Ten years ago, hedge fund manager and right-wing talk radio host George Jarkesy found himself on the bad side of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which Congress created in the wake of the Great Depression to enforce securities laws and protect the public against market manipulation. Conservatives, famously fond of both markets and manipulation, are not the SEC’s biggest fans. And the conservative-packed Supreme Court is now prepared to use Jarkesy’s case to take down the agency’s power to do its job.

Jarkesy got on the SEC’s radar by lying to his fund’s investors, helping to swindle them out of over a million dollars. The SEC did an investigation and gave its evidence to an administrative law judge, who after a hearing ordered Jarkesy to give up the ill-gotten profits and pay a fine. Jarkesy appealed, petitioning for his case to be reviewed by the Fifth Circuit—a federal appeals court widely recognized as right-wing crazytown—and argued that the SEC’s whole adjudicatory process was unconstitutional.

This goes beyond a challenge to the results of the SEC hearing; Jarkesy challenged the SEC’s ability to have the hearing at all. Jarkesy instead claimed that under the Seventh Amendment, which protects the right to a jury trial in civil matters, the case against him had to be resolved by a jury, not an administrative law judge. This is sort of like arguing that you don’t have to pay your overdue library book fines unless the librarian gets the entire neighborhood’s approval first.

Jarkesy went to the right place: The Fifth Circuit issued an astonishingly broad ruling in his favor and determined on multiple constitutional grounds that the SEC doesn’t have the power—and, beyond that, that Congress can’t give it the power—to adjudicate cases in the usual way. Instead, the Fifth Circuit agreed that SEC enforcement actions that seek civil penalties have to go through jury trials in federal court. Relying on jury trials would make SEC enforcement actions much more costly and cumbersome, leading to fewer prosecutions for securities fraud and, thus, more fraudsters defrauding the American people. The SEC appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which heard the case, SEC v. Jarkesy, on Wednesday.

Oral argument did not bode well for the future of the SEC and the millions of people it protects from the schemes of money-grubbing millionaires. Jarkesy’s counsel, S. Michael McColloch, argued that modern securities fraud charges are basically the same as common law actions recognized in the courts of England in 1791, when the Seventh Amendment was ratified. Justice Neil Gorsuch asked McCollocuh to compare claims then and now, and seemed satisfied with the response. “Those elements all match up,” Gorsuch said.

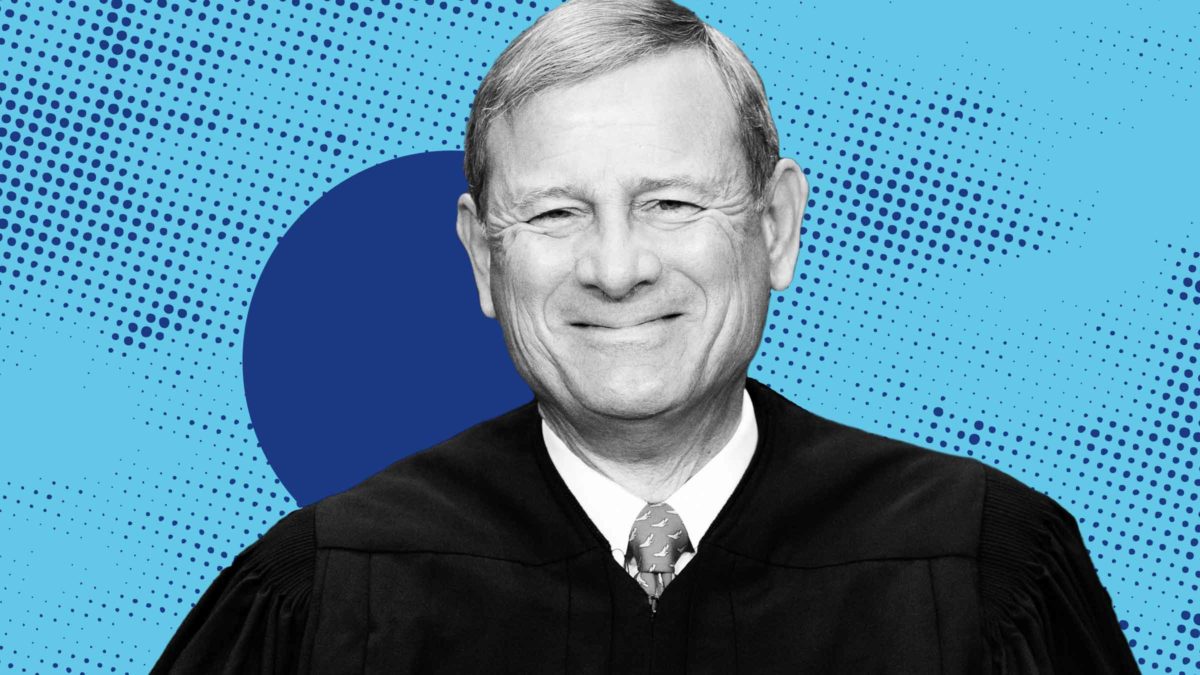

Chief Justice John Roberts also framed the case as a chance for the Court to protect the sacred right to a jury trial from falling before the administrative state. “It does seem to me to be curious that, and unlike most constitutional rights, that you have that right until the government decides that they don’t want you to have it,” he said, “That doesn’t seem to me the way the Constitution normally works.” (Roe v. Wade could not be reached for comment.)

When you see a particularly clever securities fraud scheme (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The liberal justices, in contrast, found Jarkesy’s reasoning absurd. Justice Elena Kagan pointed out that Congress enacted securities laws in response to modern financial crises specifically because founding-era common law actions were insufficient to prevent widespread harm. “When you say, well, we should go back to the common law suits that were brought 200 years ago in the courts of Westminster, is Congress’s judgment—after the Depression, after the Savings and Loan Crisis, after the Great Recession—is Congress’s judgment that more powers were needed within an administrative agency entitled to no respect?” she asked.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson also struggled to make sense of Jarkesy’s proposed standard, which represents a break from established law. Modern financial regulations created new statutory duties that bear no resemblance to two-century-old common law claims, she pointed out—here, among others, the duty “not to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud in the context of securities transactions.” And “if it’s a new statutory duty,” said Jackson, “we’ve held for forever that Congress can assign it to the administrative agency.” In other words, perhaps Congress can address new problems in ways that did not exist in 1791.

The outcome in SEC v. Jarkesy may exacerbate those problems. The National Treasury Employees Union, which represents employees in 35 federal agencies including the SEC, explained in an amicus brief that affirming the Fifth Circuit’s decision would “dramatically reduce the SEC’s ability to fulfill its statutory mandate. And as the law professor Noah Rosenblum highlighted in The Atlantic on Monday, “one needs only to examine the rampant fraud, contagion, and meltdown in crypto markets last year to see what an unregulated securities market looks like.” Imagine—your retirement fund, all invested in NFT pictures of monkeys!

The country’s financial stability is not the only thing at stake. Many agencies function in a similar manner to the SEC, so a ruling in Jarkesy’s favor could destabilize much of the way the government enforces regulations to protect our environment, our food safety, our workplace conditions, and more. On Wednesday, social media giant Meta (formerly Facebook) filed a lawsuit challenging the enforcement powers of the Federal Trade Commission as unconstitutional, too. Challenges to the FTC’s authority aren’t new, but after oral argument in SEC v. Jarkesy, Meta is feeling pretty good about its chances of succeeding this time.

The conservative legal movement has been preparing for an opportunity like this for a long time, nominating judges who are hostile to administrative agencies and favor deregulation, of financial markets and everything else. And several such judges now sit on the Supreme Court. Conservatives pretend as if this case is about whether the government can be judge, jury, and executioner of poor vulnerable millionaires. But really, it’s about whether the government can protect the public from the whims of the uber-wealthy. And the conservative Supreme Court is much more interested in protecting the uber-wealthy from the public.