome.

Three judges dissented, stating that even though they “shared” their fellow judges’ “frustration” with the Supreme Court’s analysis, they had a duty to comply with it. “This Court is not free to ‘re-characterize’ that evidence contrary to the United States Supreme Court’s holding,” they wrote. Terence appealed back to the U.S. Supreme Court.

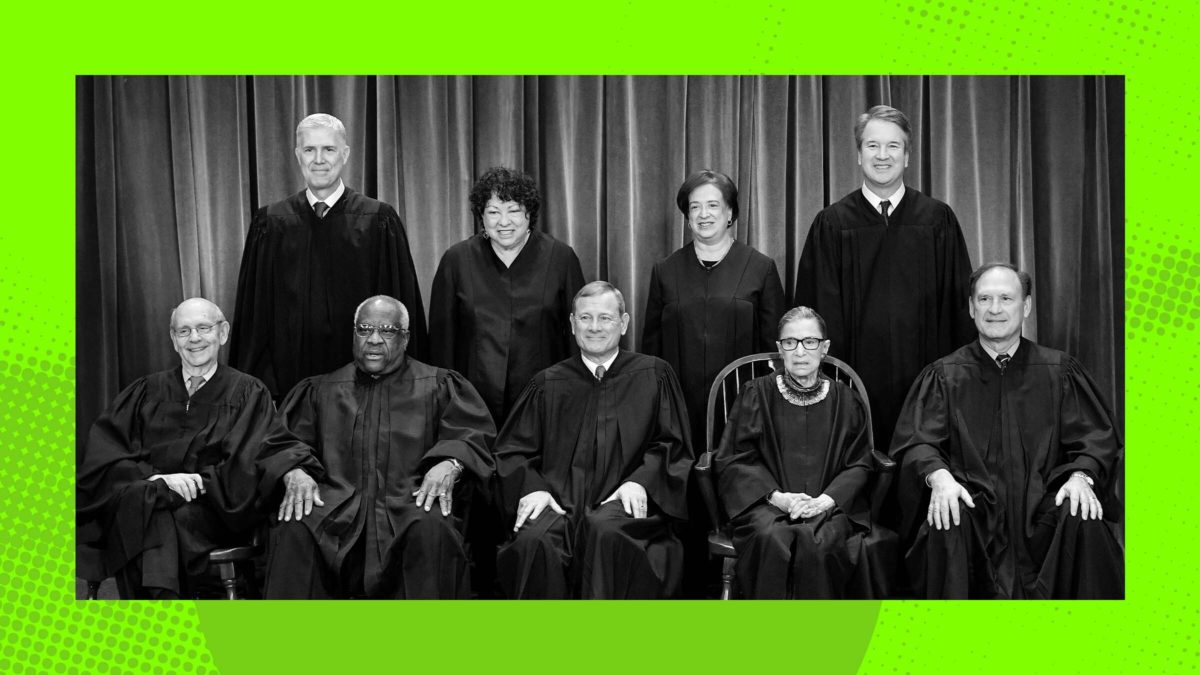

This time, the justices turned him away. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan, dissented. “Andrus’ case cries out for intervention, and it is particularly vital that this Court act when necessary to protect against defiance of its precedents,” she wrote.

“He’d been careening toward the abyss,” since finding out SCOTUS denied him in June, his lawyer – Gretchen Sween – told me.

“He was broken.” pic.twitter.com/hUgZkOmGVJ

— Keri Blakinger (@keribla) January 22, 2023

This past Saturday, Terence died by suicide. His attorney, Gretchen Sween, told Los Angeles Times reporter Keri Blakinger that Terence had been “careening toward the abyss” since the Supreme Court denied his petition.

From the trauma of juvenile detention, to the incompetence of his court-appointed lawyers, to the indifference of the Supreme Court to his rights or his fate, the state failed Terence Andrus. His siblings described him as a “protective older brother” who, at age 12, cooked, cleaned, got them ready for school, and helped them with their homework each night. He kept on them to stay out of trouble. They remembered him as a “very caring and very loving” person, who “never liked to see people cry.”