Few ideas unite the right’s diverse array of grifters, bigots, and Elon Musk fanboys like the unfailing belief that someone, somewhere is violating their fundamental Right to Post. This week, the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority at last had the chance to do something about this perpetual free speech emergency. On Tuesday, the justices heard oral argument in Gonzalez v. Google, a case about Section 230, a once-obscure provision of federal law that Republicans now invoke in Pavlovian fashion whenever one of their transphobic screeds earns, in their estimation, an insufficient number of retweets.

The short version of Section 230, which Congress passed in 1996, is that it protects platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Google from liability for the content their users post. It also frees platforms to moderate content as they see fit, a crucial decision that allowed Internet companies to grow and operate without fear of devastating liability. For this reason, Section 230 is sometimes referred to as the “26 words that created the Internet.”

More recently, however, the freedom to moderate has prompted conservatives poisoned by years of mainlining conspiracy theories to conclude that a shadowy cabal of Silicon Valley overlords is abusing this privilege to censor their political speech. During his pre-insurrection Twitter heyday, President Donald Trump often railed against the injustices wrought by Section 230, threatening to veto a key spending bill unless Congress embedded a repeal provision in it. Other Republicans have proposed legislation to peel back Section 230’s protections, courageously taking aim at the scourge of right-wing YouTubers unable to monetize clips of themselves vandalizing Pride displays in Target.

Against this backdrop, First Amendment experts were understandably nervous about Gonzalez’s potential to break the Internet as we know it. But a “cancel cancel-culture” counterrevolution now seems unlikely, because oral argument made abundantly clear that the justices are in way, way over their heads. At one point, Justice Samuel Alito admitted that he was “completely confused”; later, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson described herself as “thoroughly confused.” Justice Clarence Thomas was merely “confused,” no modifier, which might have been the most optimistic self-assessment of anyone on the bench that day. Justice Elena Kagan earned chuckles when she described the justices as “not, like, the nine greatest experts on the Internet,” which felt like a generous understatement.

“We’re a Court. We really don’t know about these things. These are not, like, the nine greatest experts on the Internet.”

— #SCOTUS Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan … #GonzalezvGoogle pic.twitter.com/loyONdfss8

— Howard Mortman (@HowardMortman) February 21, 2023

Given that this ultraconservative Court is not known for its restraint, their tentativeness here feels out of character. But a handful of exchanges yielded a hint about what makes this case different: money, and more specifically, the money of people who are already very rich.

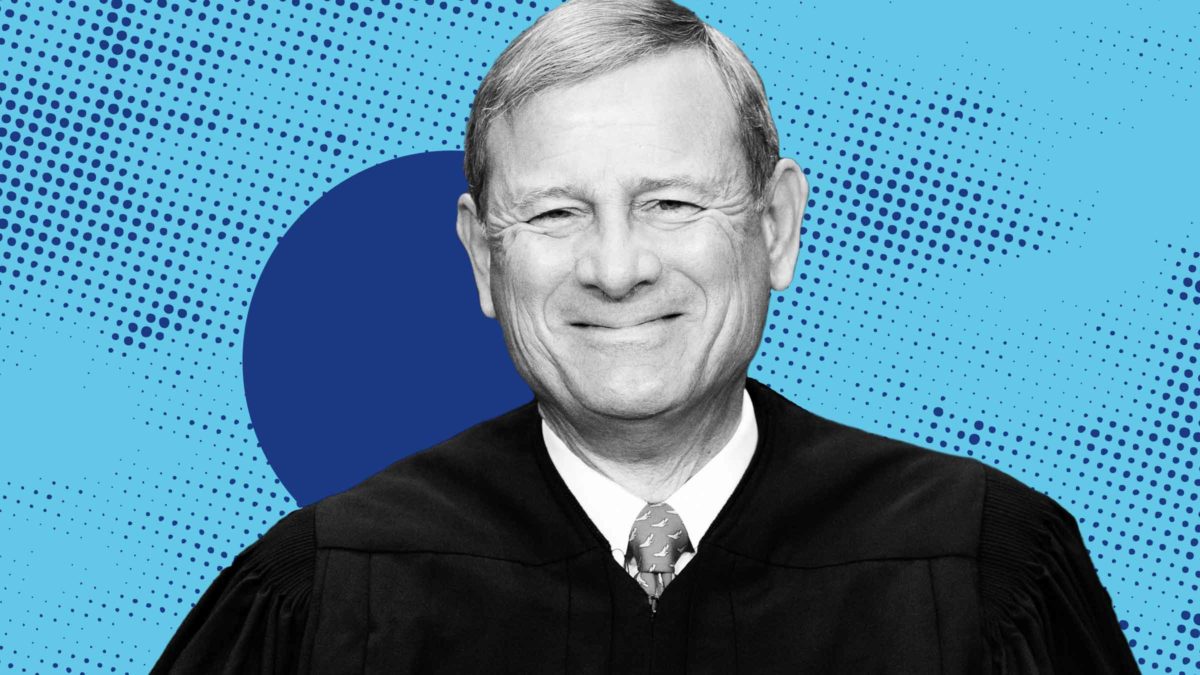

“Hundreds of millions—billions of responses to inquiries on the Internet are made every day,” said Chief Justice John Roberts. And without Section 230, he continued, “every one of those would be a possibility of a lawsuit.” Justice Brett Kavanaugh similarly expressed trepidation about “nonstop” litigation causing “a lot of economic dislocation” and grinding the Internet, which contributes some $2.5 trillion to the U.S. economy every year, to a halt. In other words, if the Court does something dumb here, there will be a hefty price tag associated with it.

The Supreme Court is many things, but above all else, it is aggressively, unflinchingly pro-business. Republican justices tend to be more sympathetic to corporate interests than their Democratic counterparts. But the six Republicans who sit on the Court right now are the six most pro-business justices in a century, according to a 2022 analysis from the University of Southern California’s Lee Epstein and the University of Virginia’s Mitu Gulati. During the Court’s 2020 term, when a business squared off against anything that is not a business, the business came out on top 83 percent of the time. If you’re looking for a rule of thumb for how the Roberts Court will decide a case, “What outcome is best for shareholders?” is a fine place to start.

As Epstein and Gulati discuss in detail, the Court’s unprecedented enthusiasm for business is not attributable only to its majority-Republican composition. (Today’s Democratic justices are even more business-friendly than many of their conservative predecessors; Kagan, for example, ranks just ahead of the late Justice Antonin Scalia.) Even so, there is no question which side corporate America favors here: In Gonzalez, Google was backed not only by First Amendment experts and Internet nonprofits, but also by Meta, Twitter, Microsoft, Yelp, ZipRecruiter, several industry groups, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, all of whom urged the justices to neither fuck around nor find out.

Chief Justice John Roberts (R) explains how big the Internet is to Justice Amy Coney Barrett (L) (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Many of the hot-button issues that come before the justices do not present such stark choices between capital protection and culture war wins. The effect of the Court’s war on campaign finance regulation, for example, is to relax restrictions on corporate political spending. Its “religious liberty” cases, from Hobby Lobby to Masterpiece Cakeshop to (soon) 303 Creative, enable business owners to flout costly obligations associated with following the law. Its anti-gun safety agenda props up a $70 billion industry; its anti-voting agenda helps more business-friendly Republicans win more elections in more places; its anti-union agenda spares well-heeled executives from the indignity of having to treat workers with respect. The Court’s anti-choice crusade is a little like a free space on the reactionary bingo card: No matter how many women are personally robbed of their bodily autonomy by Samuel Alito, shareholders will get their dividends checks on time and in the proper amounts.

In cases where the interests of the average Newsmax viewer align with those of Republican megadonors, the justices are fine with letting Josh Hawley and company celebrate symbolic victories over the woke mob. But as much as Clarence Thomas might want to see more engagement on his wife’s coup-curious Facebook posts, this isn’t a close call: If Republicans hate anything more than the excesses of cancel culture, it is forcing corporate behemoths to reduce their C-suite bonus budgets to cover the costs of anticipated litigation. The conservative urge to own the libs online—the conservative urge to do anything, really—will always yield to the prime directive: preserving corporate power.

During oral argument, some justices gestured to the idea that Congress, not a panel of nine unelected lawyers who wear pajamas to work, is best situated to update Section 230 for the 21st century. But if the conservatives indeed elect to stand down this time, thus dooming Ben Shapiro to a grim fate of monologuing about the injustices of shadowbanning, it won’t be because of their newfound commitment to the principle of judicial restraint. It will be because they never forgot which fights matter, and which don’t.