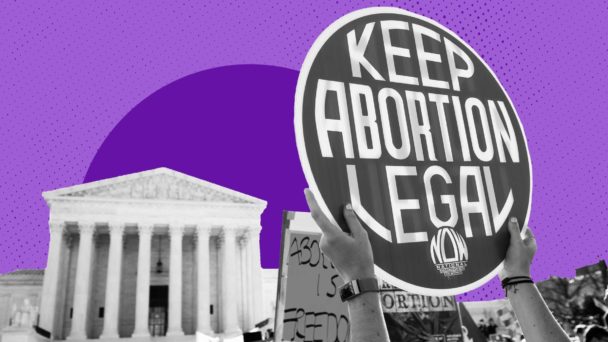

On Monday, the Supreme Court officially began its new term. If you had no idea the Court’s term ever ended, that’s understandable: The Trump administration peppered the Court with emergency petitions throughout the justices’ traditional summer break, and the Republicans on the Court dutifully raced to grant them, allowing Trump to upend lives and laws without so much as briefing, oral argument, or reasoned explanations.

This morning’s oral argument in Villarreal v. Texas, however, suggested that the Court still remembers the proper way to ignore the Constitution—and can even find common ground when it does so. Aggressive questioning from both Democratic and Republican justices exposed what has been a longtime hallmark of the Court’s jurisprudence no matter who has controlled it: a blithe indifference to the rights of criminal defendants.

The petitioner in the case, David Villarreal, was on trial in San Antonio in June 2018 for the murder of Aaron Estrada, his boyfriend. Villarreal was high and paranoid one day, and tried to get Estrada to turn off all phones, computers, and cameras, because he was afraid he was being watched. When Estrada refused, Villarreal turned off all the switches in the breaker box himself and pulled out all the smoke detectors. Their fight turned physical—Villarreal says Estrada choked him and he was afraid he would die—and then he fatally stabbed Estrada.

Villarreal took the stand as the only defense witness, but the judge, Jefferson Moore, had a scheduling conflict that arose during Villarreal’s testimony. So, in the middle of Villarreal’s direct examination, the judge declared a 24-hour recess, and instructed Villarreal and his attorneys that they could not talk about his testimony during those 24 hours.

“Normally your lawyer couldn’t come up and confer with you about your testimony in the middle of the trial and in the middle of having the jury hear your testimony,” said Moore, “and so I’d like to tell you that you can’t confer with your attorney.”

The judge knew he couldn’t impose a blanket ban on communications, though: The Sixth Amendment to the Constitution guarantees that people accused of crimes shall “have the assistance of counsel for his defense” in criminal prosecutions. Five decades ago, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Geders v. United States that trial courts violate the Sixth Amendment if they prohibit defendants from conferring with their attorneys “about anything” during an overnight recess between a defendant’s direct examination and their cross-examination.

In 1989, though, the Court held in Perry v. Leeke that there’s no Sixth Amendment problem if trial courts prohibit defendants from conferring with their lawyers during a 15-minute recess. In other words, there’s a big window between 15 minutes and overnight that the Court has yet to constitutionally account for. So, Moore tried to thread the needle by instructing the defense attorneys to pretend Villarreal was still on the stand, and to conduct themselves accordingly. “I don’t want you discussing what you couldn’t discuss with him if he was on the stand in front of the jury,” he said. Villarreal resumed testifying the following day, was convicted of murder, and sentenced to 60 years in prison.

(Photo by Celal Gunes/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Villarreal now argues that this violated his Sixth Amendment rights. Nine of 13 federal appeals courts to consider the issue would agree with him. Those courts held that trial judges may not prohibit a defendant and their attorney from discussing their testimony during a “substantial” recess—the Fourth Circuit even said that it would “defy reason” to do otherwise. But at oral argument, the justices didn’t seem to understand what the big deal was.

“In the judge’s instructions, he says: ‘I don’t want you discussing what you couldn’t discuss with him if he was on the stand in front of the jury,’” Justice Clarence Thomas asked Villarreal’s lawyer, Stuart Banner. “What’s wrong with that?”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said Thomas was making “a critical point.” If a lawyer can’t prep the witness while they’re on the stand, Jackson asked, “why should he be allowed to do so during an overnight recess?” Jackson also emphasized that the trial court wasn’t making a big imposition: Under this rule, a defendant could still talk to their lawyer, but not about their testimony—in Jackson’s words, “just eliminating that very narrow category of conduct.”

Banner replied that such a distinction between trial strategy and trial testimony is often impossible to make in practice. “To even call it a line is wrong,” said Banner. “It’s not a line. It’s a Rorschach blot, right?” Then Justice Elena Kagan jumped in: “But that’s the line that Perry drew.” When Banner said Kagan was trying to draw the same fuzzy line as the lower court, Kagan cut him off: “I’m not trying to draw it. I’m suggesting that Perry says it right here on page 284.” At this, Thomas laughed.

The point Banner was trying to make, which was apparently lost in the midst of the justices’ chuckles, was that questions about trial strategy and questions about trial testimony are often the same questions. This may even be especially true in Villarreal’s case, where he’s the only witness and is claiming that he acted in self-defense. Yet the Court treated his ability to speak to his attorney about testimony as if it were something trivial, and not possibly the difference between spending 60 years in a cage or not.

The Supreme Court has a long history of disregarding if not openly disdaining the rights of people accused of crimes whose cases appear on the merits docket (and whose names aren’t “Donald Trump.”) Over the summer, the Court had other things to attend to—namely, granting the administration’s every wish. Now it’s getting back to basics.