On Wednesday, the South Carolina Supreme Court decided that it has no power to protect Black voters from partisan gerrymandering, dismissing a challenge to the state’s congressional district map as a “nonjusticiable political question” in a 5-0 opinion. The only people with the legal power to un-gerrymander the state, it seems, are the Republican lawmakers who gerrymandered it in the first place.

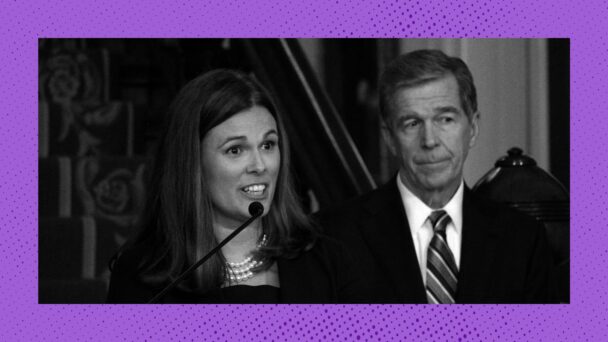

In 2021, South Carolina’s Republican-controlled legislature adopted maps that moved over 30,000 Black residents out of the state’s first congressional district, reducing its Black population to 17 percent—the precise amount necessary, per GOP analyses of partisan voting patterns, to keep Black voters from threatening Republican dominance in District 1, which is currently represented by Republican Nancy Mace. This little maneuver is likely enough to prevent the state’s Democrats from competing to oust her, and to pick up a seat in Congress.

In 2023, a three-judge panel of South Carolina’s federal district court unanimously struck down this ambitiously racist map as unconstitutional. But in 2024, the Supreme Court reversed that judgment, concluding that the state didn’t discriminate against the voters because they were Black, but because they were Democrats. As a practical matter, this distinction doesn’t mean much—either way, lawmakers are discriminating against Black people, who overwhelmingly vote for Democrats. Still, under the Supreme Court’s precedent, the map presented a political question for state legislatures and state courts to solve, not a constitutional question for federal courts to solve.

So, a couple months later, South Carolina voters filed a new lawsuit in state court, challenging the map as an “extreme partisan gerrymander” that violates several provisions of the state constitution. But on Wednesday, the South Carolina Supreme Court batted away that challenge, too, as an unanswerable political question. As a result, South Carolina legislators are free to continue picking their voters, and South Carolina voters have no real shot at picking their legislators.

Much of the South Carolina court’s opinion is spent recounting the rationale of the U.S. Supreme Court in Rucho v. Common Cause, the 2019 case in which the Court decided that there is no constitutional problem with politicians manipulating district lines to keep themselves in power. Justice George James wrote that Rucho held that “federal law does not furnish judicially discernible and manageable standards for reviewing claims of partisan gerrymandering (as opposed to racial gerrymandering),” thus rendering such claims “nonjusticiable under the United States Constitution.” James wrote that the same is true at the state level: “There are no constitutional provisions or statutes that pertain to, prohibit, or limit partisan gerrymandering in the congressional redistricting process in South Carolina,” he said.

So, the South Carolina Supreme Court reached the same conclusion the U.S. Supreme Court did: “Partisan gerrymandering claims present a nonjusticiable political question.”

When the U.S. Supreme Court decided Rucho, Chief Justice John Roberts argued for the majority that he was not dooming the public to rule by unrepresentative government. “Our conclusion does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering. Nor does our conclusion condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void,” said Roberts. As consolation, Roberts pointed to the state supreme court in Florida, which struck down an electoral map in 2015 as violating the Fair Districts Amendment of the state constitution. “Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply,” Roberts said.

(Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

In light of the South Carolina Supreme Court decision, Roberts’s gesture looks even emptier. Today, at least 13 states explicitly address partisan gerrymandering in their constitutions or statutes, but South Carolina is now the fourth state since Rucho to decide that partisan gerrymandering is nonjusticiable, following New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Kansas.

At the same time, Rucho has encouraged Republican legislatures to swing for the antidemocratic fences. South Carolina’s Senate Majority Leader, Republican Shane Massey, outright told reporters that they “knew” their gerrymandered map was “something that we could do” because of “the rules that the Supreme Court set out.” After the state court’s decision, the South Carolina’s Republican Senate Caucus boasted on Twitter: “While numerous red states hurry to undergo mid-decade redistricting, South Carolina rests easy knowing Republican Senators finished the job following the 2020 census.”

In a brief concurring opinion in the South Carolina case, Chief Justice John Kittredge lamented the widespread undemocratic impact of Roberts’s opinion. “Following Rucho‘s elimination of any possibility of a federal constitutional violation, state legislatures became emboldened,” he said. And since state laws are often insufficient to deter gerrymandering, he continued, district maps that “may, indeed, be in line with each respective state’s constitution and laws” could still “collectively have the effect of diminishing our constitutional republic as a whole.”

The ongoing race to wipe out minority political parties, Kittredge concluded, is “a troubling prospect for those who adhere to our nation’s founding principle that the People are sovereign.”

Fundamental rights like voting in free and fair elections should not depend on what state one happens to live in. But that is the current legal landscape the Supreme Court created. And South Carolina voters are now suffering the consequences.