Late last month, Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt went on Tucker Carlson Tonight to discuss the state of criminal law in Oklahoma following the landmark Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma. In the interview, Stitt claimed that as a result of the Court’s decision, individuals convicted of crimes could simply “show their Indian card” and get their convictions overturned; that tribal citizenship is determined on the basis of race because individuals “could be 1/500th, 1/1000th” degree of Indian blood and qualify for tribal citizenship; and that convicted offenders were submitting 23andMe-type DNA tests to successfully overturn violent convictions.

Clip via YouTube

While McGirt has changed the way many criminal matters are handled in Oklahoma, the claims of lawlessness by the right have been proven to be either embellished or outright false. What McGirt does have the potential to do, however, is take away the state’s taxing and regulatory power over nearly the entire eastern half of Oklahoma. Stitt is terrified of losing that power, so he and his administration are intentionally misleading the public about McGirt to diminish support for the Court’s decision and for the tribes generally, which are extremely popular in Oklahoma.

In 1997, Jimcy McGirt was convicted by the state of Oklahoma for raping and sexually assaulting a four-year old girl, and was sentenced to two consecutive 500-year sentences. Since his conviction, McGirt challenged Oklahoma’s jurisdiction over him because he is a citizen of Seminole Nation and his crimes took place within the original boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation. According to the federal Major Crimes Act, any Indian who commits a “major crime” within “Indian Country” is subject to “the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States.” The statute defines “Indian Country” as including “all land within the limits of any Indian reservation under the jurisdiction of the United States Government.” To oversimplify things a bit, McGirt argued that Oklahoma did not have jurisdiction to convict him because he was not really in Oklahoma at all.

The Supreme Court decided McGirt in July 2020. Written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, the opinion opens with what may go down as my favorite opening line of any case I’ve ever read: “On the far end of the trail of tears was a promise. Forced to leave their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama, the Creek Nation received assurances that . . . ‘[t]he Creek country west of the Mississippi shall be solemnly guarantied to the Creek Indians.’”

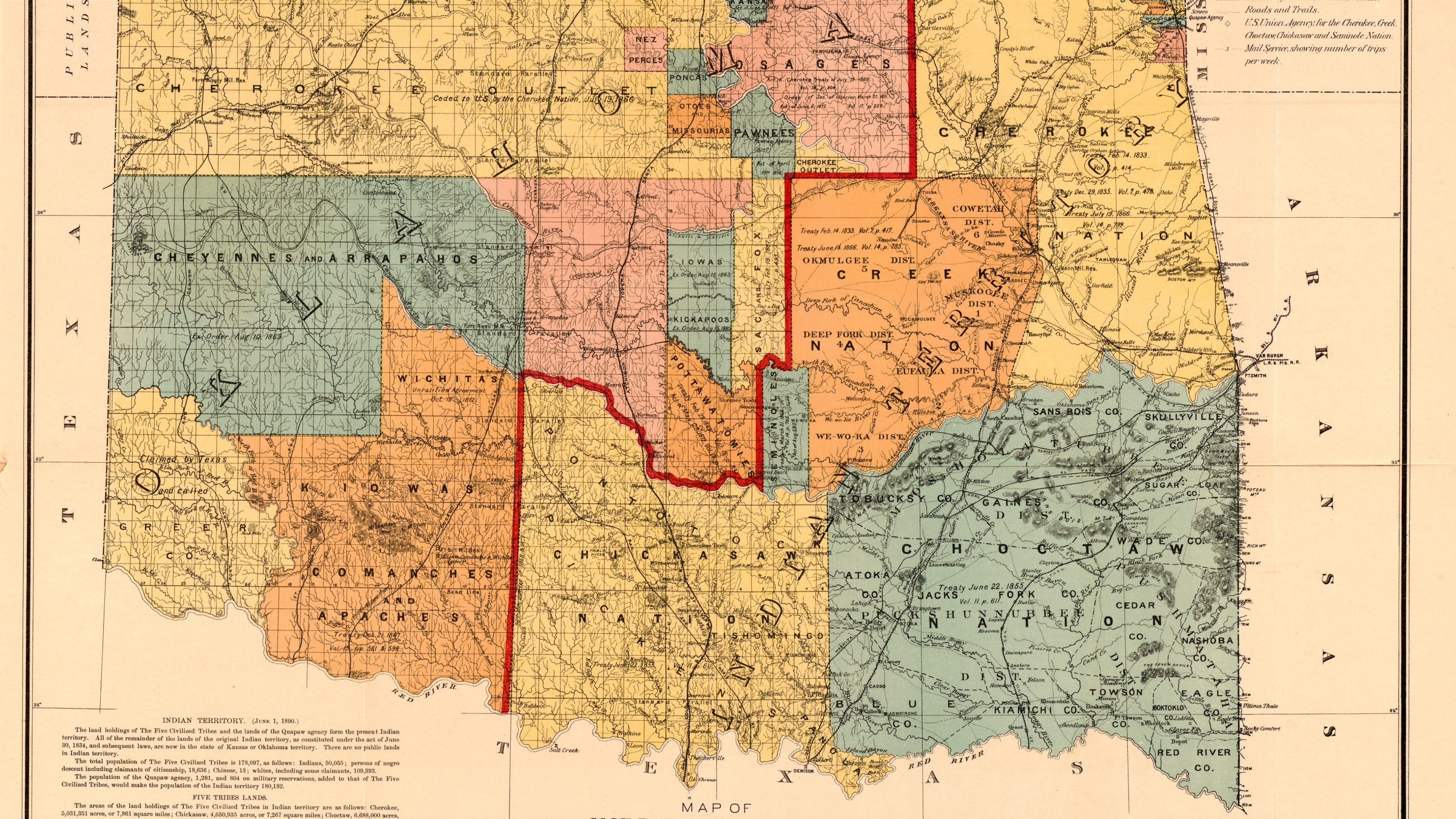

With a few strokes of his keyboard, Gorsuch said what was always true, but Oklahoma had ignored since statehood: that Congress alone can establish a tribal reservation, and Congress alone can destroy it. What this means in practice is that the entire area originally reserved for the Creek Nation is—and always has been—“Indian Country” for purposes of the Major Crimes Act. Because McGirt is a citizen of a tribal nation, and his crimes occurred in Indian Country, the Court overturned his conviction in state court.

Politicians and commentators on the right have willfully misstated the outcomes from Gorsuch’s opinion since it was issued. Attorney General John O’Connor and his predecessor Mike Hunter have filed dozens of challenges to the decision—most of which, in a remarkable coincidence, came after Justice Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed. Not to be outdone, in July 2021, Stitt—a citizen of Cherokee Nation himself—held a town hall-style meeting with law enforcement and district attorneys to discuss the effects of McGirt, but failed to invite tribal leadership. The administration also recently launched a web site where members of the public can anonymously share stories about how they’ve been impacted by the decision.

Yet its real-life effects have been minimal. A recent review of data released by the Oklahoma Department of Corrections revealed that 235 people successfully challenged their convictions under McGirt. Of those, only sixty-eight were released; the rest were charged in tribal or federal court. This includes Jimcy McGirt, who was convicted in federal court and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole in August 2021. Of those released, about half were serving time for nonviolent or drug charges. So, while the popular narrative is that McGirt has turned Oklahoma back into the Wild West, the reality is that your average Oklahoman is unlikely to even notice the change.

McGirt’s impact has been limited for several reasons. Most of those eligible for review under McGirt have already exhausted their federal appeals. And thanks to a recent (and dubious) state court decision, McGirt can no longer be applied to past convictions: In Bosse v. State, decided on March 11, 2021, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals—the state’s highest court on criminal matters—held that McGirt could not be applied retroactively, meaning that people whom the state already convicted cannot challenge the state’s jurisdiction. The U.S. Supreme Court recently declined to review the decision. What Bosse means in practice is that while McGirt has forced state and local law enforcement to work collaboratively with tribal and federal authorities moving forward, it does nothing for people who are already in state prison.

Shortly after Bosse, O’Connor announced that he would be directing district attorneys across eastern Oklahoma to rearrest the handful of people who were released under McGirt. It remains to be seen what he plans to do after that, as any retrial in state court will certainly face statute of limitations and double jeopardy challenges, in addition to objections under McGirt.

To the extent that McGirt puts anyone’s safety at risk, it’s the Indians who live and work in Indian Country in Oklahoma. The jurisdiction issue created by McGirt affects the state’s ability to prosecute not only Indians accused of crimes, but also non-Indian offenders who commit crimes against Indians. For example, I am a citizen of Cherokee Nation, and I live and work within the Chickasaw Nation Reservation. If I am the victim of a crime while at home or at work that falls under the Major Crimes Act, the perpetrator can only be prosecuted in federal or tribal court. There is a risk that these types of crimes could go under- (or un-) punished, particularly when the victims are indigenous women and girls whom the legal system already fails spectacularly to protect.

The real reason Stitt is so mad has very little to do with public safety, and a whole lot to do with the state’s power over the tribes and their citizens. The logic of McGirt has the potential to erode the state’s civil and regulatory authority over tribal reservations that meet the Major Crimes Act definition of “Indian Country.” Gorsuch’s opinion only addressed whether the Creek Reservation is Indian Country, but since then, state courts have applied its holding to several other tribes in Oklahoma. These newly reaffirmed tribal reservations cover much of the eastern half of Oklahoma. And because many federal statutes use the MCA’s definition of Indian Country, McGirt could overhaul Oklahoma’s political landscape in a hurry.

This possibility might sound overblown, but cracks in Oklahoma’s authority are already starting to form. A federal judge recently upheld a decision by the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement that stripped the state of regulatory authority over surface mining in tribal reservations. Oklahoma is known for its pro-industry regulatory scheme. If the federal government—or worse yet for the industry, the tribes—were to assume jurisdiction, significant economic damage could follow in a state with an economy based almost entirely on resource extraction. The state’s power to tax tribal citizens is also at risk. Currently, Stitt and the Oklahoma Tax Commission are the subject of a lawsuit claiming that Oklahoma lacks the authority to tax Indians who live and work on one of six tribal reservations. If the suit is successful, the state could lose nearly $200 million in annual tax revenue.

The unique circumstances Stitt faces in the wake of McGirt would be challenging for any governor of any state. But whatever his reason for misleading the public about the impacts of McGirt, he is using an age-old conservative tactic to strike fear into the hearts of his political base. Using this kind of rhetoric is certainly not new, but it will have lasting impacts on Oklahoma’s relationship with the tribes moving forward. If the governor really wants to address the potential problems caused by McGirt, he should come to the table and work with the tribes to address them. So far, he has shown no willingness to do that.

Due to an editing error, an unfinalized draft of this piece was originally published. It has since been corrected.