Conservatives are very upset about “junk science” in the courtroom—now that it is harming corporations. According to outlets like the Wall Street Journal and Real Clear Science, there is a “victim-industrial complex” encouraging people harmed by corporations to see themselves as “victims entitled to someone else’s money.” These commentators also say that “junk science is in vogue” in civil lawsuits against big business, and such class action lawsuits “destroy innovation.”

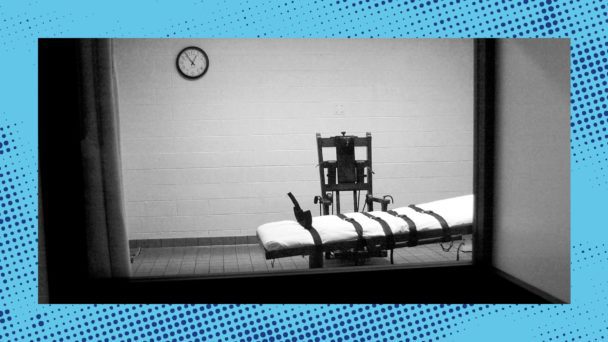

Typically, the victims of actual junk science are ordinary people, particularly criminal defendants. Prosecutors consistently use a glut of junk science to lock people up on shaky grounds or even put people on death row for imaginary crimes. Yet conservative heroes are mostly concerned for poor corporations having to compensate the people they harm with their products. And despite some recent changes to evidentiary rules that make it even harder for plaintiffs to win lawsuits, business allies are still crying that the system does not favor corporate defendants enough.

Judges’ decisions about whether to admit testimony from expert witnesses at trial are based on Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence, which has long required judges to determine if expert testimony is the “product of reliable principles and methods.” But the corporate defense bar lobbied for an amendment for a stricter standard. In April 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court approved an amendment requiring judges to admit expert testimony only when it is more likely than not that the expert has reasonably applied those principles and methods to the facts of the case.

Rule 702, along with the clarifying amendment, is based on a test the Supreme Court first articulated in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc.. The rule put the judge in the role of “gatekeeper” to ensure that only scientifically sound expert testimony is admitted. According to conservative commentators and corporate lawyers, judges were not following the rule, so it needed to be clarified. This conclusion was mostly based on the fact that companies were still losing product liability cases. When businesses are so accustomed to the U.S. legal system papering over corporate malfeasance, it probably feels unfair for harmed plaintiffs to win a case every once in a while.

Interestingly, much of the legal firepower advocating for changing the evidence rule did not come from the criminal legal space, where prosecutors routinely use discredited forensics techniques to put people in prison for life, but from the corporate defense bar. Discrediting science harmful to the bottom line is a tried and true tactic for corporations seeking to avoid accountability for their actions. The paradigmatic example is the tobacco industry, which spent decades funding its own studies on the effects of tobacco to muddy the otherwise clear scientific consensus about its harms. This campaign delayed the regulation of cigarettes and contributed directly to avoidable deaths of smokers, keeping them and their families from receiving compensation or treatment until it was too late for many of them.

The tobacco playbook taught other big businesses the value of funding their own corporate-friendly science and using that to sow doubt on plaintiffs’ experts. But since competing evidence is no guarantee of a win in court, corporations and their conservative allies started to run a parallel effort to work the refs, asking judges to stop admitting evidence that products are harmful. Industry groups claimed judges were not following Rule 702 and Daubert when they admitted anything less than bulletproof causation evidence of harm by corporate products. Corporate defense attorneys enlisted conservative law professors to publish articles on the supposed need for amendments to Rule 702. Unsurprisingly, these recommendations all had one thing in common: They would have made it much easier for corporations to exclude scientific evidence that their products were harmful.

These proposed amendments would have added an “objectively reasonable” standard, similar to those that have introduced considerable subjectivity and a regressive bias in other legal analyses. They would have also called for experts to not reach conclusions with “resort to unsupported speculation,” without defining what “unsupported” means. This could have seriously disadvantaged plaintiffs because scientists generally hedge their answers, since nothing can be known for certain in basic research. Most of these proposed changes were not adopted, but they do give away the game in the corporate defense bar’s approach to weaponizing the circumspect nature of science against plaintiffs.

The main problem with insisting on certainty in scientific evidence is that there is no such thing as certainty in science. Basic science seeks to give the best answers to problems by testing hypotheses and ruling out possibilities, but there is always room for doubt about any given theory. Those best answers come as a result of consensus across studies. Corporate defendants know this all too well, as demonstrated by their campaigns to obscure that consensus with their own studies.

Beyond asking the impossible of scientific witnesses, the corporate defense bar has been propagating a myth that junk science is being privately funded for use against corporations. However, anyone who has thought for more than a second about power imbalances in civil litigation has probably correctly identified corporations as the overpowered party in almost every case they are involved in. Despite this plain fact, industry groups would have us believe that the plaintiffs’ bar is all-powerful and is taking advantage of corporations to enrich themselves. This is a fantasy from which the real people harmed by corporations are mostly absent. This tactic is all the more laughable considering that corporate defendants commission significantly more studies than plaintiffs’ firms. But this does not stop conservatives from telling spooky stories about big, scary plaintiffs’ firms taking advantage of supposedly flimsy studies so they can line their pockets at the expense of hard working CEOs.

For conservative business interests, asbestos class action lawsuits are one such cautionary tale. Cases against companies manufacturing or using asbestos successfully generated significant compensation for people who were sickened or killed. Yet industry groups and conservative think tanks claim bad science bankrupted upstanding companies that were just trying to make America a little more fireproof.

In reality, researchers—and corporations—knew that asbestos exposure caused serious health problems as early as the 1930s. Rather than address the problem, corporations and the government worked to cover up the evidence, with the government excluding asbestos from mandatory testing regimes under usual government regulations. Corporations also spent huge sums on research to discredit the plain findings of multiple independent studies. One report found that Ford spent over forty million dollars on initiatives designed to discredit the links between asbestos and cancer.

Now that corporations have their rule change, you might expect them to be satisfied. Since the Supreme Court approved the amendment, industry groups and corporate firms have celebrated dozens of cases of judges excluding expert testimony in product liability suits. However, the same people are still making the same complaints, with industry-associated commentators like the Drug & Device Law Blog calling cases where judges admitted harmful testimony “atrocities.”

High-profile exonerations in criminal cases have generated legitimate (and overdue) public concern about the use of discredited forensic techniques in the legal system. But corporations and their lawyers have leveraged this attention—and their deep pockets—to cast themselves as the real victims of junk science. Unfortunately for the rest of the country, they might just have the money and political power to pull it off.