On Tuesday, at the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention, over 10,000 church representatives voted to pass an “omnibus” resolution that includes a call for the Supreme Court to overturn Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 decision that legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. The resolution characterizes “rulings like Obergefell” as “legal fictions” that “undermine the truth of God’s design” and “lead to social confusion and injustice,” and declared that lawmakers have a “duty” to “affirm marriage between one man and one woman.”

The Southern Baptist Convention, the nation’s largest Protestant denomination, has long opposed marriage equality, and filed two amicus briefs in Obergefell saying as much. But this is the first time it has formally taken the position that the Court should end the right. This new aggressive stance was caused not by a change in the SBC’s views, but by a change in the Supreme Court’s composition: Ten years later, only two of the justices in the Obergefell majority remain on the bench. And in that court’s place is a conservative supermajority that has proved itself eager to strike down landmark precedents that protect people’s rights. Today’s Supreme Court inspires reactionaries to pair their animus with action.

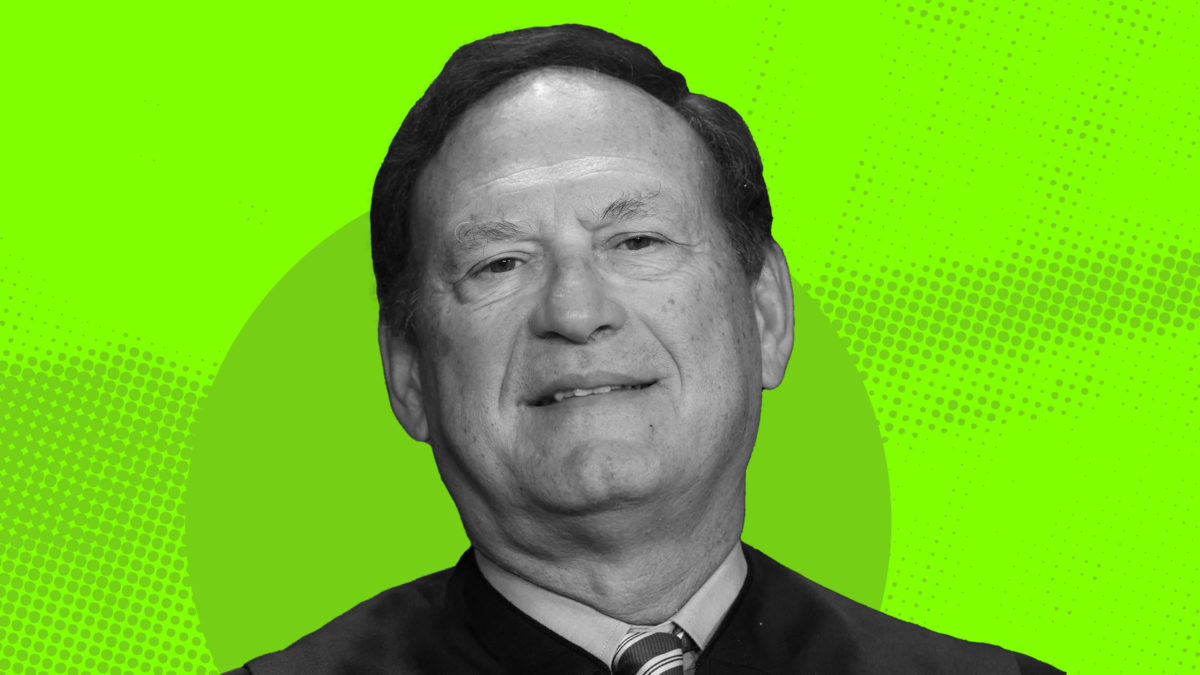

Three years ago, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 49-year-old precedent that recognized the constitutional right to abortion. According to Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the Court’s opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, any right not specifically enumerated in the Constitution is not protected by the Constitution unless it is “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition.” In other words, if you’re part of a group that had to fight for its rights at any point after 1868, when Congress ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, your rights probably aren’t real.

Obergefell explicitly rejected this approach, declining to permit “the past alone to rule the present.” Writing for a five-justice majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy acknowledged that the Constitution’s drafters “did not presume to know the extent of freedom” and instead “entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.” Obergefell strengthened the legal foundation for conferring constitutional protections to groups to whom such protections were historically denied. So Alito weakened it, aiming to keep marginalized people from building (or rebuilding) their rights.

Alito would claim he did no such thing: In Dobbs, he repeatedly assured the reader that abortion is “unique.” Unlike abortion, Alito says, the cases protecting the right to marry a person of a different race or the same sex, the right to obtain contraceptives, the right not to be sterilized without consent, and so on did not involve “the destruction” of “potential life.”

Based on this special embryo exception, Alito concludes that Dobbs does not “cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” Justice Brett Kavanaugh repeated this for emphasis in a separate concurrence. “Overruling Roe does not mean the overruling of those precedents, and does not threaten or cast doubt on those precedents,” he said.

No one really bought it. Friends and foes alike reasoned that if the Court could say the Constitution doesn’t protect abortion because it is insufficiently historical, it could just as easily say the Constitution doesn’t protect same-sex or interracial marriage, birth control, and countless other rights that the Framers didn’t specifically identify some 200 years ago. They only disagreed about whether that was a good thing. Anticipating their opening, some conservative activists submitted amicus briefs in Dobbs urging the Court to go ahead and overturn its precedents protecting abortion, marriage equality, and the decriminalization of same-sex intimacy in one fell swoop. The Court didn’t take that step, but it was clear what path they were on: The same day the Court announced its decision, the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary excitedly remarked that the Court’s opinion wasn’t only a reversal of Roe. “What you have here really is a reversal of a revolution,” said Albert Mohler, Jr.

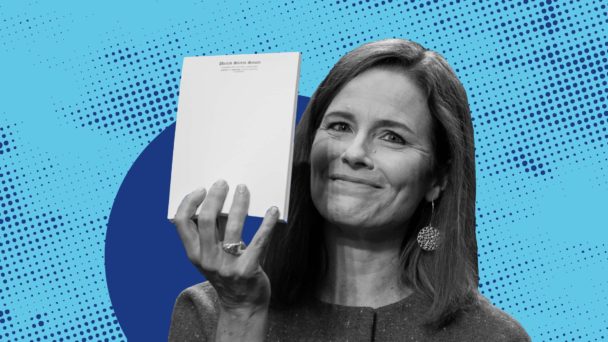

Most American adults are not on SBC’s side—support for same-sex marriage has hovered between 68 to 71 percent since 2021. But the conservative movement doesn’t need most Americans. It only needs most of the Court. With three Obergefell dissenters still on the bench plus three Donald Trump appointees, conservatives even have one justice to spare.

Dobbs encourages conservative movement actors to be more ambitious, and make more use of their judicial allies. The conservative justices renewed the movement’s political will to take down Obergefell and showed them what argument they should use to do it.