On Monday night, the Republican men on the Supreme Court voted to lift a lower court order that had temporarily blocked the Trump administration from summarily shipping Venezuelan migrants to a notorious prison labor camp in El Salvador. The five-justice majority did not sign its decision in Trump v. JGG, styling it instead as a per curiam opinion, which would suggest unanimity if not for the four women justices in dissent.

The unusual appeal arises from the government’s mad dash to implement a proclamation Donald Trump issued in mid-March invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a rarely-used law permitting the detention and removal of citizens of a hostile, invading government during wartime. The proclamation orders the immediate apprehension, detention, and removal of any Venezuelan aged 14 and up who doesn’t have U.S. citizenship or a Green Card and who the government alleges is a member of Tren de Aragua, a transnational gang Trump says is actively invading and at war with the United States.

Legally speaking, this is a crock of shit. A gang is not a government, nor is TdA “invading” the United States. The constitutional authority to declare war lies with Congress, and Congress has not formally done so since World War II. Not coincidentally, that was also the last time the government invoked the Alien Enemies Act, which it used to herd Japanese Americans into camps. This ignominious precedent should be relegated to the dustbin of history. The Trump administration is dusting it off instead.

Within hours of the proclamation’s issuance, hundreds of innocent people were put on late-night flights to El Salvador’s infamous Terrorism Confinement Center, or CECOT. Some detainees with access to a lawyer immediately filed a lawsuit on behalf of everyone subject to the proclamation. And the D.C. District Court quickly granted emergency relief, ordering the government not to summarily remove anyone under the AEA for 14 days. But the government kept renditioning people anyway, and so the district court scheduled a hearing for Tuesday about whether to hold the government in contempt. After the Supreme Court issued its decision Monday, the hearing got called off.

In addition to letting the Trump administration resume its human trafficking scheme, the male justices of the Supreme Court cut off detained migrants’ attempt to fight for their rights together in a class action lawsuit. Instead, they held, the Venezuelan migrants’ only recourse is filing habeas petitions in whatever district they find themselves confined. Some of the detainees “are confined in Texas, so venue is improper in the District of Columbia,” the five Republican men explained; they did not address what other migrants should do if, as here, the “district” they’re detained in is a shithole of a prison cell in a foreign country thousands of miles from home.

For the people whom the government already shipped to CECOT—and people it may ship to CECOT in the future—this is disastrous. Relying on habeas alone generally leaves it up to detainees to navigate the legal system by themselves or try to find their own lawyers—who have to find out where detainees even are—and just hope for timely relief.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem signs the agreement with the Salvadoran government to ship detainees to CECOT (Photo by Alex Brandon-Pool/Getty Images)

The Supreme Court’s decision also gives the government an incentive to stash detainees near friendly right-wing judges before kicking them out of the country, again making it harder for migrants to meaningfully challenge their removal to a nightmarish facility abroad. Attorney General Pam Bondi acknowledged as much in a Fox News interview on Tuesday, promising that hearings would be “smoother,” “simpler,” and “much faster” going forward. Trump v. JGG thus confirms that migrants have a constitutional right to due process, in theory, but makes it much harder to access that right in practice.

Unlike Republicans in the White House, who are publicly relishing the harm they are inflicting on immigrants, Republicans on the Supreme Court made a concerted effort in Trump v. JGG to distance themselves from the facts on the ground and the consequences of their actions. The majority sidesteps the absurdity of Trump’s claim that the Alien Enemies Act empowers him to haphazardly remove any Venezuelan he alleges is in a gang, simply saying, “We do not reach those arguments.” The majority similarly skips over the government’s attempt to evade judicial review by hurrying migrants onto secret midnight flights, and its argument that it has no obligation to retrieve anyone it exiles by mistake. The majority doesn’t even mention the words “El Salvador” in its opinion, which, in a decision allowing the mass removal of American residents to an Salvadoran jail, feels like an embarrassing oversight.

In a dissent joined in full by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, Justice Sonia Sotomayor painstakingly lays out how and why “the Government’s conduct in this litigation poses an extraordinary threat to the rule of law,” and characterizes the majority’s rewarding of that behavior as “indefensible.” Sotomayor points out that a Salvadoran official “boasted” that people held in the prison “will never leave,” and cited evidence that detainees at CECOT are “rarely allowed to leave their cells, have no regular access to drinking water or adequate food, sleep standing up because of overcrowding, and are held in cells where they do not see sunlight for days.” Without the dissent, anyone reading the opinion would have no concept of the peril into which the Court has plunged these people, to say nothing of the Constitution’s protections.

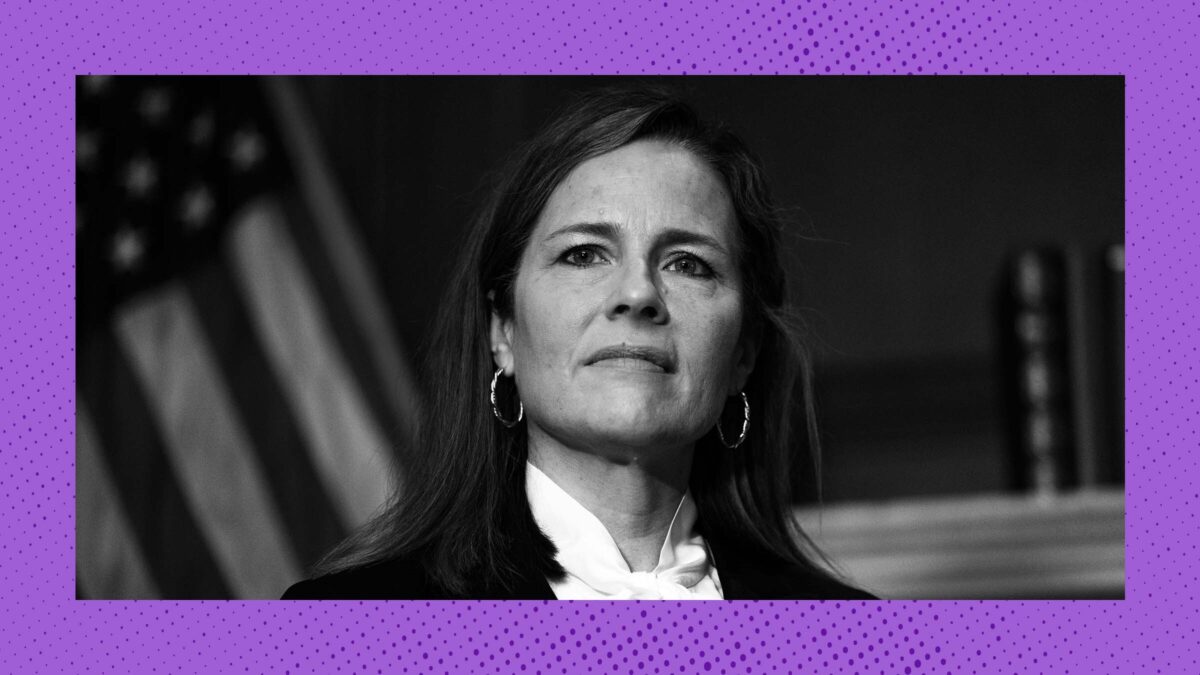

Justice Amy Coney Barrett dissented, too, but only in part: She joined Part II of Sotomayor’s opinion, which discusses the agreement of all nine justices that detainees have a constitutional right to due process (at least in theory), and Part III-B, where Sotomayor discusses the baselessness of the majority’s conclusion that habeas petitions are the exclusive way the detained migrants can resolve their claims. But she studiously avoided joining every part of Sotomayor’s dissent that acknowledges what is actually happening, that it is illegal, and that it is immoral. The Democratic justices said that “funneling plaintiffs’ claims into individual habeas actions across the nation risks exposing them to severe and irreparable harm.” Barrett did not. The Democratic justices admonished the majority for intervening “without accounting” for the myriad ways throughout this case that “the government has largely ignored its obligations to the rule of law.” Barrett did not.

The Democratic justices warned that the clear implication of the government’s position is that “not only noncitizens but also United States citizens could be taken off the streets, forced onto planes, and confined to foreign prisons with no opportunity for redress if judicial review is denied unlawfully before removal.” Barrett did not. She took the liberals’ side only insofar as she agrees that detainees have rights, and that the majority didn’t provide evidence for its conclusion that there is only one way to protect those rights. Otherwise, she agrees with her conservative colleagues on a more fundamental principle: They are happy to facilitate suffering. They just don’t like to talk about it.