Last June, a New Jersey grand jury returned a blockbuster 111-page indictment of George Norcross III, a state Democratic Party boss allegedly at the center of a vast corruption scheme. He and his brother Philip Norcross were accused of enriching themselves with state-funded tax credits intended to revitalize Camden, the state’s poorest city, and of extorting businesses out of their property rights on the Camden waterfront.

This all came to an end last week, when a state court judge granted Norcross’s motion to dismiss the indictment. The “factual allegations do not constitute extortion or criminal coercion as a matter of law,” said Judge Peter Warshaw, Jr., who also concluded that the charges were time-barred by the state’s statute of limitations.

New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin has pledged to appeal, and quickly put out a statement reflecting on how important public corruption cases are—and how challenging they are to win. “After years in which the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently cut back on federal public corruption law, and at a time in which the federal government is refusing to tackle corruption, it has never been more important for state officials to take corruption head on,” said Platkin. “But I have never promised these cases would be easy.”

One of the reasons these cases are so hard is the U.S. Supreme Court, which has been actively making it easier for public officials to engage in corruption. In the past decade alone, the Supreme Court has reversed several headline-grabbing public corruption convictions. By shrinking the scope of government officials’ behavior that is unlawful, the Court is necessarily expanding the scope of behavior for which purported public servants can’t be held accountable.

First, there was the case of former Virginia governor Bob McDonnell, who used his office to help a local dietary supplement company get a product classified as a pharmaceutical by the Food and Drug Administration. Pharmaceutical classification often requires expensive testing—unless a friendly governor like McDonnell can get the state’s public universities to conduct the testing for you. In return for these services, the company’s CEO handsomely rewarded McDonnell’s family with upwards of $175,000 in gifts and loans, including a Rolex for him, a ballgown for his wife, and tens of thousands of dollars in cash.

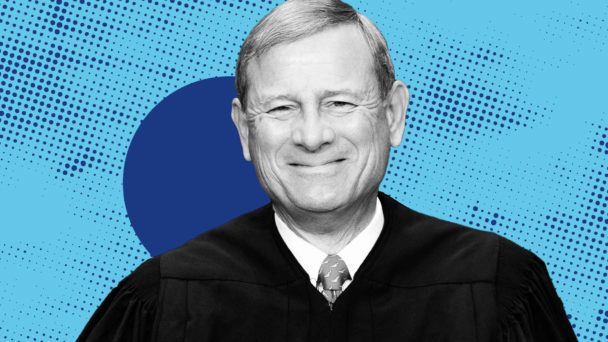

The McDonnells were convicted in 2014 under federal bribery statutes that make it a felony for officials to take “official action” in exchange for money, campaign contributions, or anything else of value. Two years later, the Supreme Court unanimously vacated those convictions in McDonnell v. United States. “Setting up a meeting, calling another public official, or hosting an event does not, standing alone, qualify as an official act,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts for the majority. By focusing narrowly on the possibility of overzealous prosecutors chilling interactions between public officials and their constituents, the Court ignored the reality of public officials putting the government up for sale.

The Court’s second blow to safeguards against public corruption came when it overturned the convictions of William Baroni, Jr., and Bridget Kelly, two former aides to New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie who orchestrated the mother of all traffic jams in Fort Lee, New Jersey. The busiest bridge in the world runs between Fort Lee and Manhattan, and in 2013, when the mayor of Fort Lee decided not to endorse Christie for reelection, Baldoni and Kelly retaliated by cutting three lanes down to one without notice. The four-day shutdown kept paramedics from reaching patients, police from searching for a missing four-year-old, and children from getting to school. Afterwards, Baldoni and Kelly crafted a cover story about shutting down the lanes for a traffic study, and directed engineers to collect useless data to make the story more credible.

Baldoni and Kelly were convicted in 2014 under federal statutes that make it a crime to defraud a federal organization. But again, the Supreme Court unanimously reversed in Kelly v. United States. “Not every corrupt act by state or local officials is a federal crime,” wrote Justice Elena Kagan, who went on to explain that officials violate the law when the “object of the fraud” is money or property; because toll lane realignment is “an exercise of regulatory power,” she continued, it didn’t qualify. By limiting the application of the law to cases where officials are specifically trying to enrich themselves, the Court immunized a wide range of unscrupulous behavior.

(Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

From 2011 to 2016, Joseph Percoco served as New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s executive deputy secretary—except for an eight-month stint in 2014, when he managed Cuomo’s reelection campaign. During the period he worked for Candidate Cuomo, as opposed to Governor Cuomo, Percoco also agreed to help a real estate developer in his dealings with a state agency, Empire State Development. ESD required the developer to enter into a “labor peace agreement” with local unions in order to receive state funding, and the developer wanted the funds without the agreement. So, he gave Percoco $35,000. In exchange, Percoco called an ESD official and urged him to drop the requirement. Percoco resumed working in the Governor’s office a few days later.

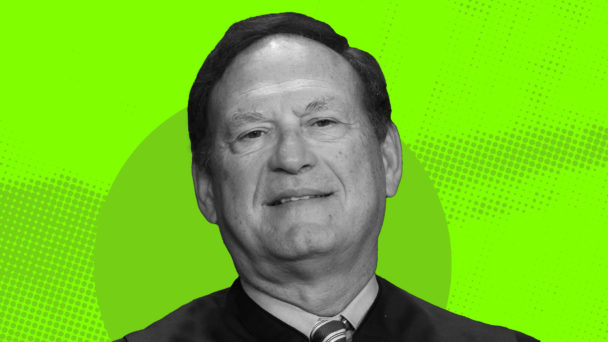

Percoco was convicted in 2018 of violating a federal law that makes it a crime to defraud the public of “honest services.” In 2023, the Court reversed that conviction in Percoco v. United States. Writing for the unanimous Court, Justice Samuel Alito explained the trial court wrongly implied to the jury that private citizens owe honest services to the public whenever their “clout exceeds some ill-defined threshold.” The Court declined, though, to give that threshold any definition, instead leaving prosecutors and courts without guidance on how they could hold corrupt public officials to account.

Finally, the Court came to the rescue of James Snyder, the former mayor of Portage, Indiana. After Snyder steered a seven-figure city contract to a truck company, he asked the company for money to pay off his tax debt and cover holiday expenses. The company obliged with a $13,000 check. Snyder was convicted in 2021 under a federal statute that makes it a crime for officials to “corruptly” solicit or accept “anything of value” while “intending to be influenced or rewarded.”

The Court—you guessed it—overturned that conviction last year in Snyder v. United States. Unlike the previous decisions, this case wasn’t unanimous, but crooked officials still had six justices on their side. The law prohibits bribes, explained Justice Brett Kavanaugh, which he defined as “payments made or agreed to before an official act in order to influence the official with respect to that future official act.” But it does not prohibit gratuities, which he described as “payments made to an official after an official act as a token of appreciation.” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson sharply criticized the Court’s legal carveout for tip jars: “Dictionary definitions confirm what common sense tells us about what it means to be rewarded,” she wrote.

The upshot of all this is that the Supreme Court is happy to excuse basically all corruption unless an official is caught with a bag labeled MONEY FROM BRIBES. Its jurisprudence has weakened key federal guardrails that are supposed to keep governments honest. Without these nationwide protections, states like New Jersey are struggling on their own.