On September 6, 2023, the Senate confirmed Gwynne Wilcox for a second five-year term on the National Labor Relations Board, the independent federal agency charged with protecting and enforcing workers’ rights. Under federal law, NLRB members can only be removed by the president “upon notice and hearing, for neglect of duty or malfeasance in office, but for no other cause.” And Wilcox’s term was scheduled to end on August 27, 2028. Yet late Monday night, Wilcox received a letter from President Donald Trump indicating that she had been fired, along with Jennifer Abruzzo, the agency’s Biden-appointed general counsel who’d used the position to advocate for labor rights.

Wilcox’s removal leaves the Board without the three-member quorum necessary to make decisions, and now hundreds of labor rights cases—many of which involve Tesla, Amazon, Apple, and other companies whose CEOs attended Trump’s inauguration—can’t move forward. Wilcox, the first Black woman to serve on the NLRB in the agency’s 90-year history, expressed regret that the agency will lose her “unique perspective” upon her “unprecedented and illegal removal.” In a statement, Wilcox said, “I will be pursuing all legal avenues to challenge my removal, which violates long-standing Supreme Court precedent.”

The precedent Wilcox was referring to is Humphrey’s Executor v. United States. That case reached the Supreme Court in 1935 after President Franklin D. Roosevelt fired William Humphrey from his position at the Federal Trade Commission, even though the FTC Act said commissioners can only be removed for “inefficiency, neglect of duly, or malfeasance in office.” In that case, the Court unanimously upheld the law’s for-cause removal protections, and concluded that it was “plain under the Constitution that illimitable power of removal is not possessed by the President.”

Humphrey’s Executor has not been overturned, which, if the Supreme Court cared at all about things like “precedent,” would resolve the matter. But Trump’s illegal firing of Wilcox isn’t just based on his abundance of audacity. The conservative legal movement has spent decades chipping away at Humphrey’s Executor and instead promoting the “unitary executive theory,” which insists that presidents have sole authority over the executive branch—and thus, the unfettered power to fire any executive branch employee for any or no reason. The Court’s decades-long embrace of the unitary executive theory laid the groundwork for Trump’s unlawful firing of Wilcox earlier this week.

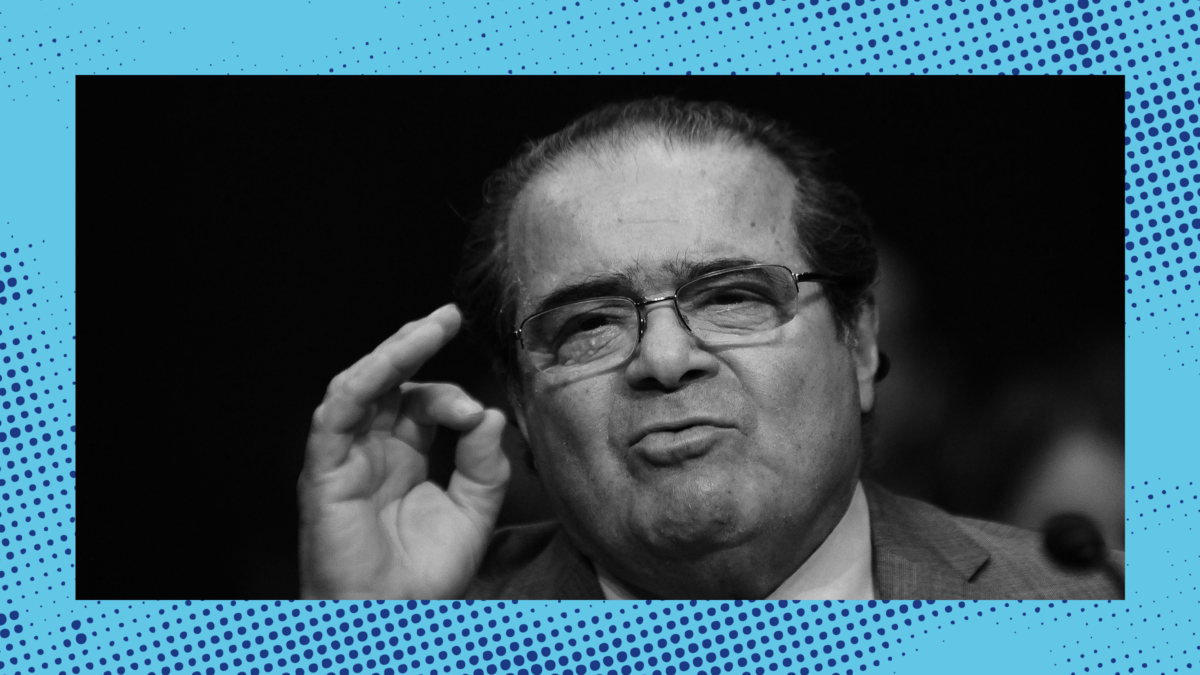

The unitary executive theory began to find its voice on the Court in Morrison v. Olson, a 1988 case that upheld federal ethics law limiting the attorney general’s power to remove independent counsels who are investigating corruption allegations. Justice Antonin Scalia dissented, arguing that Article II of the Constitution, which vests the president with executive power, “does not mean some of the executive power, but all of the executive power.”

No other justices joined Scalia’s opinion in Morrison, but as the Court grew more conservative—and as conservative activists and academics churned out scholarship in support of executive power—adherence to the unitary executive theory became table stakes for any Republican lawyer who aspired to a federal judgeship. By 2020, Scalia’s view commanded a majority on the Court: In Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Chief Justice John Roberts echoed Scalia’s language in Morrison, citing Article II to support the proposition that the president has the “power to remove—and thus supervise—those who wield executive power on his behalf.” Seila Law held that it is illegal for the heads of independent agencies led by a single director to enjoy for-cause removal protections, and reframed Humphrey’s Executor and Morrison as two small exceptions to the president’s otherwise unrestricted removal power.

The following year, in Collins v. Yellen, the Court went even further, ruling that the structure of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, too, was unconstitutional. Like the CFPB, the FHFA is led by a single director who at the time enjoyed for-cause removal protections. But by a 7-2 vote, the justices concluded that statutory restrictions on the president’s power to remove the director were unconstitutional. Justice Elena Kagan wrote a concurring opinion, agreeing that Collins was governed by the result in Seila Law, but maintaining that Seila Law was wrongly decided, and that both cases reflected a questionable political theory not supported by the Constitution.

The Court’s promotion of the unitary executive theory doesn’t just limit Congress’s ability to design and structure new agencies. It also concentrates power in a single individual—and to make matters worse, that individual is currently Donald Trump. The unitary executive theory dresses up a dictatorship in constitutional language, and it is no surprise that Trump has embraced it.