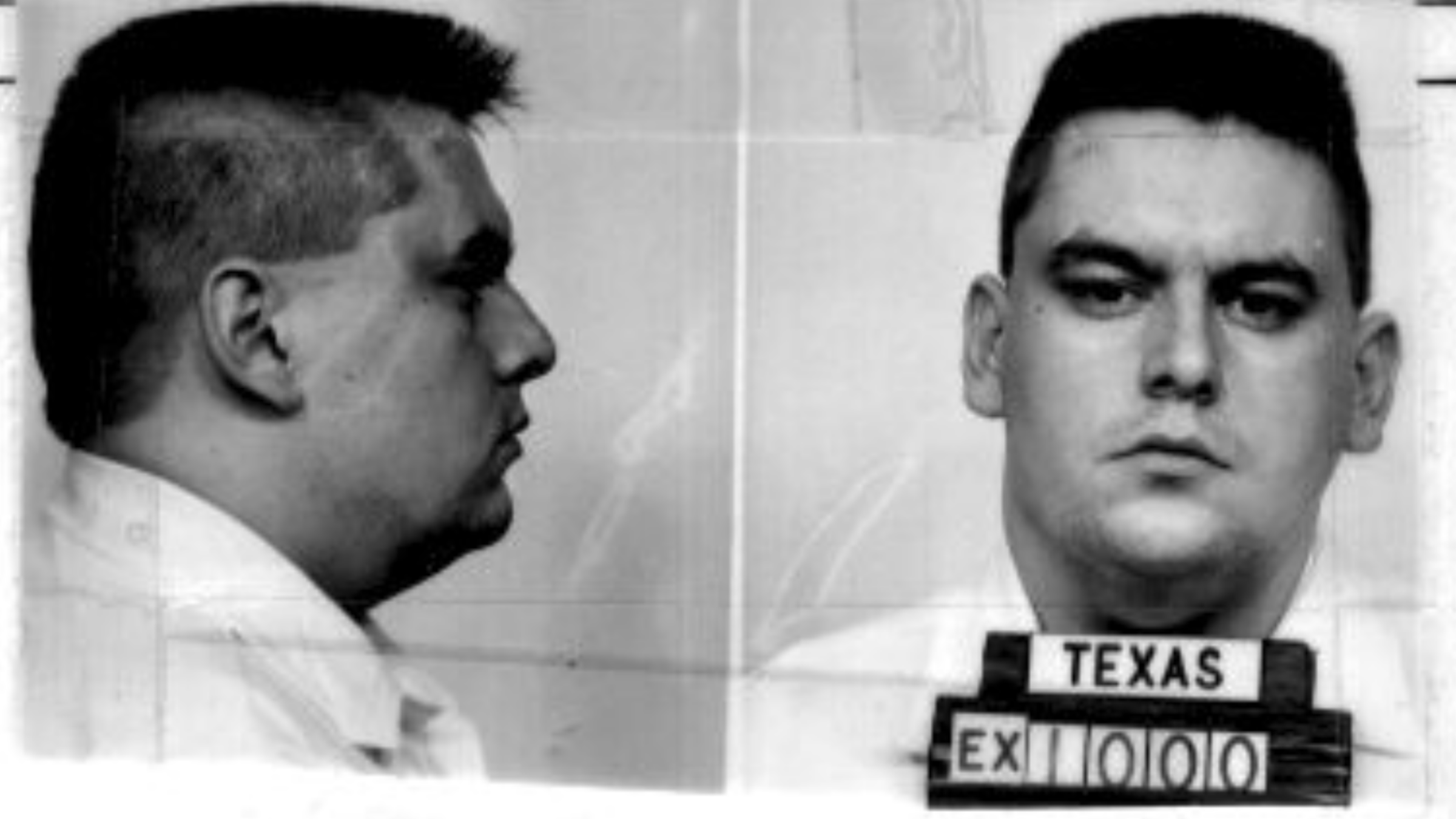

By April 1990, 19-year-old Brent Brewer was in the midst of a full-blown crisis. A few weeks earlier, he’d been released from a hospital in Texas, where he’d been involuntarily committed for several months after his grandmother, with whom he was living, found a suicide note he’d written. In the midst of a relapse and with no place to stay, Brent and his girlfriend, whom he’d met at the hospital, asked a flooring store owner named Robert Doyle Laminack for a ride to an Amarillo-area Salvation Army. In the car, Brent and his girlfriend tried to rob Laminack at knifepoint. In the ensuing struggle, Brewer stabbed Laminack in the neck, killing him.

At Brewer’s trial the following year, the state called Dr. Richard Coons as an expert witness. Coons, who had never met Brent in person, nonetheless told jurors that Brent would “probably” join a gang in prison, portraying him as a terminally dangerous menace to society. The jury that heard Coons’s testimony convicted Brent and sentenced him to death.

Almost two decades later, however, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the death sentence in a 5-4 opinion, faulting the court’s failure to allow jurors to adequately consider evidence of Brent’s troubled childhood and his ongoing struggles with depression, anxiety, and substance use. His stepfather, who moved into the house when Brent was four years old, would beat him with belts and extension cords. When Brent was a teenager, his mother divorced his stepfather and married his biological father, who was no less abusive: At age 15, Brent had to use a broom handle to defend his mother from his father’s latest assault.

Juries in capital cases, wrote Justice John Paul Stevens in Brewer v. Quarterman, must be able to weigh this evidence “in a reasoned, moral manner” before determining “whether a defendant is truly deserving of death.”

The state of Texas, as stubborn as it is bloodthirsty, sought another death sentence. Again, prosecutors called Coons to the witness stand, who parroted much of his earlier testimony, again without ever meeting with Brent in person. Coons testified that Brent would “more likely than not” commit acts of violence in the future and had no “conscience.”

On cross-examination, Brent’s lawyers pointed out that his behavior while on death row—four citations in 10 years, one for having too many towels in his cell—sort of undermined Coons’s “expert opinion” that Brent would likely kill again if the state did not kill him first. Coons asserted that “a huge amount” of prison violence goes unreported, and that Brent’s disciplinary record was thus not a reliable gauge of his dangerousness. After Brent’s lawyers decided not to object to the admissions of Coons’s testimony, the jury sentenced Brent Brewer to death for a second time in 2009.

An undated photo of Brent Brewer (Image via Texas Department of Criminal Justice)

Among the myriad problems with this case is that Coons was, to use a technical term, full of shit. In a separate case in 2010, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals noted that Coons, who had testified as an expert in dozens of capital trials like Brent’s, was unable to point to “books, articles, journals, or even other forensic psychiatrists who practice in this area” to substantiate his self-developed methodology, and simply explained that he “does it his way.” Although the court acknowledged that Coons’s methodology might have “great intuitive appeal” to jurors, it was not scientifically reliable. Coons also claimed to have never followed up on his predictions of future dangerousness to check them for accuracy—predictions that, as for Brent, could be the difference between life in prison or a death by lethal injection.

To date, however, no court has found that any of this, legally speaking, actually matters. In 2012, Brent challenged his sentence in Texas state court, arguing that his lawyers’ failure to challenge Coons’s testimony amounted to ineffective assistance of counsel. The judge agreed that Brent’s trial counsel made a mistake, but decided that Brent wasn’t prejudiced by it—that is, the mistake hadn’t made a difference in the jury’s decision to sentence him to death. (Even if Coons hadn’t testified, the judge wrote, there was “ample evidence” of Brent’s supposed predilection for violence sufficient to support the jury’s decision.) The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed, but over the dissent of one judge who would have thrown out his sentence.

Brent fared no better in federal court, where in 2022, Judge Matt Kascmaryk—a Trump appointee better known for unilaterally appointing himself the nation’s medication abortion czar—decided that since Coons wasn’t exposed as a hack until after Brent’s sentencing, Brent’s lawyers weren’t responsible for lacking the “clairvoyance” to object to Coons’s testimony a year earlier. Kacsmaryk thus concluded that the Texas state courts that reviewed Bren’ts case “did not act unreasonably in holding that trial counsel were not ineffective for failing to make…a ‘futile’ objection”—a curious assertion, given that no state court had concluded an objection would be futile. Earlier this year, a three-judge panel of the ultraconservative Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed Kacsmaryk’s opinion.

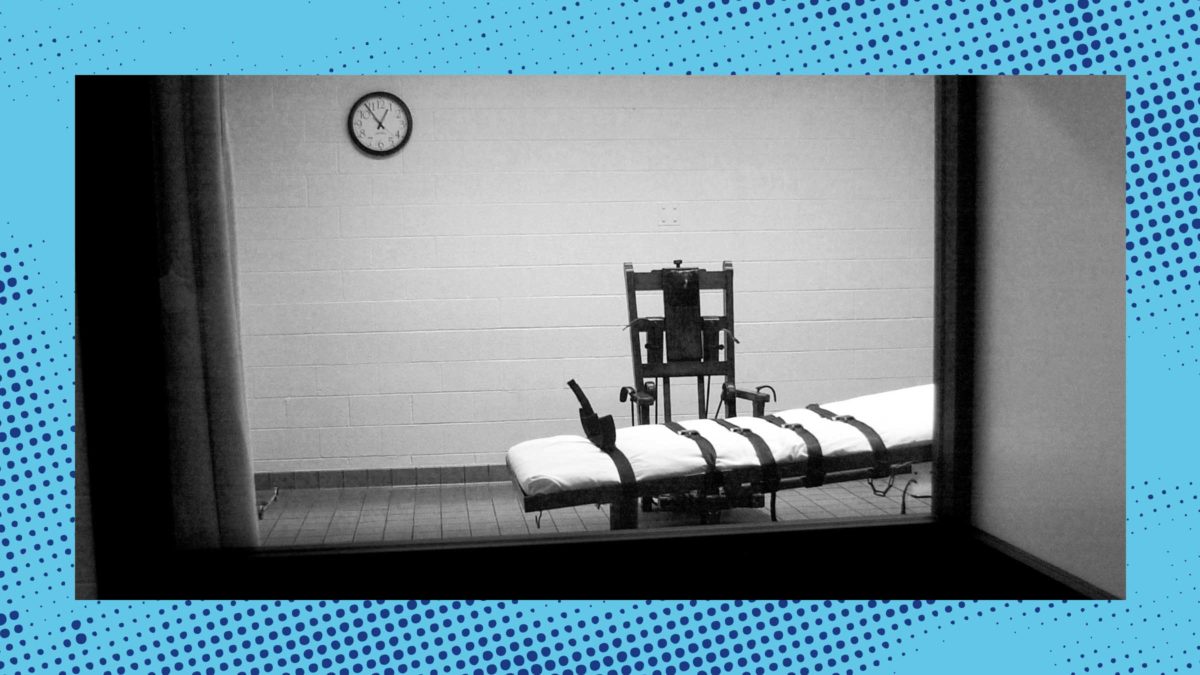

Executions usually take place long after this leg of the appeals process has concluded. But only three weeks after the Fifth Circuit’s decision, while Brent’s lawyers were preparing his appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, Randall County prosecutor Robert Love asked a Texas state court to set Brent’s execution date, which came down several hours later. Now, the Supreme Court will consider Brent’s petition for the first time at the justices’ regular conference on Friday, October 27. As of this writing, his execution is scheduled for November 9—just 13 days later.

The technical question in Brent’s case, Brewer v. Lumpkin, is under what circumstances federal courts must grant “certificates of appealability,” which allow people in Brent’s circumstances to challenge denials of post-conviction relief. His lawyers argue that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals’s divided opinion, along with the contradictory rulings from the state and federal courts reviewing Brent’s case, establish that the issues here are “debatable among jurists of reason”—and, thus, that he should have the chance to make his case.

“A state court judge would have granted relief to Mr. Brewer and vacated his sentence of death. All state courts agreed that counsel performed deficiently in failing to object to [Coons’s] unreliable testimony,” Brent’s lawyers write. “The Fifth Circuit reached its own conclusion on the merits and held the opposite.”

But underlying this fight about dueling legal standards is something less technical but far more dystopian: the very concept of “future dangerousness,” which juries have used to sentence hundreds of people to death despite the fact that it is, according to experts, about as junk science as junk science gets. As early as 1983, the American Psychiatric Association told the Supreme Court that “the unreliability of psychiatric predictions of long-term future dangerousness is by now an established fact within the profession,” and that at least two of three expert predictions of future dangerousness turned out to be flat-out wrong. A study of 155 people on Texas’s death row found eight who’d committed disciplinary infractions in prison that required the provision of treatment beyond first aid; 31 of them had no infractions at all. A 2005 review of available research concluded that clinical assertions about propensity for violence are “highly inaccurate and ethically questionable at best.”

Photo courtesy Brent Brewer

The problem is particularly acute in Texas, which has killed 584 people since the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976—about a third of all executions during that period. Under Texas state law, juries must determine an individual’s future dangerousness in order to impose a death sentence. (As the judge explained in Brent’s case, the jury would have to find a “probability” that, if sentenced to life imprisonment without any hope of release, Brent “would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society.”) The question’s primacy in the legal process gave rise to a small but lucrative cottage industry of so-called experts like Coons, who are paid handsomely to stand before a jury box and somberly explain why This Man Will Kill Again. When he testified at Brent’s resentencing, Coons was billing the state a cool $480 per hour for his services.

Even when dubious expert testimony isn’t involved, research shows that juries are just as bad at making these calls, which a 2017 Atlantic article called “less of a science and more of a guess or moral judgment.” One study of 115 men convicted of capital murder in Oregon concluded that jurors’ predictions about future violence were “completely unrelated to the actual commission of such acts.” In 2013, the American Bar Association recommended that Texas abandon its future dangerous analysis altogether, writing that juries can interpret the concept “so broadly that a death sentence would be deemed warranted in virtually every capital murder case.”

Somehow, Coons’s predictions about Brent’s propensity for deadly violence are even more wrong in 2023 than they were in 1991 or 2009. Since his resentencing, Brent, now 53, has received three additional write-ups for minor violations, including one for lending headphones to a neighbor and another for reaching out to retrieve his box of Frosted Flakes, which guards conducting a shakedown of the pod had left just outside his still-ajar cell door. That’s a total of seven write-ups in 34 years on death row, from a guy who was supposed to be so irredeemably dangerous that putting him to death was the only real option left.

In a country that aspired to do something that looks like justice, the state would not be in the business of killing people, much less killing people on the basis of vibes-based pseudoscience. This is America, however, where capital punishment endures because lofty promises about fair treatment and equal justice under law almost always yield to the basest instincts to avenge and punish. Brent’s case is an opportunity for the Supreme Court to do something about one of the most barbaric features of one of the legal system’s most barbaric institutions. The question is whether the justices feel like exercising their power before Texas’s race to kill Brent before Thanksgiving renders this opportunity moot.