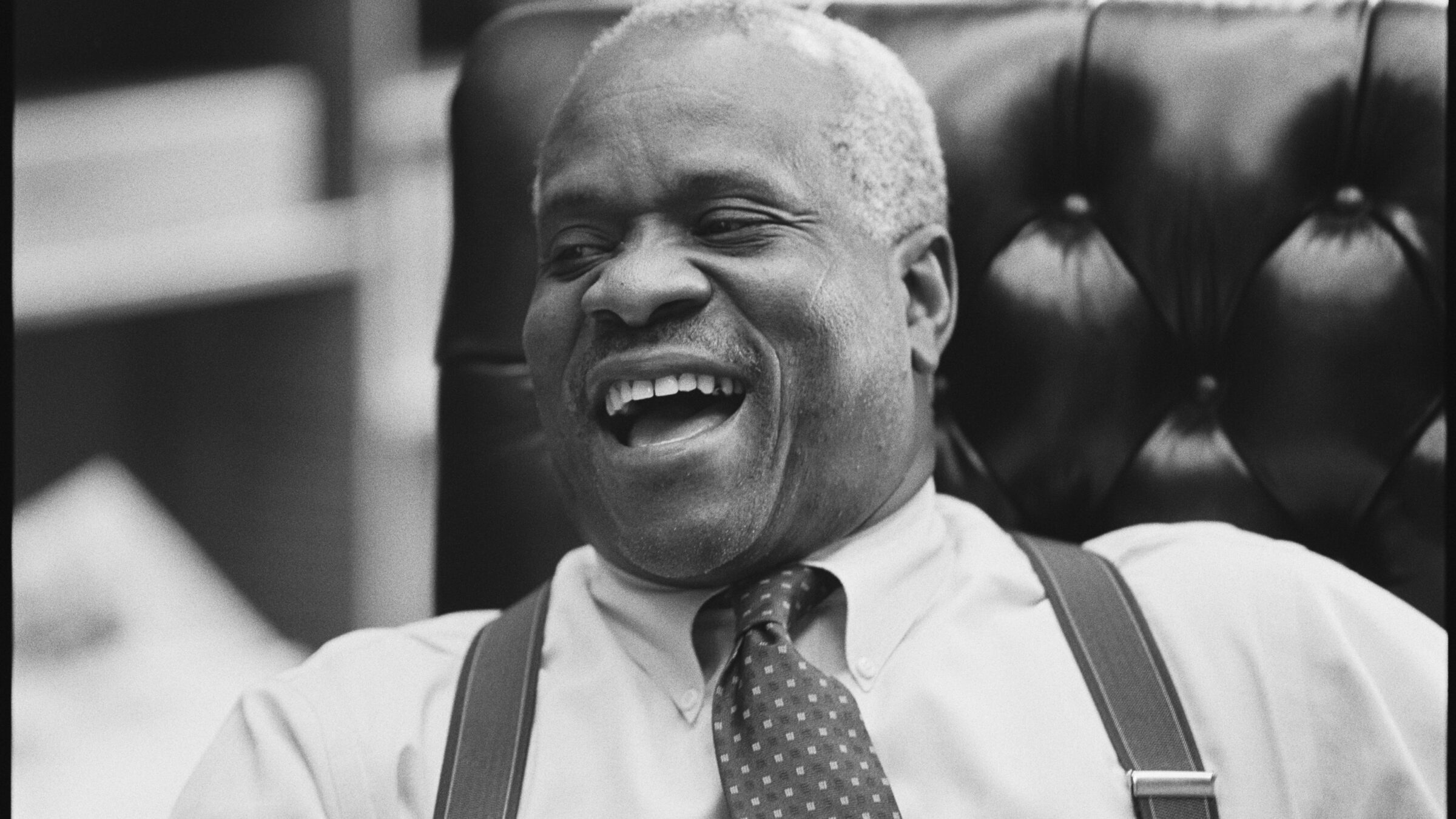

Sixty years ago this month, the Supreme Court decided a case in which it did more to protect the rights of poor Americans than ever before or since. In Gideon v. Wainwright, the Court unanimously held that the Sixth Amendment’s right to “have the Assistance of Counsel” guarantees a court-appointed lawyer to anyone facing serious criminal charges who can’t afford to hire one. Writing for the majority, Justice Hugo Black characterized this conclusion as self-evident in light of the byzantine U.S. legal system that poor people would otherwise have to navigate alone, and the devastating consequences of any missteps along the way.

“In our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him,” Black wrote. “This seems to us to be an obvious truth.”

Gideon forms the backbone of the modern system of public defense in the United States. It is also one of the liberal Warren Court’s most significant accomplishments on behalf of marginalized people, which means that conservatives have spent every moment since raging against its existence. Republican politicians, eager to exploit the reality that people accused of crimes are not exactly a popular constituency, are happy to slash public defense spending in the name of fiscal responsibility. Democrats, terrified of being smeared as soft on crime, are reliably susceptible to pressure to do the same; judges, terrified of being smeared as “activists” for meddling in “policy matters,” are reliably reluctant to do anything about it.

What all this means is that today, the right to counsel outlined in Gideon is effectively an unfunded mandate that no one in a position of power has any real incentive to fulfill. Even more alarmingly, a Supreme Court controlled by a six-justice conservative supermajority is flirting more enthusiastically than ever with the prospect of overruling Gideon—or, at the very least, transforming its aspirational promise into a meaningless platitude.

Ben Shapiro says there’s no federal right to counsel: “The notion that the public has to pay for the counsel is obviously not correct. I mean — if that had been true then it wouldn’t have taken until Gideon v Wainwright to say so” pic.twitter.com/db4qXXcYZw

— Jason Campbell (@JasonSCampbell) March 22, 2023

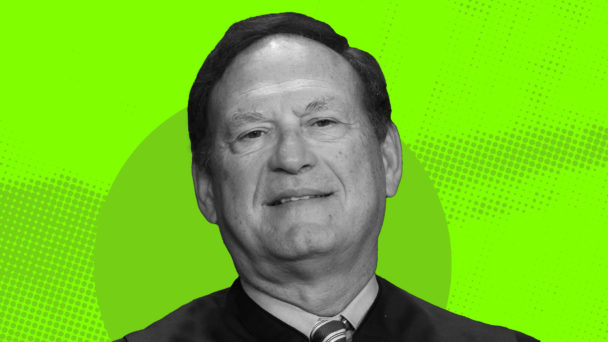

Ben Shapiro is a Newsmax-flavored carnival barker whom no one should take seriously, but this idea has been percolating on the right for years. Perhaps the most ominous shot across Gideon’s bow came in Garza v. Idaho, a 2019 case about the standard defendants must meet to prove that they received constitutionally inadequate assistance of counsel (public defender or otherwise). In dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined in pertinent part by Justice Neil Gorsuch, decided to get ambitious, questioning the legal relevance of the premise on which Gideon rests: that no matter how strong their case, anyone forced to defend themselves against the full power of the state without help has no meaningful chance of prevailing.

Thomas, as Thomas is wont to do, framed his conclusion as a faithful application of originalism, the judicial methodology that purports to interpret the Constitution based on what modern conservatives imagine its words would have meant to the gaggle of slaveholding white men who wrote it some 250 years ago. The Sixth Amendment, Thomas argued, protects the right to hire a lawyer. But since the English common law did not contemplate free lawyers for poor people, he argued, the amendment’s “original meaning” does not require the government to provide you with a good lawyer—or with any lawyer at all. It is remarkable how dependably our nation’s foremost Constitution experts become very wary of its implications the moment it might be deployed to help people they don’t like.

“The right to counsel is not an assurance of an error-free trial or even a reliable result,” Thomas wrote. “It ensures fairness in a single respect: permitting the accused to employ the services of an attorney.”

When someone says “LWOP” (Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)

As always, behind a Republican judge’s soaring paean to originalism is a jumble of right-wing dogma about the social imperative to punish criminals as unsparingly as the Eighth Amendment allows. For example, Thomas asserted that expansions of the right to counsel “directly conflict with the government’s legitimate interest in the finality of criminal judgments,” a common conservative talking point that treats fundamental rights as annoying inconveniences, and violations thereof as an acceptable price to pay for efficiently managed courtroom dockets. In Thomas’s view, the purpose of the legal system is not so much to do “justice” as it is to cycle through disposable people at a pace he deems sufficiently brisk.

Speaking of conservative talking points, Thomas’s dissent also invokes the purported expense associated with Gideon: The Court, he argued, should “hesitate before…imposing additional costs on the taxpayers and the Judiciary.” But the assumption that Gideon burdens taxpayers is, at the very least, dubious, and recent research suggests that fully-funded public defense is actually the prudent financial choice. A decade-long study of the Bronx Defenders, for example, found that its “holistic defense” model saved $165 million just in incarceration costs; a 2016 analysis found that every dollar spent on a similar program in Kentucky saved the state an eye-popping $5.66. With cost savings like these on the table, it is hard not to view Thomas’s argument as his considered policy judgment that spending money on criminals is inherently wasteful, no matter how much the government in fact saves in the process.

The opinion’s most egregious lie, however, is its casual assertion that even without a robust right to counsel, things will inevitably work themselves out, because We As A Society can count on our elected officials to do the proverbial right thing. “History proves that the states and the federal government are capable of making the policy determinations necessary to assign public resources for appointed counsel,” Thomas writes.

This appeal to the invisible hand of federalism is offensively, cartoonishly detached from reality. The Sixth Amendment Center estimates that state and local governments spend $6.5 billion annually on indigent defense, which sounds like a big number until you remember that they spend more than $200 billion every year on police and incarceration. The budgets for prosecutors and district attorneys typically dwarf those of their public defense counterparts, forcing many public defenders to do the work of two or three or more people. Nationwide, some three-quarters of public defenders’ offices exceed recommended caseload limits. A 2017 study found that Louisiana would have to hire 1,769 public defenders in order to provide “reasonably effective assistance of counsel” to everyone who needed it. The actual number of public defenders in Louisiana at the time: 363.

(Photo By Lea Suzuki/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

I do not mean to suggest that Gideon is about to go the way of Roe v. Wade before the end of the current Supreme Court term. Thomas and Gorsuch, the dissenters in Garza, control only two of the Court’s nine votes. Many state constitutions protect the right to counsel independently of the federal Constitution, and in some cases to an even greater extent. President Joe Biden’s efforts to appoint more public defenders to the federal judiciary means that with increasing frequency, the people making decisions about the constitutional adequacy of legal counsel for poor people will have firsthand experience with the real-world challenges that public defenders deal with every day.

That said, the Court in 2023 looks nothing like the Court that decided Garza back in 2019, before the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett yielded the most conservative Court since the Great Depression. Conservative legal scholars have already touted Thomas’s dissent in Garza as a framework for newly-empowered originalist judges to take aim at non-originalist decisions that might be in jeopardy. As the fallout from Roe’s death demonstrates, states are hardly reliable defenders of legal rights that federal courts abandon. The quixotic Thomas opinions of a few years ago have a funny way of turning into full-blown majorities on the history-and-tradition-happy Barrett Court. Given its members’ demonstrated disinterest in upholding precedents they have the votes to overturn, I would not bet on a full-throated reaffirmation of Gideon anytime soon.

The hollowing out of Gideon’s promise tracks the broader collapse of America’s social safety net, which elected officials are always quick to strip for parts in order to fund a new police headquarters, a deeper tax cut, or another multibillion-dollar defense contract. But in a country where four of every five people charged with crimes rely on public defenders to represent them, the consequences of this greed are especially tragic. Every decision that weakens the right to counsel means that more people will waste more years languishing in prison—years they could have avoided with just a few more hours’ worth of help.

The implicit message of Gideon is that the lives of marginalized people are valuable. The explicit message of its disappearance is that they are not.