In December 2020, Sara Fraga began work as a merchandiser at Premium Retail Services, Inc., a logistics company that works with retailers to increase product sales. Fraga was responsible for in-store product displays, ensuring that consumers would see and buy products like sunglasses, shampoo, and more.

In May 2021, she filed a wage theft class action lawsuit against the company, alleging that she and other workers were only paid for the hours they spent at individual stores, not the time they were required to put in at home and on the road. According to Fraga, this meant that the time she spent sorting products, repackaging displays, and driving to five or more stores a day—stores scattered across Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York—was all work that she was required to do without compensation.

Was Fraga correct that the company, by shorting its employees for hours of pay every week, was stealing from them? Unfortunately, we may never know. In December 2023, Judge William Young of the District of Massachusetts ruled that Fraga was required to arbitrate her claims, rather than bring them in open court. The key federal statute was not, as Fraga argued, the Fair Labor Standards Act, the foundational labor law that protects workers’ right to a minimum wage and overtime pay, but rather the Federal Arbitration Act, or FAA, which Congress passed back in 1925.

Arbitration is a system for resolving disputes outside of the traditional legal system. In theory, it allows two parties who have voluntarily agreed to alternative dispute resolution to avoid expensive, time-consuming entanglements with the judiciary. As legal scholars including Myriam Gilles and Imre Stephen Szalai have documented, Congress intended the FAA to ensure that, when two businesses agreed to arbitrate any future contractual disputes between them, judges would enforce that commitment in court. The FAA was a statute governing commercial contracts—of importance to the Chamber of Commerce, but with relatively little significance for the average person.

Yet in the century since its passage, judges have transformed the FAA into something that keeps millions of workers and consumers from holding businesses accountable for their wrongdoing. As a result, the law has effectuated a massive transfer of wealth from individuals to corporations, and contributed to the steady rise of unchecked corporate power. As Justice Sandra Day O’Connor put it in a 1994 opinion, the Court in its FAA jurisprudence “has abandoned all pretense of ascertaining congressional intent with respect to the Federal Arbitration Act, building instead, case by case, an edifice of its own creation.”

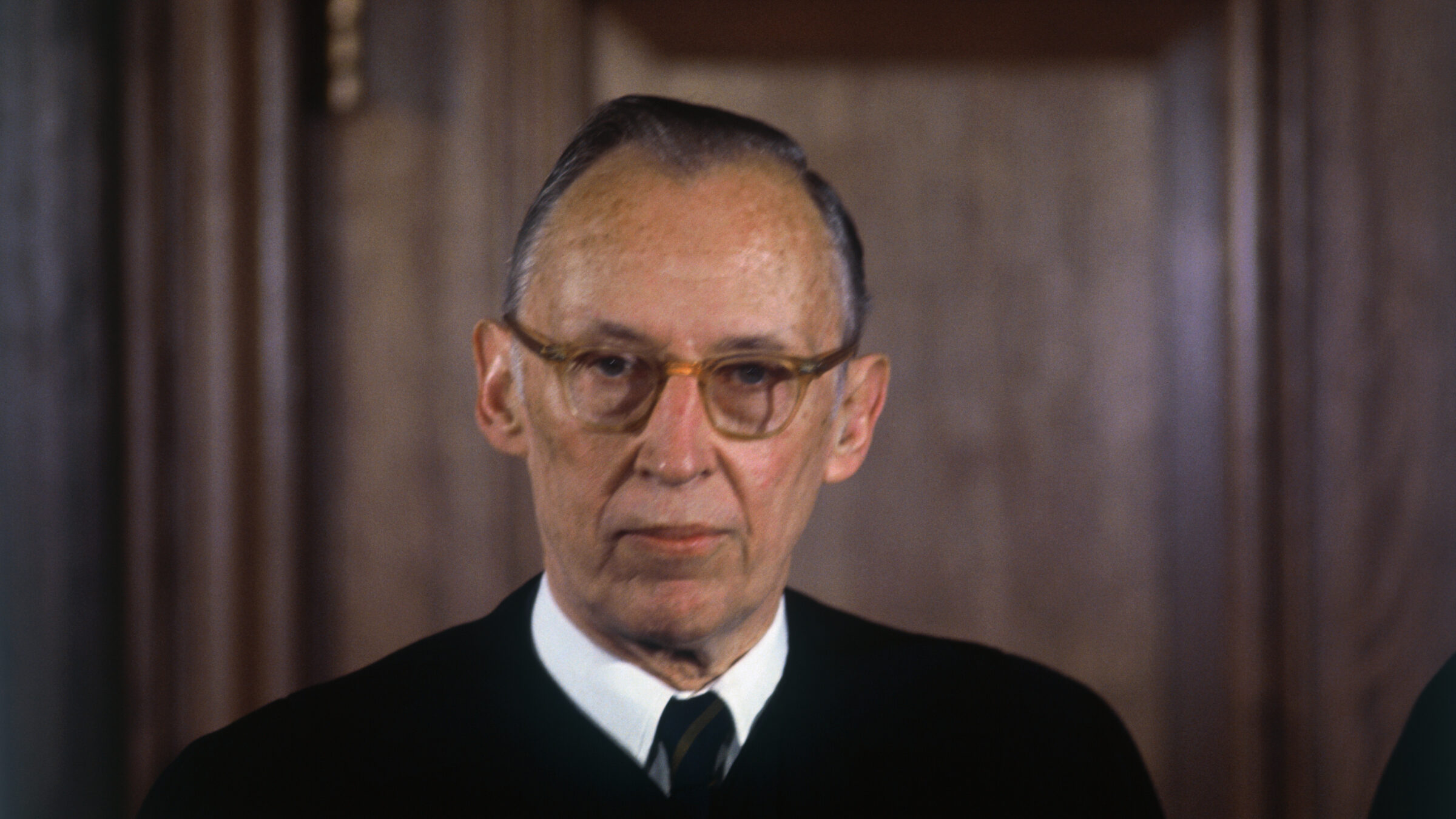

Portrait of Lewis Powell, 1972 (Getty Images / Bettmann)

The construction of that edifice began in earnest in the 1980s when, thanks to Justice Lewis Powell and his allies at the Chamber of Commerce, the Supreme Court was well on its way to becoming a reliable champion of corporate America’s interests. In 1984, the Court decided that passage of the FAA—essentially one sentence written into law 60 years earlier—meant that there existed a “national policy favoring arbitration.” From there, the judicial floodgates opened. In a 5–3 decision one year later, the Court held that the FAA covered statutory claims, not just contractual disputes, so that allegations that a company was violating the law (not just the terms of a contract) could be heard by an arbitrator rather than a judge. As Professor Paul Carrington wrote, this case helped the Court “establish[] its ‘national policy’ allowing economic predators to contract at least partially out of the system of effective private law enforcement, thereby exposing consumers, employees, small businesses, and other persons of limited economic bargaining power to a thousand wounds.”

Ten years later, in 1995, the Court went even further, holding that arbitration clauses could be enforced in consumer contracts, not just contracts between two businesses. And in 2001, the Court held that the statute applied to employment contracts, too. Together, these cases prevented swaths of legal rights from being vindicated in courtrooms, and allowed arbitrators—often hand-picked by companies they have a financial incentive to side with—to be in charge. As unaccountable as federal judges are to the people whose lives are controlled by their decisions, arbitrators are even worse.

After spending decades creating a legal regime binding people, knowingly or not, to forced arbitration, the Supreme Court turned to the work of ensuring that those people had no alternatives available to them. In 2011, a 5-4 opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia held that states couldn’t pass laws that prevent businesses from offering contracts that prohibit class-wide arbitration. As Justice Stephen Breyer pointed out in dissent, this effectively prevents consumers from holding businesses to account for widespread perpetuation of minor fraud. Picture a case in which a large company overcharged every consumer by a few dollars. Because no single customer would be able to justify the time and expense of taking this to arbitration, the company would get away with millions of dollars’ worth of fraud.

As Breyer put it in Concepcion, a case about a cell phone provider’s deceptive advertising practices: “What rational lawyer would have signed on to represent the Concepcions in litigation for the possibility of fees stemming from a $30.22 claim”?

In sum, over just a few decades, a handful of elite lawyers on the bench—aided by a few more elite lawyers in corporate law firms who argued the cases—took a statute meant to govern business-to-business disputes and turned it into an all-powerful national policy affecting workers and consumers everywhere. And as with all things the Supreme Court does, this decision to rewrite the law to value corporate bottom lines over individuals’ rights to their day in court came with no public oversight. There was no opportunity for the people to weigh in, either directly or via their elected representatives. Under the guise of deciding a series of legal cases, the Supreme Court—unelected, unaccountable actors—made a set of critical policy decisions that allow bad actors to operate with impunity, too often at the expense of women and people of color.

Of course, Congress could pass legislation, such as the Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal (FAIR) Act, to prohibit forced arbitration clauses in consumer and employment contracts. But as the Court’s history of warping the FAA’s text beyond recognition demonstrates, passing the FAIR Act alone isn’t enough to protect normal people from greedy corporations and their allies on the bench.

One way Congress could ensure that courts enforce the FAIR Act (and other statutes) as Congress intended is to create a process of streamlined congressional review of Supreme Court decisions that interpret federal statutes. As scholars including Ganesh Sitaraman have explained, such a process would enable Congress to implement legislative fixes in a fast-track process, avoiding the filibuster, hearings, amendments, and so on. If this process had existed previously, lawmakers might have used it after any number of court decisions that inappropriately expanded the FAA’s reach: Instead of having to go through the process of trying (and probably failing) to pass new legislation every time the Court gets something wrong, this mechanism would allow Congress to act swiftly to preserve its core policymaking role in our democracy.

The history of the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Federal Arbitration Act should serve as a cautionary tale about what happens when Congress lets the judiciary—the branch of government that is the least democratic and most easily captured by corporate and partisan interests—have too much power. Allowing for fast-track review of Supreme Court decisions is one way for Congress to serve as a true check on the Court’s relentless power grab—and help people like Sara Fraga hold their stealing employers to account.