The Supreme Court ended its term in July doing one of the things it does best: making it harder for Americans, particularly the poor and people of color, to vote.

This time, the justices upheld two Arizona rules: one that requires election officials to disqualify ballots cast at the wrong precinct, and another that makes it a crime to collect ballots from eligible voters and deliver them to polling places. As the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals had found, the rules at issue in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee disproportionately disenfranchise the state’s Hispanic and Native voters—which is, of course, the reason Republicans like the rules so much. The Court, however, insisted that they did not violate the Voting Rights Act.

The Court’s decision was wrong. As the three liberal justices pointed out in dissent, Arizona’s rules both clearly violate the plain language of the Act and also run afoul of its purpose of protecting the voting rights of nonwhite Americans. To conclude otherwise, the conservative majority operated in what Justice Elena Kagan rightly blasted as “a law-free zone.”

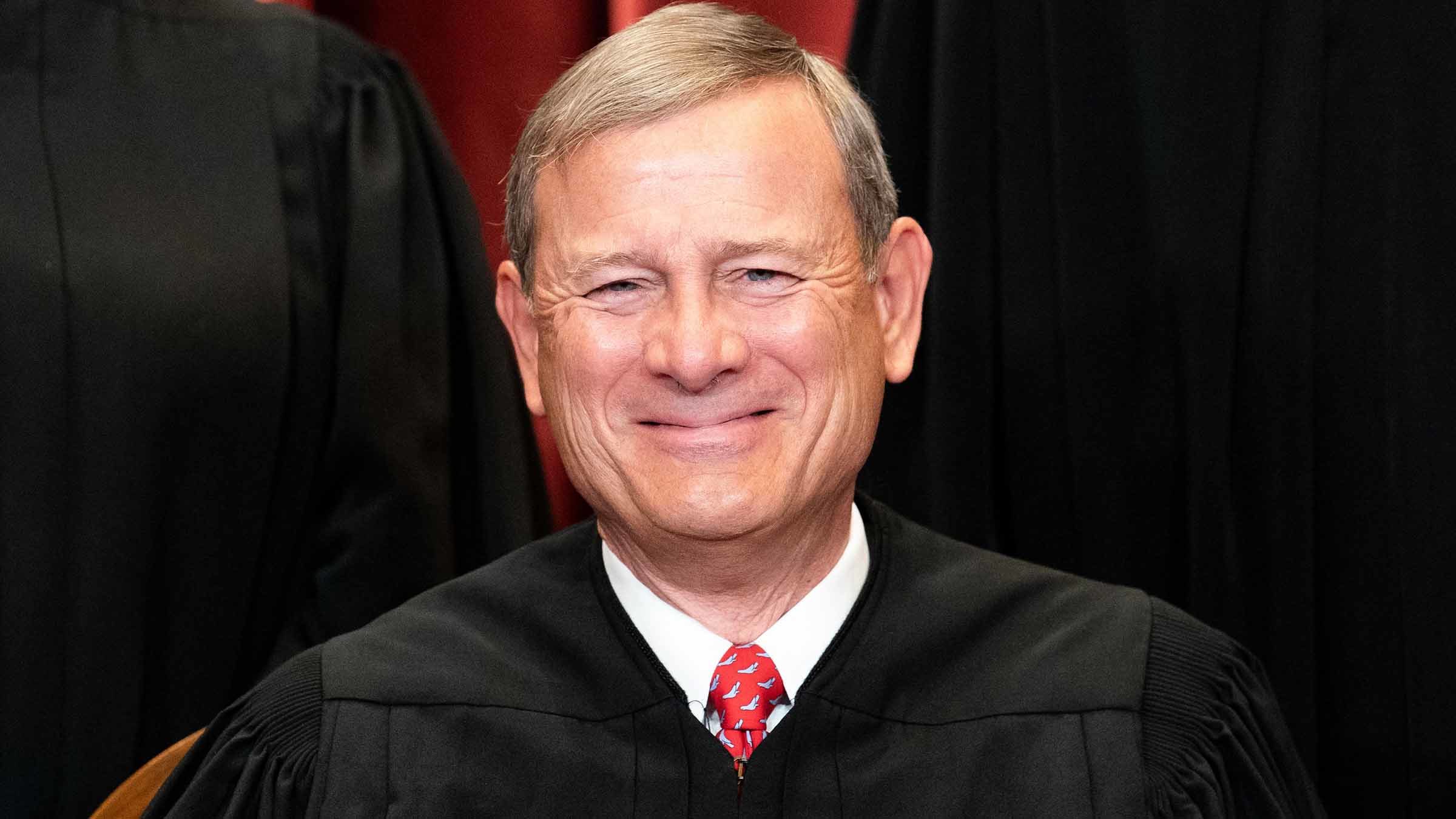

But for the Court under the leadership of Chief Justice John Roberts, rulings of this kind are a feature, not a bug. Brnovich is only the latest instance in which a Court controlled by Republican appointees contorted itself to rule in a way that helps Republicans win elections.

In recent weeks, the Court has embarked on a charm offensive to persuade the American public that it is not a political body. Justice Stephen Breyer has used his book tour to reassure skeptical would-be readers that the justices are not political actors. Justice Amy Coney Barrett recently insisted, after being introduced by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell at a University of Louisville center named after Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, that the Court does not act “in a partisan manner” and that its justices are not “partisan hacks.” Justice Clarence Thomas also chimed in, asserting despite having personally generated decades of evidence to the contrary that justices do not rule based on their “personal preferences.”

There can be little doubt, to anyone paying attention, that the Roberts Court is “political.” That is true of its rulings on a wide array of issues, from abortion access to workers’ rights. In no area, however, is its bias more obvious than in its election law cases. The single question that best explains the results in these cases is not, for example, “What would the Founders have done?” or “What does the law’s text tell us?” It is, invariably, “What would the Republican Party want us to do?”

The Court has never been a strong proponent of universal suffrage, and its history of shameful voting rights decisions long predates the Roberts Court. Before the Civil War, in cases like Dred Scott v. Sandford, it ruled that Black Americans had virtually no rights at all, and certainly not the right to vote. After the Civil War, when the Fifteenth Amendment purported to extend the franchise to Black men, the Court refused to make that promise a reality. In 1903, when Black citizens of Alabama challenged the state’s blatantly discriminatory voter registration regime, the Court threw out the suit in Giles v. Harris. The Court could have transformed American democracy by issuing a robust defense of the voting rights of Black citizens. Instead, it firmly sided with white supremacy.

There was a brief period, during the Warren Era of the 1950s and 1960s, when the Court actually believed in voting rights. In Baker v. Carr, it applied the doctrine of “one person, one vote” to dismantle the nation’s wildly unequal legislative districts; in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, it struck down the use of poll taxes that many Southern states had used to disenfranchise Black residents in their state elections. These rulings were so influential that Chief Justice Earl Warren said, at the end of his career, that he considered Baker to be the most important decision of his nearly two decades on the Court.

The Court veered sharply away from its support for voting rights in the early 1970s, after Warren retired and Richard Nixon’s appointees gave rise to the modern conservative Court. Its turn against voting rights culminated in 2000, when the Court in Bush v. Gore famously took the audacious step of deciding a presidential election. As the state’s 25 critical Electoral College votes hung in the balance, the Court’s 5-4 ruling, which fell precisely on ideological lines, ordered Florida to stop counting valid votes. It did so on made-up legal grounds: the Court was so unserious about its interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause that it declared that its analysis was “limited to the present circumstances” and could not be applied in future cases. The decision of the five conservative justices functionally handed the White House to the Republican candidate, George W. Bush.

Conservative justices may want people to believe the Court is not acting politically, but how else would they explain its election law jurisprudence?

Since Bush v. Gore, the Court’s voting rights cases, with striking regularity, have perpetuated the same dynamic. In 2008, in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board, the Court ruled that states could adopt laws that require voters to produce kinds of ID that many poor people do not have. It was a major win for the Republican Party, since voters most likely to lack the requisite IDs—poor people, city residents without driver licenses, people of color—skew heavily Democratic. The Court, however, made the absurd assertion that there was no evidence the law imposed “excessively burdensome requirements” on any class of voters.

The result in Crawford not only upheld Indiana’s harsh voter ID law, but also gave the green light to other state legislatures to follow suit. Many did. Richard Posner, an appeals court judge appointed by Ronald Reagan whose decision the Court affirmed in Crawford, later admitted that he and the Court had been wrong; laws like Indiana’s, he said, are “now widely regarded as a means of voter suppression.” That is certainly how many Republicans regard them. In 2012, Pennsylvania’s state House Republican leader created a stir when he said the quiet part out loud, declaring that Pennsylvania’s strict new voter ID law would “allow” Mitt Romney to carry the state against President Barack Obama.

Similar rulings followed. The Court cut out the heart of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 in Shelby County v. Holder, invalidating a key provision that required state and local election officials to get federal approval before making changes in election procedures that made it harder for minorities to vote. The constitutional reasoning was even shoddier than in Crawford, and as in Bush v. Gore, the Court divided precisely on ideological lines. Once again, the ruling was a huge boon for Republicans, since it cleared the way for election officials to adopt an array of obstacles to prevent Democratic-leaning voters from casting ballots, including closing thousands of polling places, many in areas with significant nonwhite populations.

In 2018, in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, the Court gave states wide leeway to remove qualified voters from the voting rolls—another tried-and-true Republican voter suppression strategy—even though a federal law ostensibly prohibits the sort of aggressive purges at issue in the case. Justice Sonia Sotomayor rightly upbraided the majority for upholding “a program that appears to further the very disenfranchisement of minority and low-income voters that Congress set out to eradicate.”

A year later, the Court again delivered for the Republican Party in Rucho v. Common Cause, when it ruled there is no constitutional bar against partisan gerrymandering—a practice abused by both parties, but that benefits Republicans far more than Democrats. For years, the Court had dithered on this issue, alluding to the need for a constitutional principle that could be applied in partisan gerrymandering cases. In Rucho, it declared itself unable to stop lawmakers from subordinating representative democracy to their own job security.

What are the odds? That in case after case, the Court keeps ruling in the way that maximizes Republican votes, almost always exactly on ideological lines? Justices Barrett and Breyer and Thomas may want people to believe the Court is not acting politically, but how else would they explain its election law jurisprudence? Sometimes it defers to state election officials, as in the voter ID and voting roll purge cases; sometimes it does not, as in Bush v. Gore. Sometimes it makes up fictional constitutional principles, as in Shelby County; sometimes it insists it just can’t think of a workable constitutional principle, as in Rucho. Partisanship is the only throughline.

The Court’s bending of the law in favor of Republicans matters. As Justice Elena Kagan noted in her dissent in the Arizona case, “elections are often fought and won at the margins,” and in 2020, Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in Arizona by just 10,457 votes. The Court placing its fist on the scale can do considerable damage to democracy. Unfortunately for those of us who hope to live in one, this result is exactly what the Roberts Court wants.