After the most recent census, South Carolina Republicans worked so hard to reduce Black electoral power while redrawing the state’s congressional maps that a lower court described them as “effectively bleaching” a key congressional district. Today, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP to determine if this electoral Clorox poses any constitutional problem. After two hours of questioning, the Court’s Republican justices seem inclined to conclude it does not.

In theory, the practice of redrawing maps every ten years ensures equal representation for equal numbers of people. In practice, lawmakers abuse the process to preserve their jobs. Put a couple thousand people here or move a district line there, and you can almost guarantee a decade’ worth of electoral victories before anyone even has a chance to cast a vote.

The map at issue in Alexander is an egregious example of this practice. South Carolina’s Republican-controlled legislature moved over thirty thousand Black residents out of the state’s first congressional district—over sixty percent of the district’s Black population—thus ensuring that the remaining Black voters couldn’t threaten the Republican Party’s dominance. After the state’s chapter of the NAACP sued, a three-judge federal district court panel determined that the map “made a mockery of the traditional districting principle of constituent consistency” and unanimously ruled that it was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

In a world where the Supreme Court cared about silly stuff like “legal standards” or “Black people,” that would probably be the end of the story. Traditional legal principles allow appeals courts to intervene if a lower court didn’t follow the rules, but not if the losing party simply didn’t like the result. To that end, appeals courts generally defer to trial courts’ findings of fact unless the judge below made a clear error. This is a high bar: It means that the lower court’s finding wasn’t even plausible—not just that a different judge might have weighed the evidence differently.

Here, the trial court found that race was the predominant factor that Republicans considered when drawing the map. And since racial gerrymandering is (for now) illegal, they lost. But at the Court, South Carolina Republicans are urging the justices to buy a different argument: Lawmakers drew this map not to discriminate against Black people, but to discriminate against Democrats. And since the Court held in 2019’s Rucho v. Common Cause that federal courts can’t resolve partisan gerrymandering claims, the judges below got it wrong.

On Wednesday, the liberal justices peppered the legislature’s attorney with questions that emphasized that the legal standard is not on his side. When he argued that the lower court didn’t weigh the evidence as he thought it should have, Justice Kagan was audibly irritated. “That’s the legal error, is that they didn’t correctly weigh the evidence?” she asked. Justice Sotomayor similarly observed that the lawmakers were “in a very poor starting point,” and described herself as “really troubled” by the absence of any apparent clear error.

After Justice Samuel Alito asked a series of pointed questions about whether the district court evaluated the evidence properly, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pushed back in the form of a polite question. “I didn’t know that we were to evaluate whether we agreed or disagreed with each of their findings,” she said. “Do I not understand what the clear error standard is?”

The issue here, however, isn’t so much whether the Court understands the clear error standard as whether it cares about it. And for years, the conservative justices have been working to keep challenges to gerrymanders, whether partisan or racial, out of courtrooms. Their decision four years ago in Rucho opened the door for a case just like this one: Black people consistently vote for Democrats by overwhelming margins, so effective racial gerrymandering is a very helpful tool for predetermining party control. The ability to reframe impermissible racial gerrymanders as permissible partisan gerrymanders ensures that the gerrymanderers will never have to answer for it.

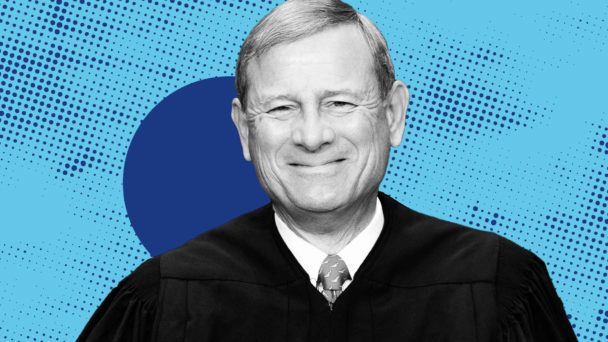

At oral argument, Alito shrugged off concerns about providing legal cover to racist redistricting efforts. The attorney for the South Carolina NAACP highlighted that while Republicans moved people in and out of the district throughout the map-drawing process, somehow, the Black voting-age population, or BVAP, remained constant. Alito was unimpressed. “When race and partisanship are so closely aligned, as they are in fact, why is it surprising that a legislature that is pursuing a partisan goal would favor a map that turns out to consistently have the same BVAP?” he asked. Chief Justice John Roberts characterized the opinion below as resting on “circumstantial evidence” and suggested that the Court would be “breaking new ground” by affirming it, as if 21st-century lawmakers frequently come right out and say “oh boy, I sure do love racism!” when deciding where to draw the district boundaries.

In a pair of high-profile cases last year, the Supreme Court surprised many observers by declining to entirely upend democracy, earning fawning praise from establishment journalists for its restraint. Now, the Court seems primed for a return to its usual democracy-undermining form. Whether lawmakers discriminate against Black voters because they are Black or because they are Democrats, lawmakers are still discriminating against Black voters. A decision for the legislature here would put a political system in which everyone can freely and fairly participate a little further out of reach.