Arguing with the police is, theoretically, your constitutional right. Police officers are, also theoretically, prohibited from arresting you because you said something they don’t like. However, if that police officer can later come up with an entirely different reason for the arrest—even when they admit they’re just making up that reason—you’re probably out of luck.

That’s what happened several years ago to Mason Murphy, who was walking on the wrong side of the shoulder of a rural road in Missouri when a police officer, Michael Schmitt, stopped him. Murphy refused Schmitt’s request to identify himself, and, after several minutes of argument, Schmitt arrested him for, in Schmitt’s words, “failure to identify.” Several states have “stop and ID” laws that require people to identify themselves to law enforcement when asked. Outside of Kansas City, Missouri has no such law, but didn’t deter Schmitt: Body camera footage shows that upon their arrival to the station, Schmitt got on the phone and told someone that he “saw the dip shit walking down the highway, and he would not identify himself.” Schmitt then asked a question that will not be appearing in Back The Blue promotional materials anytime soon: “What can I charge him with?”

Perhaps because there was genuinely nothing to charge him with, Murphy was let go after about two hours in a jail cell. And in October 2021, Murphy sued in federal court, arguing that he was arrested for exercising his First Amendment right to argue with police. His case is pretty simple and theoretically strong: The officer first told Murphy he was being arrested for a thing that is not a crime. Then, the officer used his phone-a-friend lifeline to see if there was something else he could arrest him for. At various points during the incident, Schmitt told people at the station that Murphy had been stumbling and walking on the wrong side of the road; that Murphy “would not identify himself” and “ran his mouth off;” and that Murphy was drunk and had to “sit here for being an asshole.”

To win a First Amendment retaliation claim, people like Murphy have to prove three things, according to the court here. First, they must have been engaged in a protected activity. Next, the officer has to take an “adverse action” against the plaintiff that would “chill a person of ordinary firmness” from continuing the activity. Finally, the plaintiff has to show that the action was motivated, at least in part, by the plaintiff’s exercise of their First Amendment rights.

Again, Murphy’s case should be a slam dunk: He argued with a cop, the cop got annoyed, and Murphy ended up in jail as a result. But thanks to a 2019 Supreme Court case, Nieves v. Bartlett, it isn’t. Instead, a three-judge panel of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, relying on Nieves, ruled in Murphy v. Schmitt that Murphy could not recover anything, because Nieves made it much harder to win First Amendment retaliation claims against cops.

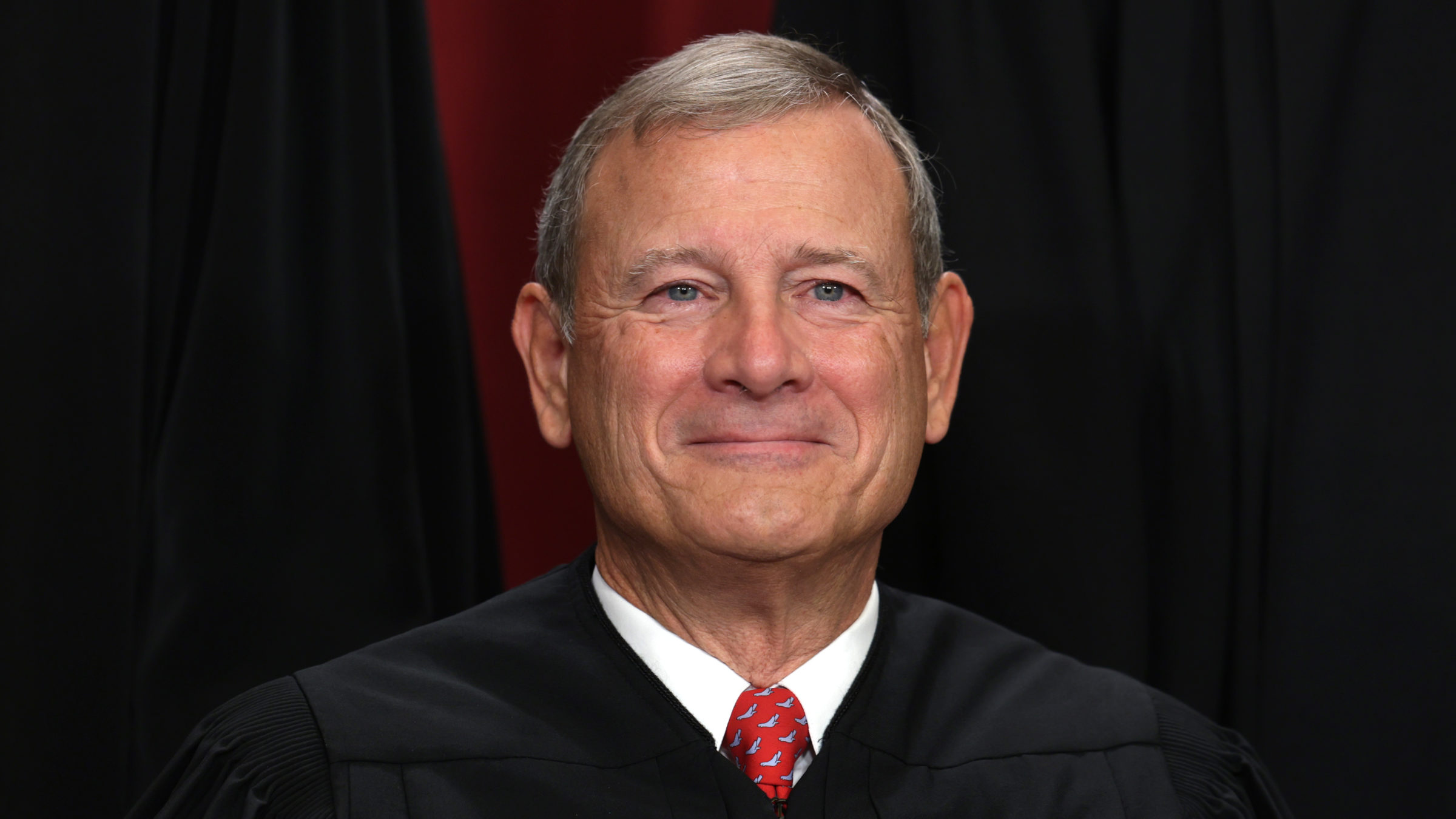

Nieves wasn’t even one of the hot cases of the 2018-2019 Supreme Court term. But in Nieves, the Court created a substantial new barrier to retaliatory arrest claims by making a significant addition to the three-prong test: Now, a plaintiff also has to show that the officer had no probable cause to arrest them for any crime. Under this rule, the statements and motivations of the arresting officer are “irrelevant.” Writing for the majority Chief Justice John Roberts, crafted a narrow exception: If a person complaining about or arguing with police gets arrested for some minor violation like jaywalking in a place where jaywalking is “endemic,” they might clear the no-probable-cause hurdle by presenting “objective evidence” that “otherwise similarly-situated individuals” were not arrested for doing the same thing.

This sounds nice, but in dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor explained how unworkable this approach is in real life. The hypothetical jaywalker, she argues, couldn’t just point to retaliatory statements made by the arresting officer, but would instead have to provide complete information about everyone else who has ever been arrested—or not arrested—for the same thing.

Murphy argued that Schmitt’s behavior here fit into the Nieves exception, alleging that “a reasonable opportunity for further investigation” would show no one had been detained or arrested for walking on the wrong side of the road in this area; that walking on the wrong side of the road happens all the time on highways with wide shoulders; and that officers typically didn’t arrest people for it. But the Murphy majority seized on just one word in Roberts’ hypothetical: “endemic.” The majority said that even if everything Murphy said were true, it wouldn’t show that violations were so common as to be “endemic.” On this basis, it upheld a lower court’s grant of qualified immunity to Schmitt.

When you hear the ‘COPS’ theme (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

The decision highlights exactly what Sotomayor warned would occur in her Nieves dissent: For normal people, finding a large number of people who may or may not have been arrested for the same behavior is functionally impossible. Most of the time, an arrested person doesn’t have a readily determinable pool of people to point at to argue that others weren’t arrested. Instead, they have to somehow, before even filing a lawsuit, procure objective statistical proof that the law under which they are arrested is seldom enforced despite “endemic” violations of it. Because Mason Murphy had not already obtained a vast trove of data about walking on the wrong side and arrests in Missouri, the court decided he has no recourse.

The Eighth Circuit isn’t alone in treating Nieves like a get-out-of-court-free card for cops. The Sixth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits all deployed Nieves to deny retaliatory arrest claims. So has the Fifth Circuit, which, in Gonzalez v. Trevino upheld the arrest of a Castle Hills, Texas city councilmember who organized a petition to remove a city manager, and was charged under a state law that bars concealing, removing, or otherwise impairing a government record’s verity, legibility, or availability. The court agreed that Gonzalez had shown that nearly everyone else prosecuted under that law was prosecuted for, for example, faking driver’s licenses. Nevertheless, the Fifth Circuit decided that wasn’t enough, because Nieves requires “comparative evidence” that other similarly-situated individuals who engaged in the same conduct were not arrested. In other words, even though Gonzalez was able to show no one was prosecuted for her behavior, she failed the Fifth Circuit’s new test: needing to show there were people who engaged in her exact behavior but were not charged.

Gonzalez has petitioned the Supreme Court to hear her appeal. Even if the justices grant it and clarify Nieves, however, people who endure unjustified arrests would still have an uphill climb in their efforts to recover. As long as the legal system allows police to gin up harebrained excuses for arresting someone whose protected speech pissed them off, they have no reason to fear the consequences.