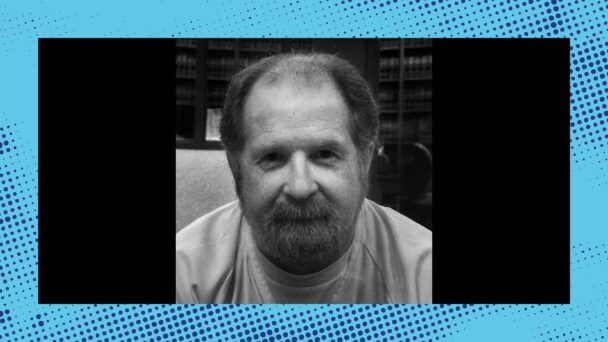

When Joseph Clifton Smith, an Alabama man who was convicted of murder in 1998, was in third grade, he needed help reading at a first-grade level. His teachers ordered further testing, which yielded an IQ score of 75, indicating that he was “functioning in the Borderline range of measured intelligence.” After more testing the following year, Smith was placed in a learning-disability class. When he reached seventh grade, his school moved him into “educable mentally retarded” classes—a term the state used in the 1970s to classify students with IQ scores below 75 and documented deficits in adaptive behavior. After failing the seventh and eighth grades, Smith dropped out of school altogether.

At the time of his crime, when Smith was 28 years old, he scored a 72 on an IQ test, placing him at the third percentile of the general population. Trial evidence also showed that he read at about a fourth-grade level, spelled at a third-grade level, and did arithmetic at a kindergarten level. An Alabama trial court sentenced Smith to death in 1999.

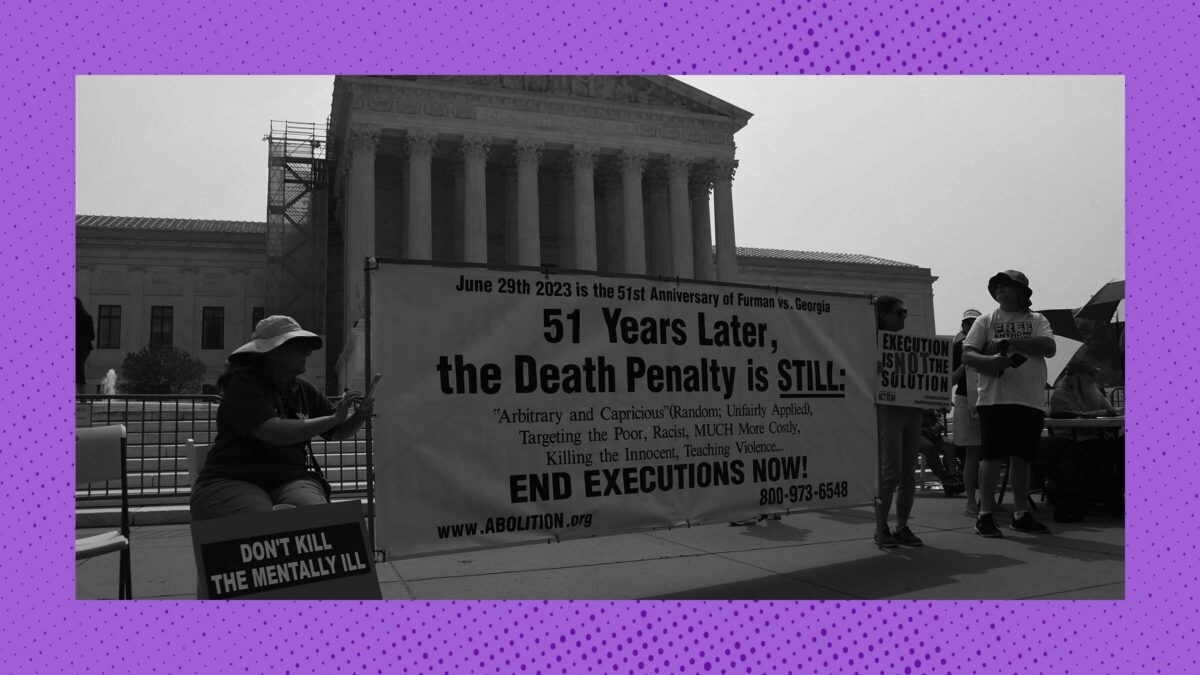

In 2002, though, the Supreme Court held that executing an intellectually disabled person is unconstitutional. The Eighth Amendment prohibits the imposition of certain “excessive” punishments, as well as the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments.” And in Atkins v. Virginia, the Supreme Court concluded that the death penalty is “excessive” in light of intellectually disabled people’s diminished culpability, as well as the country’s “evolving standards of decency.” Furthermore, the Court noted that the practice had “become truly unusual”: In the decade or so prior to Atkins, only five states executed people known to have an IQ less than 70.

After Atkins, Smith successfully sought an evidentiary hearing on his intellectual functioning, and a federal court concluded that “Smith is intellectually disabled and cannot constitutionally be executed.” Alabama appealed, but the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed. The state has now appealed those decisions to the Supreme Court in Hamm v. Smith.

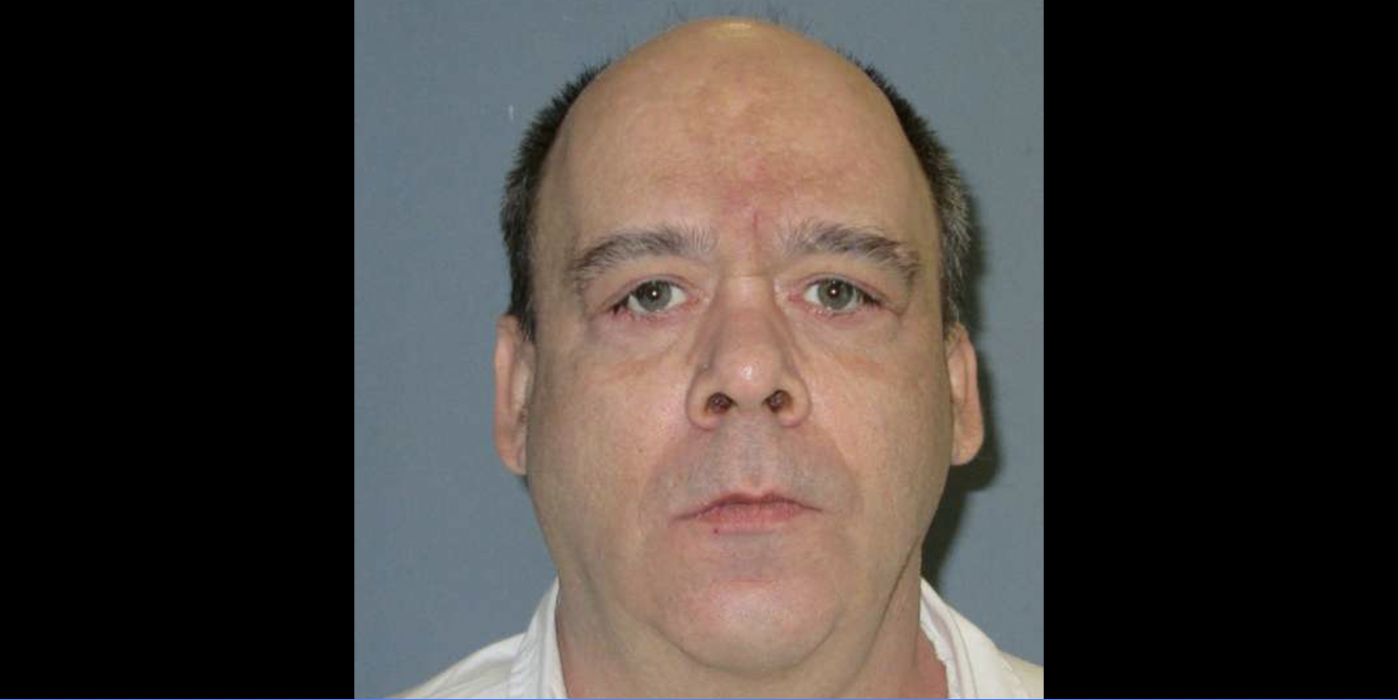

Image via Alabama Department of Corrections

During oral argument on Wednesday, Alabama Principal Deputy Solicitor General Robert Overing agreed that “Atkins created an exception for offenders known to be intellectually disabled.” But, he argued, Smith’s history of IQ scores over the years shows that he is not actually disabled. “He didn’t come close to proving an IQ of 70 or below with scores of 75, 74, 72, 78, and 74,” Overing said.

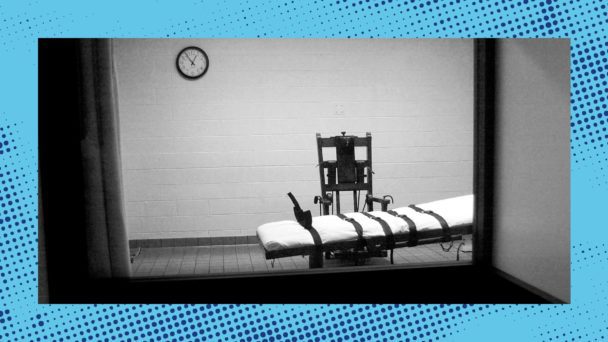

Crucially, Atkins did not say that an IQ score of 70 or above definitively means someone is not disabled. And in subsequent cases about intellectual disability and the death penalty, the Supreme Court clarified that “intellectual disability is a condition, not a number.” Yet Alabama essentially argued that states should be able to treat an IQ of 70 as a numerical can-kill cutoff point. Now, the Supreme Court must enter into this ghoulish debate and determine whether Joseph Smith is too disabled to execute, or, put differently, just disabled enough to allow to live.

On Wednesday, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pressed Overing about Alabama’s reliance on Smith’s IQ scores to the exclusion of all else—including the margin for error on those tests—when “the words ‘IQ score under 70’ do not appear” in the Court’s standard, and when IQ is only one indicator of the test for intellectual disability. “What you’ve done is shift this to be all about the IQ test in a way that is not supported by our case law,” Jackson said.

There are good reasons why there shouldn’t be a bright-line legal test, too. The American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities filed an amicus brief in this case explaining that disability diagnoses reflect “clinical judgment,” not a mere “actuarial determination.” Although IQ tests may provide useful information, the association wrote, “there can be no single, mandatory empirical method” to determine whether someone is intellectually disabled. In another amicus brief, a coalition of psychological and psychiatric associations emphasized that IQ tests can be probative but are not dispositive, and that professionals must make their diagnoses “after undertaking a holistic assessment of all relevant data and applying their clinical judgment.”

Predictably, Justice Samuel Alito worried that more individualized determinations would lead to more people escaping the electric chair. He warned that if the Court decides that “everything is up for grabs in every case” about the disability status of people on death row, then in future cases, “both sides can bring in experts to testify about the person’s intellectual disability or lack of intellectual disability, and every trier of fact is going to decide that on an individualized basis.” According to Alito, one of the touchstones of the Court’s death penalty jurisprudence is “greater consistency and predictability,” which is a polite way of saying that the Court has often made it a priority to see that states carry out as many executions as they wish.

The Constitution’s aims are different, though: As the Court held in Atkins, the Constitution does not permit states to sentence intellectually disabled people to death. Smith is an opportunity for the Court to reaffirm that simple rule. States like Alabama are trying to skirt the rules instead.