Last Wednesday, the Supreme Court’s six-justice conservative supermajority uncharacteristically handed Black Louisiana voters a major victory in the state’s ongoing redistricting saga. In 2023, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a district court’s finding that the state’s congressional map illegally discriminated against Black voters, and ordered the legislature to draw a new map with a second majority-Black district. Once the state legislature did so, a different court in a second lawsuit—this one brought by self-identified “non-African American voters”—blocked the new map from taking effect.

Yet the Supreme Court stepped in to temporarily pause that second decision, in part because Louisiana’s Attorney General, a Republican, insisted that the state absolutely needed to have a legal map by Wednesday to administer the 2024 election without “chaos.” Incredibly, thanks to one of the most anti-voting Supreme Courts in the institution’s history, Louisiana will have two majority-Black congressional districts in the 2024 election, effectively putting Democrats one seat closer to taking back the House.

All told, not a bad short-term outcome, but there’s a big asterisk: Purcell v. Gonzalez, the only case cited in the Court’s one-paragraph order. The Court used Purcell, a case it decided in 2006, as shorthand to say that courts must stop meddling in elections as Election Day approaches, implying that giving Louisiana a decision any later than May 15 would have been too disruptive or confusing to voters. This application of Purcell expands the most flexible anti-voter tool in the conservative justices’ arsenal, giving them more power over more elections not just this year, but for the indefinite future. This reality was not lost on the liberal justices, all of whom registered their disagreement with the outcome. “Purcell has no role to play here,” wrote Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. “There is little risk of voter confusion from a new map being imposed this far out from the November election.”

In Purcell, the Ninth Circuit had temporarily blocked an Arizona voter ID law because its requirements violated federal law, including the Voting Rights Act. But less than three weeks before Election Day 2006, the Court issued a short, unanimous, unsigned opinion reversing the Ninth Circuit, which it criticized for failing to recognize that “[c]ourt orders affecting elections…can themselves result in voter confusion,” a risk that ostensibly increases closer to Election Day. So, citing the need for “clear guidance,” the Court reinstated Arizona’s voter laws, effectively ordering the state to adopt entirely new (and not obviously legal) procedures on three weeks’ notice.

The idea behind Purcell is that courts should account for the risk of disruption and voter confusion before making changes to election procedures. But in recent years, conservative courts have turned the “Purcell principle” into an expansive tool for undoing voting rights wins that would be, in their estimation, implemented too close to Election Day. The Supreme Court has led the charge, issuing a series of 2020 orders reversing lower-court victories in lawsuits concerning pandemic-related changes to voting procedures. In the highest-profile of these, the Court relied on Purcell to undo a lower-court ruling that required Wisconsin to count mail ballots that had been postmarked after the state’s primary election day, which functionally forced Wisconsin voters to take their chances with in-person voting during a pandemic.

Voters wait to cast ballots in the Wisconsin Democratic primary election, April 7, 2020 (Photo by KAMIL KRZACZYNSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

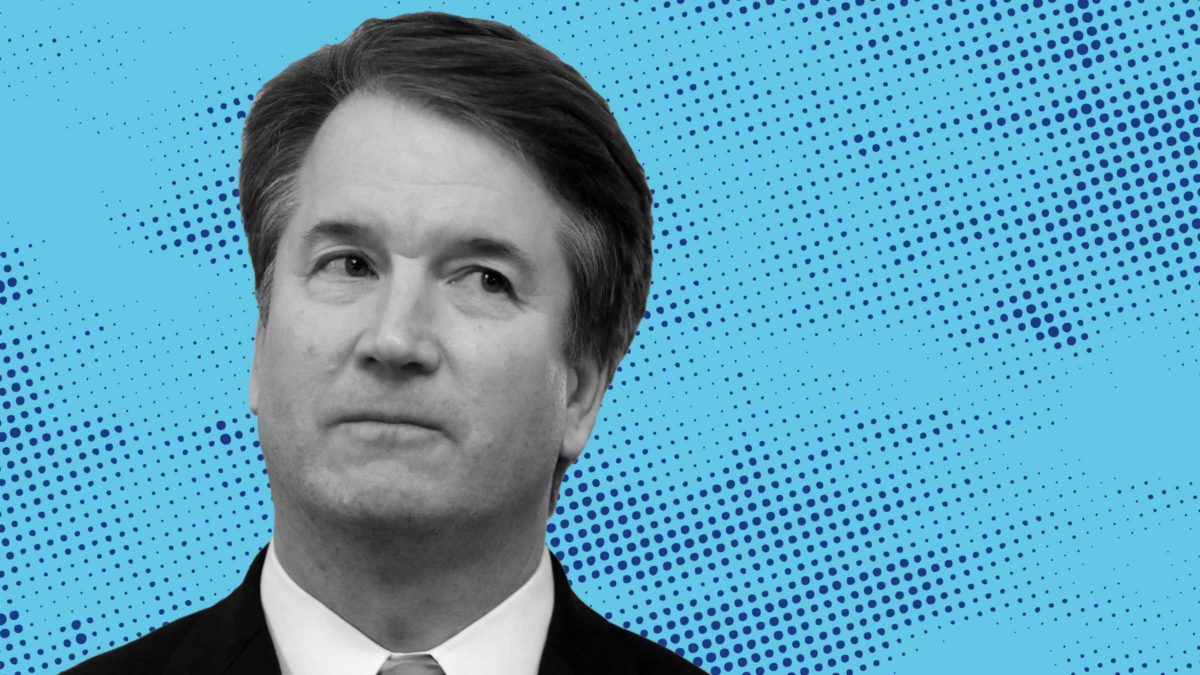

The low point in the Court’s application of Purcell (so far) came in 2022, after a lower court struck down Alabama’s congressional map for having too few majority-Black districts. Sure enough, the Supreme Court stepped in to keep the discriminatory map in place, and in a concurrence, Justice Brett Kavanaugh explained the lower court decision violated the Purcell principle because “federal district courts ordinarily should not enjoin state election laws in the period close to an election.” That’s a lot broader and more automatic than anything in Purcell itself, and its application to a decision that came down in January extended the “too close to an election” no-go zone to a robust nine months. The decision required Alabama to conduct the 2022 elections under a map that the Supreme Court itself later found to be illegal, and in the meantime handed Republicans an extra congressional seat by blocking the second majority-Black district.

The Alabama episode drives home how Purcell prioritizes hypothetical procedural concerns over concrete violations of people’s rights, leading to absurd situations where unfair voting laws remain in force because a judge declares it chronologically improper to strike them down. Purcell also functions as a one-way ratchet that only works against voting rights plaintiffs: There is no analogous rule that, for example, requires appellate courts to second-guess election decisions every time the state wins one.

What’s especially troubling about the Louisiana case is that the Court is invoking Purcell at the request of the state, which argued that the case “screams for a Purcell stay” because chaos would purportedly ensue if Louisiana did not have a legal map by May 15. By granting the state’s wish, the Court is strongly suggesting that Purcell kicks in whenever the state says it does, which functionally allows red states to pause election lawsuits on a date of their choosing. And even though Louisiana’s remedial map will govern the 2024 election, the Supreme Court is using Purcell to wrest control of the case from the district court, setting itself up to micromanage redistricting in Louisiana (and elsewhere) from here on out. There are a lot of things a Court controlled by a six-justice conservative supermajority can do with that power. None of them are good.

Expanding Purcell is bad news because Purcell is inherently regressive. It isn’t a principle so much as a power grab, a blank check courts can wield however they want against voting rights protections they don’t like. It isn’t anchored in any part of the Constitution or other authorizing law, and judges implement it without relying on evidence or testimony, let alone concrete experience in election administration. And every part of Purcell is ludicrously open-ended. How close to the election is too close? One month? Two? Nine? (As Jackson argued, in Louisiana, there’s still ample time for a district court to get a map in order because the court can easily modify any pre-election deadlines a later ruling might disrupt.) In December 2023, the Fifth Circuit used Purcell to rule (and the conservative justices affirmed) that Galveston, Texas, had to stick with an illegal districting map for all of 2024 because a district court ruled too close to the filing deadline for primary election candidates, which fell a full 11 months before Election Day. The only check on how far Purcell will go is how brazenly judges are willing to wield it.

When there are fewer than 12 months until Election Day and you can stop a voting rights law from taking effect (Photo by Andrew Harnik-Pool/Getty Images)

Purcell’s deliberate open-endedness provides cover for decisions that are arbitrary at best and mendacious at worst. A Republican judge faced with a credible voting rights lawsuit can’t really say “I am keeping this registration requirement in place because doing so will help Republican candidates.” (They could do it, I guess, but they’d be overturned on appeal and face at least some reputational consequences.) But that same judge can say “I am keeping this registration requirement in place because I think it’s too close to the election to change it” without anyone batting an eye. This result has the same effect on voters, and maybe the same underlying motive, but Purcell—and Purcell alone—allows courts to reach their desired result.

Louisiana is the latest example, but will not be the last. 2024 election litigation is already underway, and it’s all taking place in the shadow of Purcell. As plaintiffs rush to obtain decisions in time to avoid the Purcell time bomb, the states facing these lawsuits have every incentive to drag their feet, hoping that they, too, can pull a Louisiana and get a court to let them set their own deadlines. The fact that it’s so hard to know when Purcell will kick in, where it will or won’t be applied, and how the Supreme Court might intervene creates exactly the electoral chaos and uncertainty Purcell is supposed to prevent. But because this chaos gives the conservative justices license to keep doing whatever they want with elections, they don’t seem to mind one bit.