On Monday, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case of someone you’d probably forgotten about until right now: Kim Davis, the former Kentucky county clerk who became a national news story in 2015 for her steadfast refusal to issue a marriage license to a same-sex couple. After a federal judge found her in contempt of court, she eventually chose to spend several days in jail rather than simply do her job, because for reactionaries who hold public office, there is no greater indignity than having to serve people you do not personally like.

Davis’s case, Davis v. Ermold, is about her appeal of a jury award of damages and legal fees to the two men she turned away. Yet in her petition for review, she also asked the Court to overturn the 2015 decision that started this entire controversy and briefly made Davis infamous enough to become the subject of a Saturday Night Live skit: Obergefell v. Hodges, in which the Court first recognized a constitutional right to marriage equality. Obergefell, Davis’s lawyers argued, is “egregiously wrong,” and a “mistake” that “must be corrected.”

I understand why Davis decided to try. Today’s Court, controlled by a six-justice conservative supermajority, is considerably further to the right than the Court that decided Obergefell a decade ago. Three of the Obergefell dissenters are still on the bench, and the author of the majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy, retired in 2018. In 2022, the Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned its opinion in Roe v. Wade, which provided part of the doctrinal foundation for Obergefell. In a concurring opinion in Dobbs, Justice Clarence Thomas explicitly called on the Court to overturn Obergefell, too, which he described as a “demonstrably erroneous” case of “judicial policymaking.”

Unfortunately for Davis, the changes in the composition of the Court did not make a difference in the outcome of her case, as the justices turned Davis away without any noted dissents. Even Thomas, whose contempt for Obergefell is a matter of public record, decided that this was not an occasion to repeat himself any further.

As evidenced by the five decades leading up to Dobbs, the conservative legal movement is not exactly known for taking no for an answer. But Davis’s odds were always long here. In the world of right-wing legal organizations that typically jockey with one another for cases like this one, her lawyers are nobodies. For technical reasons not worth detailing here, her appeal would have made for a messy vehicle for overturning Obergefell even if the justices were inclined to try it. There are political hurdles, too: Legal protections for same-sex marriage are very popular, and even some justices who might otherwise be skeptical of marriage equality have acknowledged the real-world impracticality of pulling the rug out from under millions of couples who have relied and continue to rely on Obergefell’s promise.

That said, many outlets breathlessly covered Davis’s cert petition anyway—a choice you can attribute to some combination of lingering name recognition, the stakes of her request, and the media’s cynical but unfortunately correct understanding that in a legal news environment in which reactionaries are winning everything all the time, some sequences of words will reliably get fear-induced clicks. For the same reason, Monday’s order earned far more headlines than denied cert petitions usually do; many connoted a sigh of relief and/or downplayed the notion that Obergefell was ever in danger in the first place. One professor at Notre Dame Law School took the chance to do a little free PR for the Court, arguing that coverage of Davis’s case “tells us more about the ongoing campaign to stir up public feeling regarding the Court than it does about live constitutional questions.”

Two weeks earlier and 1,500 miles away, the Supreme Court of Texas was in a very different headspace. On October 24, that court decided that Texas justices of the peace do not violate their code of conduct by declining to perform same-sex wedding ceremonies based on their “sincerely held religious beliefs.” All eight active Texas Supreme Court justices, all of whom were appointed by Republican governors, signed the ruling, which will now appear as an official comment to Canon 4 of the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct.

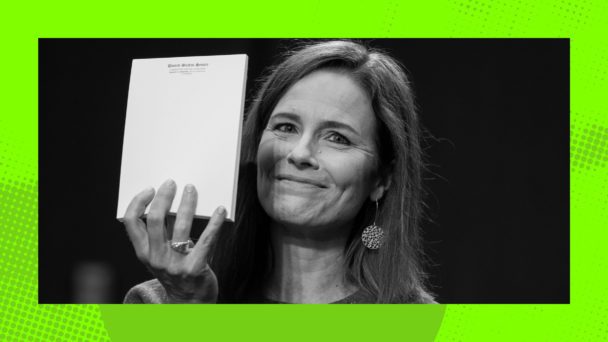

Davis after her release from jail, September 2015 (Photo by Ty Wright/Getty Images)

This case started six years ago, when the state Commission on Judicial Conduct issued a warning to one such justice of the peace, Dianne Hensley, on the grounds that her willingness to perform weddings for opposite-sex couples but not same-sex couples cast doubt on her impartiality as a judge. Hensley sued, arguing that the reprimand violated her rights under the Texas Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Other officials in Texas began asserting similar claims, and although the Texas Supreme Court’s ruling does not resolve the legal proceedings once and for all, the challengers are celebrating anyway. “Every judge in Texas will enjoy the freedom Judge Hensley has fought so hard for,” her lawyer said afterwards.

Justices of the peace are not the only people who can perform weddings in Texas; the court’s decision will not wipe out the ability of same-sex couples to marry overnight. But the fact that the decision will make marrying more challenging for at least some same-sex couples is enough. When the right to marry is contingent upon the willingness of people in power to treat everyone who comes before them with dignity and respect, it is not a right to marry at all.

This result in Texas, the country’s second-most populous state, reveals much more about the future of civil rights for LGBTQ people than Kim Davis’s 15 minutes of fame finally, mercifully coming to a close. Anti-gay activists shifted their legal strategy after Obergefell, pushing for laws and policies that qualify the right the Court’s decision protects in the name of religious freedom. Lawmakers in Arkansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee have all enacted laws that allow state and local officials to decline to marry couples of whom they disapprove. Some states acted in the immediate aftermath of Obergefell, but others have done so more recently, perhaps encouraged by the output of a six-justice conservative supermajority whose members have made clear that on their view of the First Amendment, antidiscrimination laws must bow to the private beliefs of bigots who do not feel like following them.

Even Davis, despite her near-unbroken string of court losses and status as a national laughingstock, eventually eked out something of a policy win on this front. In November 2015, Kentucky Republican Governor Matt Bevin signed an executive order that removed county clerks’ names from all marriage licenses, for straight and gay couples alike. As a result, elected officials in Davis’s shoes still have to issue a marriage license to a same-sex couple that asks, but they are spared the indignity of having to put their names on it.

It is of course good that Obergefell survived Kim Davis’s clumsy last-ditch effort to destroy it. But a legal guarantee of equal treatment is only as strong as a public official’s legal obligation to recognize it. In Texas, people like Kim Davis don’t need the Supreme Court’s help. They’re getting their way already.