Just a few minutes into oral argument in Trump v. Colorado last month, it was apparent that the Supreme Court had no intention of enforcing the Disqualification Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to keep Donald Trump off the 2024 presidential ballot. The only real question was about which legal theory the justices would deploy to ensure that Trump, the first U.S. president to foment a deadly insurrection against the government he led, would not face any consequences for his actions.

On Monday, the Court delivered its answer in a sparse opinion designated as per curiam, which means that its conclusions are attributable to the Court, rather than to any one justice or collection of justices. Under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Anderson opinion states, states lack the power to bar candidates from holding federal office. It helpfully notes that Colorado could bar Trump from running for state office, if for some reason he felt like buying a weed shop in Aspen and launching a bid for a seat on the University of Colorado Board of Regents. But because allowing states to use the Disqualification Clause to exclude presidential candidates from their ballots could yield inconsistent results in elections of national importance, the Court concludes, the law mustn’t allow states to go any further.

“An evolving electoral map could dramatically change the behavior of voters, parties, and States across the country, in different ways and at different times,” the unnamed author, whom I would wager one hundred American dollars is Chief Justice John Roberts, writes. “Nothing in the Constitution requires that we endure such chaos—arriving at any time or different times, up to and perhaps beyond the Inauguration.”

The opinion in Anderson does not discount the theoretical possibility of enforcing Section 3 against someone, sometime. But it takes care to ensure that, practically speaking, it will probably never happen to anyone. Section 3, the Court concludes, is not “self-executing”; instead, Congress must pass a law in order to give it effect. This functionally puts Trump beyond the reach of the Disqualification Clause: Because Congress is safely in Republican hands, and Senate Democrats remain more afraid of the hypothetical consequences of spiking the filibuster than they are of the real-world consequences of failing to do so, he can run for president knowing that the people who are supposed to protect democracy from budding despots instead wrote him an insurrectionist hall pass. (The opinion also warns that any such law would “of course” be subject to judicial review, making clear that even if Congress were to pass a law applying the Disqualification Clause to Trump, the justices reserve the opportunity to stuff that law in the garbage.)

Though the outcome in Anderson was a foregone conclusion, it remained to be seen how much incredulous dissent it would elicit. The answer, unfortunately, is basically none. After including a few turns of phrase that are recognizable as barbs only by appellate lawyers with an unfortunate affinity for Supreme Court palace intrigue, even the liberal justices, for some godforsaken reason, agreed to help write part of the Constitution out of existence.

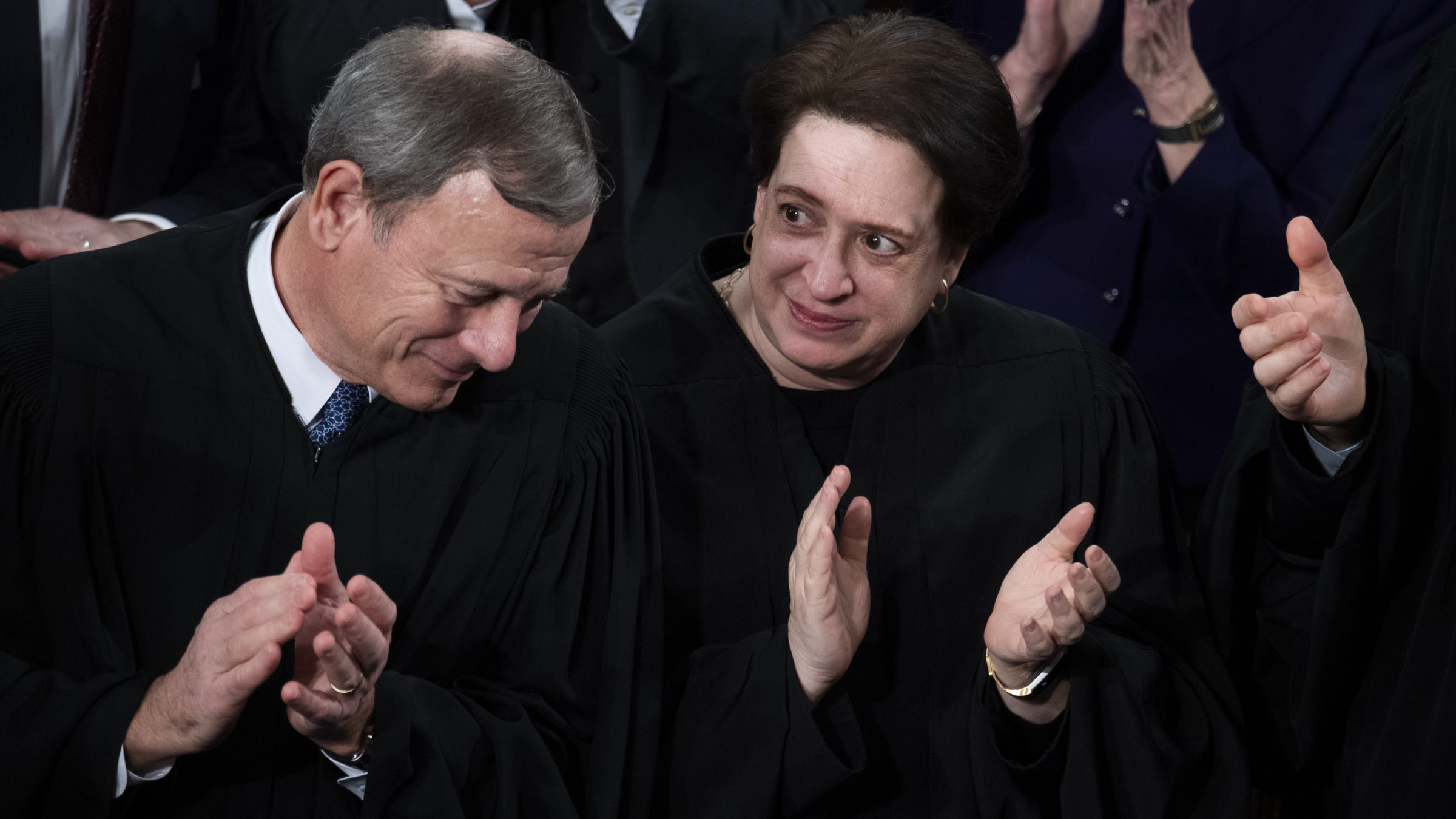

(Photo by Melina Mara/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

In a separate opinion, Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson agreed with the Court’s conclusion that Colorado cannot unilaterally disqualify Trump from the ballot. Yet this, they say, would be enough to resolve the case, without any need for the majority’s sweeping conclusions about the necessity of special congressional action to punish (or not punish) future coup attempters. Quoting Roberts’s maxim in Dobbs that “if it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case, then it is necessary not to decide more,” the liberals accuse the Court of “depart[ing] from that vital principle” to “decide novel constitutional questions to insulate this Court and petitioner from future controversy.” This is the closest they get to stating what is plainly going on: Five Republican justices are taking every precaution necessary to maximize the presumptive Republican nominee’s odds at taking the White House in eight months.

The liberals would be correct to characterize their colleagues as breathtakingly full of shit, and their opinion reads for all the world like, at the very least, a partial dissent: Throughout, it refers to the nominally per curiam decision as a “majority” written by “five justices,” rhetorical conventions that sort of belie the notion that there is full agreement here. Yet for some reason, the liberals style their opinion only as a “concurrence in the judgment,” thus preserving the formal unanimity of Donald Trump’s de facto exoneration.

For anyone who hopes for more from the liberal justices than occasional clapping hand-emoji zingers, this choice is as disappointing as it is baffling, especially since there is evidence that they considered doing things differently. As Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern observed, the metadata of the PDF posted on the Court’s website suggests that at one point, their opinion was a partial dissent, and written by Sotomayor alone. Sometime after when she circulated a draft among her colleagues and before Monday morning, the two other liberals signed on, and the three of them, for reasons we will not know until Joan Biskupic publishes her next dishy Supreme Court book, elected to toe the line. (If you are reading this on your law firm computer, remember this lesson next time your email client reminds you to scrub metadata before sending attached files to opposing counsel.)

Photo By Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

In a partial concurrence, Justice Amy Coney Barrett echoed the liberals’ argument that the Court’s per-curiam-but-not opinion goes further than it needs to, and correctly notes that ordinarily, the “majority’s choice of a different path” would be grounds for a dissent. But not so this time, she says, because “writings on the Court should turn the national temperature down, not up” during “the volatile season of a Presidential election,” which, she scolds, is “not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency.” This awkward conclusion braids Barrett’s partisan preferences with the performative collegiality that permeates the legal profession: On the one hand, the opinion protecting the president who appointed me to the Supreme Court is wrong. On the other, I am too much of a coward to say anything more about it.

If the liberals had set out to deliver headlines that made the Supreme Court look the best and John Roberts feel the happiest, I am not sure what they would have done differently.

For the most part, I think the legal reasoning of dissents is worth the digital paper dissents are printed on. But in a case like this one, the choice of labels matters for reasons that go beyond whatever indignant rhetoric a dissenting justice can muster, and beyond the bare question of who wins and who loses. There is a world in which the justices who disagreed with parts of the primary Anderson opinion exercised their voting power to make the outcome 6-3 or even 5-4—if not changing the outcome, then at least laying bare the extent to which this Court is in the tank for the guy who appointed a third of its membership. Instead, press coverage characterized the decision as “unanimous,” or “9-0”—or, when the candidate himself learned of his blowout victory, both. “Today’s decision, especially the fact that it was unanimous, 9-0, is both unifying and inspirational for the people of the United States of America,” Trump said.

This is obviously a rough time to be a liberal justice, whose two principal tasks are chronicling the accelerating erosion of American democracy and writing somber obituaries for the civil rights they are unable to save. I get that this is thankless work, but that does not obviate the obligation to do it. By repackaging a (partial) dissent as something less, Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson simultaneously handed Trump the result he needed and allowed the Republican justices to frame the Court as unified in its principled defense of representative democracy. If the liberals had set out to deliver headlines that made the Supreme Court look the best and John Roberts feel the happiest, I am not sure what they would have done differently.

The collection of opinions in Anderson is the work product of a Court whose members are clearly aware that their reputations are in the toilet. The assertion with which Barrett wraps her opinion—that the justices’ differences are “far less important” than their putative unanimity, which “is the message Americans should take home”—reads less like legal analysis than a maudlin plea from a justice who knows exactly how little credibility the institution has left. Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson could have pressed this argument, exposing the Court as a rubber stamp for the Republican Party. Instead, they chose to run cover for it.