In 1973, a reporter for the St. Petersburg Times uncovered his own version of Watergate: An anonymous source handed him evidence that showed a utility company’s lawyer was secretly passing documents to two Florida Supreme Court justices to sway their vote on what was the most important case of the term. Florida’s new corporate income tax was about to go into effect, and this case would decide whether the utilities could pass the cost of the tax onto consumers through their monthly bills. The media scrutiny that followed uncovered at least two other instances of judicial misconduct, including justices using their influence to help their friends in the shadiest ways imaginable.

In one instance, a justice called another judge on the phone to ask for a more lenient sentence for a campaign supporter, and then wrote the opinion dismissing criminal charges against them. That justice resigned before he could be impeached, and eventually became a federal fugitive for conspiring to smuggle marijuana. Two other justices were impeached for their involvement with the utility company; one resigned, while the other narrowly avoided conviction by the Florida Senate.

This was supposed to be the low point for Florida’s Supreme Court: The state’s tradition of electing judges had rendered them no better than standard-issue corrupt politicians. At the same time, the reform-minded Democratic Governor, Reubin Askew, was establishing merit-based nominating commissions for each state appeals court. His original commission structure divided the nominations process between the Governor and the Florida Bar: three commissioners appointed by the governor, three by the Bar, and then the final three were selected by the prior six. Together, the nine would submit lists of potential nominees for the governor’s consideration.The people of Florida liked this idea so much that they later voted to incorporate the commissions into the state constitution.

(Photo by Mark Wallheiser/Getty Images)

Unfortunately, the Gulf Power case scandal and the reforms that followed did not fix the problems they were designed to solve. Today, Florida’s Supreme Court is once again a hyperpartisan entity stuffed with justices no different than the Republican governors who appointed them. In. In 2001, Governor Jeb Bush and the Republican-controlled legislature changed the nominations process again to consolidate power in the executive branch: Now, the governor directly appoints five commissioners, and chooses four more from a list submitted by the Florida Bar. The Bar’s involvement in this process is largely symbolic, however, as the governor can and does reject Bar lists as many times as they want.

When Bush was pushing for those changes, the Florida Supreme Court was relatively liberal. But in the decades since, the new nominations process has shifted the ideology of the Court far to the right. In 2018, the last three liberals reached mandatory retirement age and, after his narrow 2018 victory, Governor DeSantis appointed three more Federalist Society-affiliated justices. Those three, and another in 2022, came from lists given by a nominating commission where at least five out of nine members are affiliated with FedSoc. Much has been written about the quiet influence of the organization in the federal judiciary, but in Florida, they dominate in the open for all to see.

Although Florida voters have no power to hire justices, they do retain the power to fire justices. New justices face a “merit retention vote” in the first general election after the first year of their appointment. If not retained, the Governor must appoint a replacement from the commission’s recommendations as before. If they make it through that hoop, that justice has to face another retention vote in the general election just before their six-year term expires. Imagine if the country got to vote on whether to keep Amy Coney Barrett this November. That’s what happens every time Florida gets a new Supreme Court justice.

In 2022, three justices face their third retention election, and two more justices are up for their first retention vote. As conservative judges at all levels flex their muscles in courthouses across the country, Florida voters have the opportunity to evict a few of its own revanchist justices who think there are a few too many civil rights floating around.

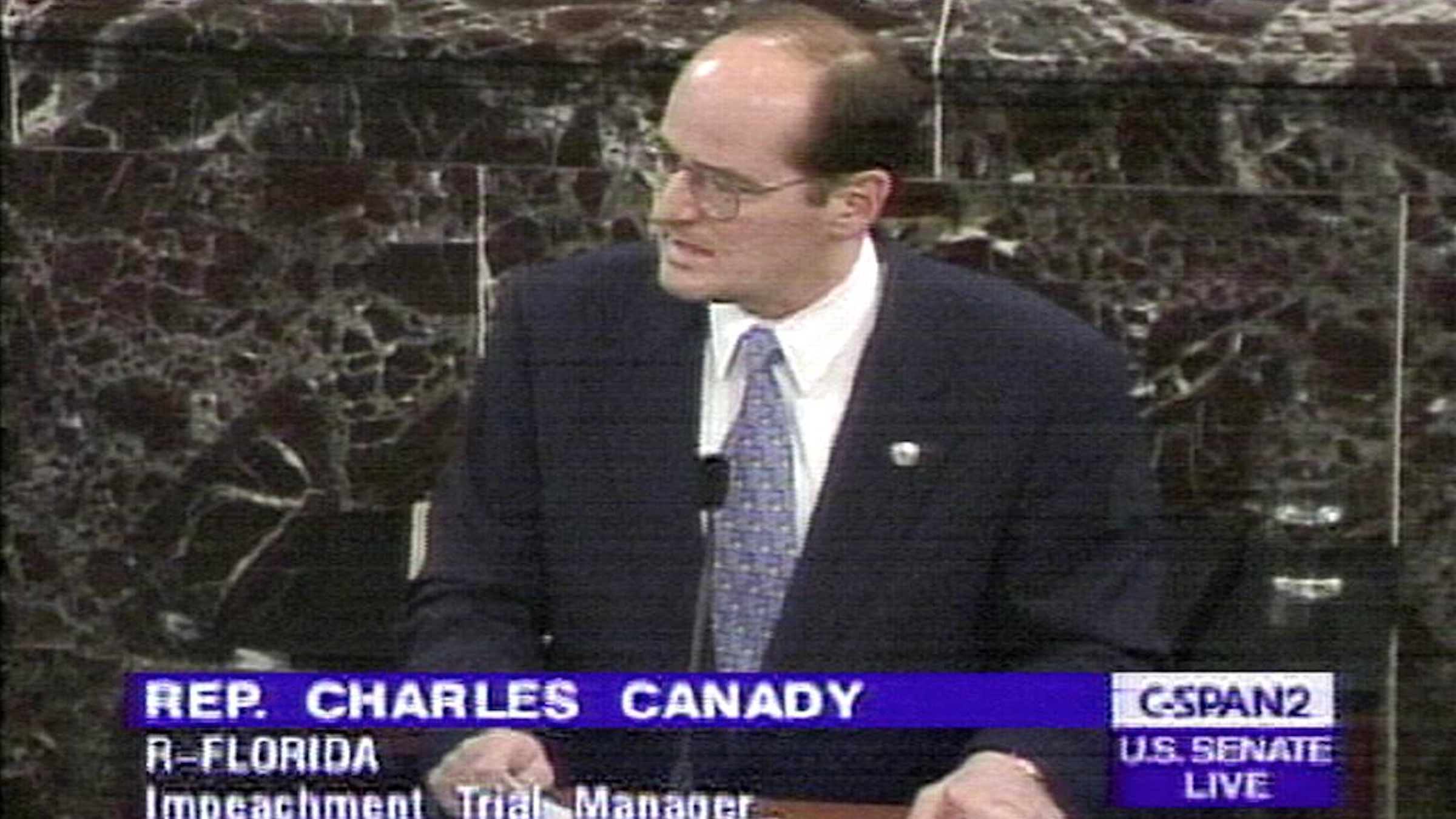

Among them is Charles Canady, who has been on the Court 14 years, appointed by erstwhile Republican Governor Charlie Crist. Previously, he was a Republican member of the Florida House of Representatives and then a Republican congressman, where he was an impeachment manager against President Bill Clinton. When liberals controlled the Court prior to 2018, he was known for fiery dissents. He dissented in, for example, redistricting cases that struck down no fewer than eight congressional districts because of racial gerrymandering, despite evidence that Republican state legislators conspired with Republican operatives to pack as many Black voters into as few districts as possible.

Canady’s pièce de résistance, though, was his 2016 dissent in a case about Florida’s death penalty procedure. The law in question allowed a judge to find all facts necessary to impose a death sentence, cutting out the traditional role of the jury. The U.S. Supreme Court found that it violated the Sixth Amendment right to a trial by jury, and ordered resentencing. When the case came back to the Florida Supreme Court, the majority ruled that the remand meant that all facts necessary to impose a death penalty must be found by a unanimous jury. In dissent, Canady claimed that the majority was reading too much into the remand, arguing that the right to a jury trial did not require that the jury unanimously recommend execution, too. After DeSantis replaced the last liberals, another death penalty appeal gave Canady the chance to overrule that 2016 case. In 2020, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed an order of execution in that case even though the trial court imposed that order over a split jury.

Just your classic apolitical jurist (Photo by C-SPAN / AFP) (Photo by C-SPAN/AFP via Getty Images)

Canady is frequently joined by his colleague Ricky Polston, who was also appointed by Crist. As an appeals court judge, he argued in favor of giving state money to religious charter schools, even though the state constitution strictly forbids giving any state money “directly or indirectly in aid of any sectarian institution.” On the Florida Supreme Court, he dissented from an opinion which, in its entirety, allowed the Family law section of the Florida Bar to file an amicus brief opposing a law which prohibited LGBTQ families from adopting children.

Justice Jamie Grosshans, appointed in 2020 by DeSantis, is the closest thing to an Amy Coney Barrett of Florida. As a law student in the mid-2000s, she was an event coordinator for something called the Institute in Basic Life Principles, which turned out to be an actual cult teaching about the ungodliness of blue jeans. She then interned at the Claremont Institute, the conservative think tank that gave us Trump’s personal coup lawyer, John Eastman, and served as a legal fellow at the Alliance Defending Freedom, a national organization that, per its web site, “exists to keep the doors open for the Gospel” and opposes abortion, same-sex marriage, and LGBTQ rights.

Justice John Couriel was the third DeSantis appointee to replace a liberal in 2018. His reliable vote for the majority’s conservative causes perhaps comes from his background in securities and corporate law, when he worked at a firm specializing in contesting “cross-border attempts to freeze assets.” In his first year on the Court, Couriel joined opinions that made it harder to sue for wrongful deaths caused by tobacco companies and easier to shield corporate executives from depositions.

Contrast Couriel with the fifth justice up for retention, Jorge Labarga, who has distanced himself from his colleagues. Appointed by Crist in 2009, Labarga is conservative, but not as brazenly political as his colleagues. He wrote the aforementioned first majority opinion on Florida’s death penalty procedure, and became the lone dissent when Canady’s vision for execution by judicial fiat won the day. He is by no means a progressive or even liberal justice, however; many of his “dissents” are in fact partial concurrences.

The stakes for these Supreme Court retention elections are as high as those for any election in Florida this fall. The marquee cases for their next term include reconsidering whether the state constitution’s right to privacy includes a right to abortion, and whether a constitutional amendment meant to protect a crime victim’s identity includes cops who kill while on duty. There is every reason to expect that the first four will rule the way that the Republicans who appointed them would. But if any of them were to lose their retention elections, the Court’s status as a rubber-stamp for the conservative agenda would suddenly be in jeopardy.

If DeSantis wins re-election—currently, he’s polling about six points ahead of his challenger, Crist, now a Democrat—he can replace any justice the voters reject with another loyal conservative. If Crist wins, however, he can overhaul the court immediately.

Historically, voters have not paid much attention to retention elections; to date, no appellate judge or justice has ever lost one. But scrutiny of the state’s highest court has increased after controversies involving other DeSantis appointees. If even one justice gets close to being replaced, it puts the entire system into question unlike any time since the last time justices were unmasked as partisan hacks in the 1970s.

Martin Dyckman, the St. Petersburg Times reporter who broke the Gulf Power scandal story, wrote a book about his experiences in 2008, just after Bush overhauled the Florida Supreme Court selection system. The last chapter featured an interview with Askew, the reformer Democratic governor, that contained a prophetic warning: Florida was condemned to repeat its history without an independent judiciary. In 2022, the state’s voters have the chance to show the black robes what accountability in a democratic society looks like.