Earlier today, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Garland v. VanDerStok, the justices’ latest opportunity to threaten the elected branches’ ability to address the national gun violence crisis. Congress passed the Gun Control Act of 1968 to regulate “the business of importing, manufacturing, or dealing in firearms” with requirements like background checks for gun purchasers and serial numbers on the guns themselves. But some manufacturers have been skirting these regulations in recent years by selling “ghost gun kits”—partially-completed guns that you can make fully operational in the time it takes you to make lunch. All someone has to do is put a couple pieces together or drill a few holes, and the finished product has all the killing capacity of a regular gun, with none of the licensing or traceability.

These are selling points for people who can’t pass a background check—such as young people or domestic violence offenders—and people who plan to use them to commit crime. And between 2017 and 2021, there was a 1,000 percent increase in the number of ghost guns recovered by law enforcement as part of criminal investigations, according to Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who argued the case for the government. The Biden administration addressed this surge in 2022 by issuing a rule underscoring that the laws that apply to regular firearms apply to Easy-Bake Oven-style firearms, too. In VanDerStok, gun advocates and manufacturers are challenging the legality of the rule, alleging that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, or ATF, exceeded the authority granted to it by Congress.

That argument can easily be put to rest by simply reading the Gun Control Act and the regulation, and most of the justices did not appear to buy it. But it’s easy to see why the gun lobby would push its luck: The Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to rewrite the country’s gun policies twice in as many years, including in a very similar case just a few months ago: In Garland v. Cargill, the Court held that the ATF exceeded its statutory authority by issuing a rule saying that bump stocks, which make semiautomatic firearms function like machine guns, are subject to the same regulations as machine guns. VanDerStok follows the same pattern: The ATF issued a rule to close a loophole and make sure a gun by another name couldn’t circumvent federal law. So, the gun lobby had reason to think conservative justices would again come to their aid.

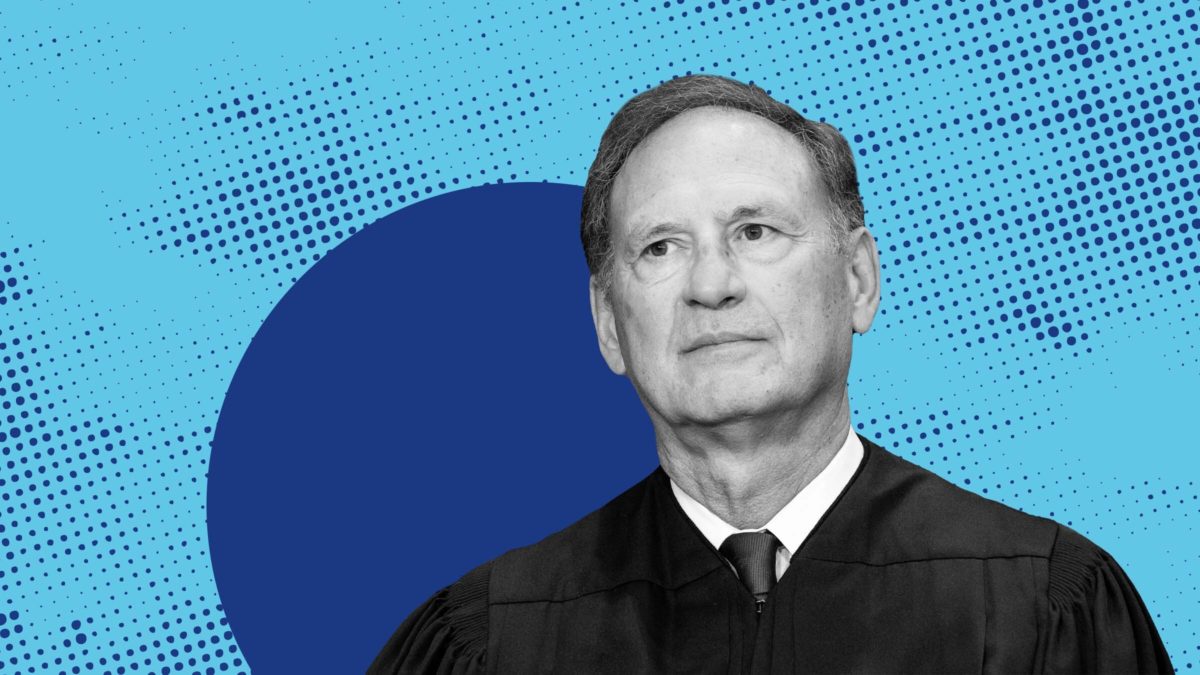

Somewhat surprisingly, only Justice Samuel Alito seemed truly eager to do so. Even though the text of the Gun Control Act applies to weapons that are “designed to or may readily be converted” to be firearms, Alito argued that component parts needed to assemble a weapon should not be treated as a weapon itself—and relied on a series of progressively asinine analogies to make his point.

“Here’s a blank pad, and here’s a pen, all right,” Alito began. “Is this a grocery list?” Prelogar responded by pointing out that a paper and pen could be used to create plenty of things other than grocery lists: Sure, I could use them to jot down a reminder to buy more milk, but I could also make a paper airplane, or draw a picture, or write a letter to Sam Alito telling him he’s not nearly as clever as he thinks he is. This makes them fundamentally different from ghost gun kits, which are explicitly intended to be used to make guns, and not anything else.

When you’re hungry (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Alito tried again. “I put out on a counter some eggs, some chopped-up ham, some chopped-up pepper, and onions,” he said. “Is that a western omelet?” Prelogar again explained why the answer is no. “Those items have well-known other uses to become something other than an omelet,” she said. Instead of making an omelet, someone could get eggs to throw at Alito’s house on Halloween. (I’m joking, National Review.) But again, the only reason to get a ghost gun kit is to make a ghost gun.

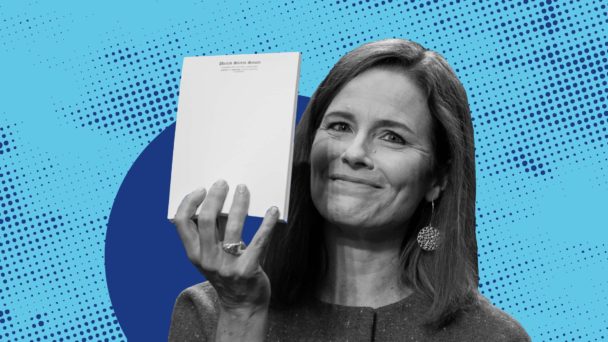

At this point, Justice Amy Coney Barrett got involved. “I just want to follow up on Justice Alito’s question about the omelet,” Barrett said. “Would your answer change if you ordered it from HelloFresh and you got a kit, and it was like turkey chili, but all of the ingredients are in the kit?” This time, Prelogar answered in the affirmative, distinguishing “scattered components that might have some entirely separate and distinct function” from something marketed and sold as a meal kit.

Justice Alito: “Is it the case that components that can easily be converted into something constitute that thing before they are converted…if I show you, I put out on the counter some eggs, some chopped up ham, some chopped up pepper and onions, is that a Western Omelet?” pic.twitter.com/W8VmYywRfF

— CSPAN (@cspan) October 8, 2024

It is bewildering that the success of an attempted end-run around the nation’s gun policies could depend even a little bit on the jurisprudential equivalent of asking whether a Pop-Tart is a ravioli. But that is the power the Court has taken for itself. Last term, in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, it overruled a 40-year-old precedent that had governed how courts assess the legality of agency rules like this one, which opened the door for a Republican-stacked judiciary to second-guess every policy crafted by a Democratic administration.

At oral argument, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said she is “worried” about “the Court taking over what Congress may have intended for the agency to do in this situation.” Jackson recognized that judges’ mere disagreement with an exercise of discretion shouldn’t make an agency action unlawful—“It can’t be assumed that the agency exceeds its authority whenever it interprets a statutory term differently than we would,” she said—and rejected the idea that the Court’s job is to “just decide what we think a firearm is.”

At least this time, the Court seems prepared to decide that a gun is a gun. But this result would be hard to celebrate when it should never have been the Court’s decision to make in the first place.