As a non-lawyer—I teach middle school math in the rural South—I often read Supreme Court cases with the same look on my face as the average student in one of my tougher algebra lessons. It is rare that a case speaks to me regarding, or has an impact on, my profession. Mahmoud v. Taylor does both of those things, in all the wrong ways.

Mahmoud, which the Court decided earlier this summer, centers on a group of parents suing a Maryland school district over a small selection of children’s books that portrayed LGBTQ characters, on the grounds that exposing their children to such material would burden the parents’ free religious exercise. The Court split 6-3 along party lines, as probably the whole country expected. The majority opinion from Justice Samuel Alito and the dissenting opinion from Justice Sonia Sotomayor argue about the meaning of the Free Exercise Clause, parse the case law on which the majority draws to justify its conclusion, and conduct rudimentary literary analyses of some of the books in question. (As usual, in a concurrence, Justice Clarence Thomas has more to say that’s too bonkers for any of his fellow conservatives to join).

But the impact that a case like Mahmoud has on my profession cannot be found in constitutional vagaries or arguments about children’s books. As a heavily left-leaning person in a position of influence over the children of very conservative parents, it was already difficult to teach in ways that my students can reconcile with what they have been taught before they enter my classroom. In my view, the primary consequence that Mahmoud imposes on teachers is that we now have far greater reason to believe we will be targeted on an individual level by bad-faith actors—from parents to school administrators to members of the legal profession—for how we incorporate our values into our teaching.

During the fall of 2020, I discovered a Black artist who had written a socially conscious song about voting and government, and the impact on Black communities in particular. I played it for my students during one of our remote classes (my school was remote due to the COVID-19 pandemic at the time) as a short break from the drudgery of learning proportions over Zoom, and as a way to incorporate a Black voice speaking on social issues to my mostly white students. One parent objected strongly to the song, which was not explicit or inappropriate, and complained about it to my principal. My principal responded to this parent’s claims that my teaching was going against their values and beliefs in a way that ended the discussion before it had the potential to become, from what he told me, at least a board-level investigation into my conduct.

At the time, I saw this incident and this parent as an anomaly. But over time, as similar incidents piled up in my area and the nation at large, I began to see shifts in both the broader political culture and also my position in it as a teacher.

Recently, I learned of one teacher whose experience dwarfs my own: Sarah Imana, formerly the sixth-grade history teacher at Lewis and Clark Middle School in Meridian, Idaho. I say “formerly” not because the district reassigned Imana due to staffing shortages or budget cuts, or because Imana voluntarily sought a career change that promised more money, benefits, and respect. It is because of something much, much, stupider: school administrators’ concerns over inclusive classroom posters that hung in Imana’s classroom. One read, “Everyone is Welcome Here,” and one affirmed all students as “welcome, important, accepted, respected, encouraged, valued, [and] equal” in (gasp) rainbow colors.

In March, Imana’s school administrators decided that the posters were too controversial, under a district policy requiring “content-neutral” decorations, and ordered her to remove them. A representative from the district admitted that “the political environment ebbs and flows, and what might be controversial now might not have been controversial three, six, nine months ago”—tacitly admitting that what is “controversial” is in part determined by who has the power to promote normative messages and values about society. Having seen the interpretation of district policy turn against her based on the current cultural and political climate, Imana resigned her teaching position after a drawn-out battle.

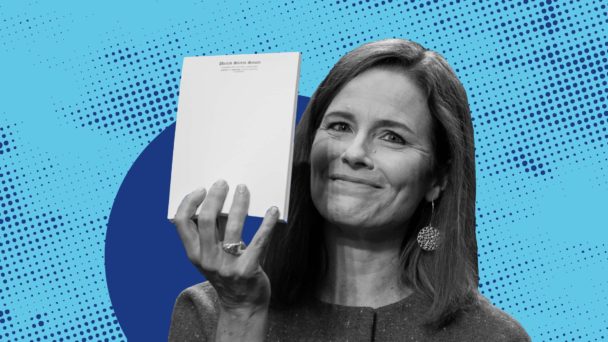

(Photo by OLIVER CONTRERAS/AFP via Getty Images)

A few months later, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Wood v. Florida Department of Education that Katie Wood, a transgender woman, cannot use her preferred pronouns and honorifics in her position as a public school teacher in Florida, and cannot ask her students to do the same. The Eleventh Circuit’s panel opinion cites extensively to Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, a 2022 Supreme Court case which held that a football coach leading his team in public prayers on the football field immediately after a game is protected religious expression under the First Amendment.

One particular line from Kennedy used by the majority in Wood is relevant here: The Wood panel stated that teachers are “paid in part to speak on the government’s behalf and convey its intended messages,” interpolating this quote in a ruling against a trans teacher in a case that has absolutely nothing to do with religion. This is the conservative legal ecosystem at work: using religion as a starting point that broadly appeals to the conservative base, and moving towards the ultimate objective of social control by conservatives, particularly over public schools and the teachers they employ.

The deeper issue highlighted by decisions like Wood and Kennedy is just how far removed federal judges are from the experiences of the people whose lives their decisions govern. If you want to be laughed at—or reminded of how it feels to be on the receiving end of a “teacher look”—ask any teacher if their favorite part of the job is “speaking on the government’s behalf.”

No teacher goes into, or stays in, our profession because of what we have to teach. We do it for the relationships we can build and the positive influence we can have—with individual children, families, coworkers, and the community at large. Even more than the relationships in which we are directly involved, I would argue that the most important relationships we build are those interpersonal relationships between the children in our care, which we get to foster and nurture as we oversee their development as individuals. This serves the truly important work of preparing children to live in society as responsible, ethical, and empathetic citizens. It is also what makes our profession dangerous to the conservative movement.

Mahmoud will have consequences for schools and teachers that are much broader than one teacher’s use of her preferred pronouns. Sotomayor’s dissent rightly discusses some of the underlying effects of the majority opinion. She states that in school, children do not learn “the teachings of a particular faith, but a range of concepts and views that reflect our entire society.” She goes on to describe the chilling effect of the Court’s holding in Mahmoud on school districts and their endeavors to meet this lofty goal: “administrative burdens,” “classroom disruptions and absences,” and “costly litigation over opt-outs” from curricula and lessons.

While Sotomayor briefly mentions the case’s logistical and administrative impact on teachers, she does not discuss the place of the majority opinion in the broader culture war that her conservative colleagues are waging, or its impact on teachers like me. Under this holding, parents of children in Imani’s or Wood’s classes could claim that Imani’s posters—or Wood’s very existence and identity as a transgender woman—burden their ability to exercise their faith. Every teacher you know has at least one story about a nightmare parent, and the conservative supermajority has given those parents more avenues to go after not just curricula or books, but teachers as well. (Theoretically, the parent who complained about me could claim to be a pre-1978 Mormon who believes Black skin to be a sign of God’s curse as a way to ensure her complaint would reach the school board.)

The right has made schools battlefields in the modern culture war. Teachers didn’t enlist to fight it, but we are on the front lines anyway.

Until I read Mahmoud v. Taylor, I had not seen such a personally relevant example of how out of touch the justices are with the people they rule over, or how their decisions impact people they do not discuss within their writing. The justices can focus very narrowly on, for example, parents’ rights and children’s books because they don’t have any incentive or experience to motivate them to see broader impacts on people like teachers.

I am not at all surprised that the justices, who do little more than give lectures and sit on panels, do not speak with any knowledge of the kind of teaching that requires convincing 13-year-olds to stop awkwardly flirting with each other, or laughing at “the funny number” [Ed. note: 69] long enough to learn what a function is. The level of power and social isolation we as a society have vested in the judiciary, and the decades-long exploitation thereof by the conservative legal movement, has resulted in a legal system that gives bad actors the ability to prevent a transgender teacher from using her own pronouns on the job, while well-meaning judges like Sotomayor feel the need to argue on the terms set by those bad actors—missing the real-world stakes in the process.

We are entering a time in which far-right conservatives treat teaching progressive values as a dereliction of the teacher’s primary duty to promote the views that are currently in power, and in which public schools as a whole are such a threat to those in power that they are trying to bleed schools dry. It is a tragedy that even the liberal wing of the Court cannot see this clearly.