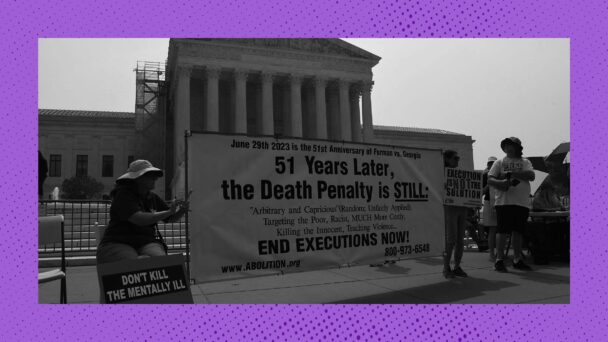

The Supreme Court heard oral argument on Tuesday in Wolford v. Lopez, a case about whether states can ban people from carrying concealed firearms on private property without getting the owner’s consent. Under the Hawaii law at issue, any armed person who wants to enter a shopping center, restaurant, or other privately owned property that is open to the public needs “express authorization” first—for example, a sign at a store’s entrance or a verbal “okay” from an employee. Gun laws like Hawaii’s are often called “vampire rules” because, like the rules that applied to vampires in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, they keep out a deadly threat unless the deadly threat receives an explicit invitation to enter.

Hawaii enacted its law in 2023 in response to New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, a 2022 Supreme Court case that created a new test for determining the constitutionality of gun control laws. Under Bruen, laws that regulate “the right of the people to keep and bear arms” violate the Second Amendment unless there is a “well-established and representative historical analogue.” This rigid standard calls on courts to invalidate all gun laws unless, in a judge’s estimation, people in the Founding era imposed similar restrictions for similar reasons.

Bruen immediately caused chaos in the lower courts, as it called the legality of previously uncontroversial gun laws into question. And in July 2024, after a federal appeals court ruled that laws disarming domestic violence offenders are unconstitutional because the country did not historically disarm domestic abusers, the Court began to backpedal. Writing for the eight-justice majority in United States v. Rahimi, Chief Justice John Roberts explained that lower courts had “misunderstood” Bruen, and that modern gun safety laws need only a historical “analogue,” not a historical “twin.” (For what it’s worth, the author of Bruen, Justice Clarence Thomas, dissented in Rahimi to say that the lower court had understood his opinion just fine.)

Wolford v. Lopez is the Court’s second confrontation with the absurdities produced by Bruen’s embrace of originalism, the idea that the Constitution has one true, historically discoverable meaning. At oral argument on Tuesday, the Republican justices were deeply disturbed that Hawaii defended its statute in part by pointing to an 1865 Louisiana law that prohibited people from entering private property with guns “without the consent of the owner or proprietor”—a statute that lawmakers originally adopted in order to disarm Black people. Nodding to the genesis of the “vampire rule” nickname, Justice Neil Gorsuch marveled at the fact that “a lot of people” who would normally react to historical anti-Black laws like “garlic in front of a vampire” are now citing them to promote gun restrictions. “I’m really interested in why,” he said.

The Bruen opinion, which Gorsuch joined, contains the answer to his question. State lawmakers digging up historical gun regulations to justify modern gun regulations are simply doing what the Court told them to do. It is not their fault that many historical gun regulations are racist.

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Wolford began in June 2023, when members of the Hawaii Firearms Coalition filed a federal lawsuit arguing that the vampire rule lacked a Bruen-compliant historical analogue. In August 2023, the district court agreed, issuing a preliminary order that blocked Hawaii from enforcing the statute while the case challenging its legality was ongoing. But in September 2024, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed; writing for the three-judge panel, Judge Susan Graber placed special emphasis on the 1865 Louisiana law, as well as a 1771 New Jersey law prohibiting people from carrying “any gun on any lands not his own” unless “he hath license or permission in writing from the owner.”

At oral argument on Tuesday, Gorsuch lobbed a softball to the challengers’ attorney, Alan Beck, asking if it was appropriate for the Graber and the Ninth Circuit to rely on a law “aimed at Freedmen” in the aftermath of the Civil War. “Do you think the Black Codes, as they’re called, should inform this Court’s decisionmaking when trying to discern what is this nation’s traditions?” he asked.

Beck had the good sense to say no. But Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson soon chimed in, basically asking why Hawaii’s reference to the Louisiana law should reflect poorly on Hawaii’s prohibition rather than the Court’s precedent. “To the extent that we have a test that relates to historical regulation, but all of the history of regulation is not taken into account, I think there might be something wrong with the test,” she said. Jackson went on to argue that there exists an important distinction between acknowledging that the country has “moved away from that history” and pretending that “that history didn’t exist.”

In an exchange with Deputy Solicitor General Sarah Harris, who represented the Trump administration in its support for the challengers, Gorsuch again invoked the Black Codes, asking Harris whether the Court “really should consider them as significant here.” Harris, who, just to reiterate, works for President Donald Trump’s Justice Department, also said no, calling it “somewhat astonishing” that the Black Codes “are being offered as evidence of what our tradition of constitutionally permissible firearm regulation looks like.”

Jackson again pushed back. “The Black Codes were being offered here under the Bruen test to determine the constitutionality of this regulation, and it’s because we have a test that asks us to look at the history and tradition,” she said. “The fact that the Black Codes were at some later point determined themselves to be unconstitutional doesn’t seem to me to be relevant to the assessment that Bruen is asking us to make.”

Harris started to respond by saying that Black Codes should have been unconstitutional “from the moment of their inception,” but Jackson cut her off. “Let me stop you there. They were not deemed unconstitutional at the time that they were enacted,” she said. “They were part of the history and tradition of the country.”

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Gorsuch returned once more to the Black Codes at oral argument, asking the state’s lawyer, Neal Katyal, to defend this “astonishing” argument. Katyal agreed that the Black Codes are “undoubtedly a shameful part of our history,” but argued that this particular Louisiana statute was still relevant, for several reasons. First, when the Reconstruction Congress readmitted Louisiana and other states to the Union, it invalidated many of the Black Codes but left the 1865 law alone, implicitly ratifying it as legitimate. Second, when General Daniel Sickles issued an order overriding the Black Codes, he clarified that the right to bear arms did not “authorize any person to enter with arms on the premises of another against his consent.”

At this point, Justice Samuel Alito interrupted, arguing that post-Reconstruction laws in the South disarmed Black people “precisely to prevent them” from exercising their Second Amendment right to defend themselves—against the Ku Klux Klan and racist law enforcement officers, among many others. “Is it not the height of irony to cite a law that was enacted for exactly the purpose of preventing someone from exercising the Second Amendment right—to cite this as an example of what the Second Amendment protects?” Alito asked.

Katyal responded that many Black Codes did operate in that way, but this particular Louisiana law did not. “If anything, it protected Black churches and Black-owned businesses and the like by insisting on this consent rule,” said Katyal. “That is why the radical Reconstruction Congress admitted Louisiana back in [to the Union].”

Bruen was supposed to be a capstone achievement for originalism, which conservative lawyers have pushed for decades as the only correct methodology for interpreting the Constitution. But the questions at the Wolford oral argument demonstrate just how much flexibility the theory gives to judges looking for ways to enact their policy preferences. To block modern gun laws, justices only need to invoke concerns loosely tied to the 19th century. To pass gun laws, legislators must rely on history, and be sure to set aside any history the Republican justices wish to forget.