In 2022, the Republican state legislators in charge of redrawing South Carolina’s electoral maps exiled tens of thousands of Black voters from Congressional District 1, a district that had long been anchored by the city of Charleston. Republicans dominated District 1 for decades, but as Charleston’s Black population grew, the district began to shift from red to purple. In 2018, Joe Cunningham became the first Democrat elected to represent in 40 years, winning 50.6 percent of the vote. Republican Nancy Mace ousted him in 2020, again by winning 50.6 percent of the vote.

The 2022 racial gerrymander was a gambit to keep the suddenly-up-for-grabs congressional seat in Republican hands. It was also illegal: Last year, a three-judge federal district court panel struck the map down as intentionally racially discriminatory and ordered the state legislature to make a new redistricting plan.

But instead of doing that, the Republican lawmakers sought a reprieve from the Republicans on the Supreme Court—and, in a roundabout way, they just got one. On Thursday, the same federal court ruled that because of the Supreme Court’s inaction on this case, South Carolina may legally use the map that a federal court has recognized as unlawful and racist for its 2024 primary and general elections.

Throughout its history—and especially in the last few years—the Court has rightfully garnered considerable attention for making dramatic changes to substantive law, like curbing access to abortion care and expanding access to guns. But the justices in the conservative supermajority have many legal levers at their disposal that allow them to achieve their regressive policy goals without the hoopla associated with writing a major opinion. This gerrymandering case is only the most recent example of the Court slow-walking important cases in a way that lets the GOP run out the clock on democracy. Procedure can be just as important as substance in making American life more unjust and unfair.

After the trial court ruled South Carolina’s District 1 illegal, the state’s Republican lawmakers appealed to the Supreme Court. And when the Court agreed to take up the case in Alexander v. NAACP, the lower court put its own ruling on hold, explaining that it would not consider a remedial plan during the appeal and instructing the legislature to submit its plan within 30 days of the Supreme Court’s final decision. But although the justices heard oral argument nearly six months ago, on October 11, 2023, they have done nothing about it since.

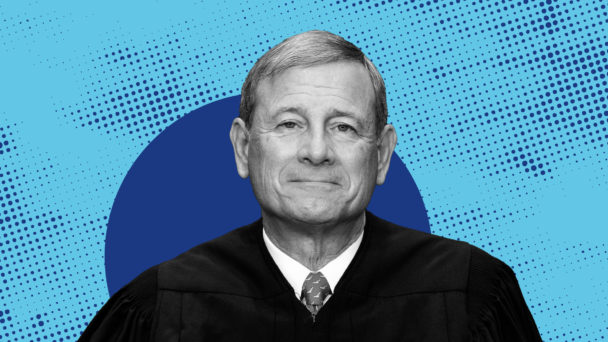

Nancy Mace, who will have an easier time holding on to her job in 2024 (Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Time continued its inexorable march forward while the justices were sitting on their hands. Finally, on March 28, the lower court decided that the primaries are too soon to expect an alternative map to be submitted and approved, even if the justices were to decide the case tomorrow. Candidate filing for the South Carolina elections is already open; the primary is scheduled for June 11, and military and overseas voters must cast their ballots by April 27.

Judge Mary Geiger Lewis, an Obama appointee, recognized that it is “unusual” for a federal court to allow an election to occur under a map that it previously deemed an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. Yet, she concluded in an opinion that made the panel’s frustration clear, “with the primary election procedures rapidly approaching, the appeal before the Supreme Court still pending, and no remedial plan in place, the ideal must bend to the practical.” The court modified its ruling to block the unconstitutional map…after the 2024 election cycle. The takeaway for Black voters is that their rights depend not on the commands of the Constitution, but the capriciousness of the Court’s conservatives.

This isn’t the first time the Court has left Americans waiting and worse off. In Allen v. Milligan, decided in 2023, the Court affirmed that Alabama’s congressional map was an illegal racial gerrymander—but only after it issued an unsigned order in February 2022 that allowed the map to be used in that year’s midterm elections. Again, there is no reason for the Court to bide its time like that other than to empower Republican lawmakers by excluding Black people from the political process. Republicans went on to win a razor-thin majority in the House of Representatives, at least in part thanks to the Court’s strategic inaction.

The most transparent and disturbing example of the Court’s deliberately glacial pace may be its embrace of former president Donald Trump’s legal strategy of “delay, delay, delay.” Trump has been trying to stall various legal proceedings in a bid to avoid prosecution for his litany of crimes, including by making the claim that presidents enjoy categorical immunity from criminal prosecution. Not only did the Court agree to hear his claim, it scheduled oral argument for the very last day of its term. Even if the Court eventually decides that, no, presidents can’t have a free pass for crime, there may not be enough time before the 2024 election for Trump to be prosecuted. This is by design: Shielding Trump from legal liability increases the possibility of a second Trump presidency, with even more opportunities for Republican activists to take the bench and reshape the country by judicial fiat.

There’s an old saying, often attributed to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that justice delayed is justice denied. The Supreme Court’s conservatives know it to be true. What the Court does—and whether and when it chooses to do anything at all—can significantly impact the legal and political landscape. And its actions and inaction alike are in service of the Republican Party.