The government of Utah has long been about as Republican as governments can get. The governor, Spencer Cox, is a Republican, as are both U.S. senators and all five statewide elected officials. Republicans hold supermajorities in both the Utah House and Utah Senate, and have controlled both chambers for almost five decades. The last time Utah had a Democratic governor, the president was Ronald Reagan. The last time a Democratic candidate won a Senate seat in Utah, Mitt Romney had not yet graduated from college.

But as demonstrated by the last decade or so of Republican politics—choosing Romney as the party’s presidential nominee in 2012, and Donald Trump in every election since—not all Republicans see eye-to-eye all the time. And in Utah, there is real beef between Republican lawmakers, who have gleefully adopted the reactionary policy agenda championed by the national party, and the justices on the Utah Supreme Court, who have not.

All five sitting justices were nominated by Republican governors and confirmed by Republican Senate majorities—in the case of the longest-tenured justice, in 2000, and in the case of the most junior justice, only two months ago. But last year, the Utah Supreme Court—at the time, three women and two men—voted 4-1 to uphold a lower court injunction that temporarily blocked the legislature’s near-total abortion ban from taking effect. The state’s two highest-ranking legislators, Senate President J. Stuart Adams and House Speaker Mike Schultz, responded by accusing the justices of “undermining the constitutional authority of the Legislature to enact laws as elected representatives of the people of Utah.”

Protesters gather outside the Utah State Capitol to show support for Roe v. Wade, May 2022 (Photo by George Frey/Getty Images)

Also in 2024, the Utah Supreme Court halted Republican legislators’ hamfisted attempts to ignore the will of their (largely Republican) constituents and gerrymander themselves in office in perpetuity. Back in 2018, Utah voters passed Proposition 4, a ballot initiative that created an independent commission to draw fair maps for state and congressional legislative districts. Republican lawmakers, furious at the thought of no longer being able to pick their voters, quickly passed a law to alter Proposition 4 by limiting the commission’s authority. But the Utah Supreme Court struck down that law as unconstitutional, holding that “when Utahns exercise their right to reform the government through a citizen initiative, their exercise of these rights is protected from government infringement.”

Adams and Schultz called that decision, League of Women Voters of Utah v. Utah State Legislature, “one of the worst outcomes we have ever seen from the Utah Supreme Court,” and began pushing a ballot initiative in 2024 that would, if passed, overrule League of Women Voters of Utah by amending the state constitution to allow lawmakers to modify or repeal voter-approved initiatives. But the justices stopped that more roundabout effort to gut Proposition 4, too, upholding Third District Judge Dianna Gibson’s finding that the initiative’s language was so misleading that Utahns had “no meaningful right to vote” on it.

In the context of the Republican Party’s frantic efforts to re-gerrymander red states at President Trump’s behest before the 2026 midterm elections, the legal fight over Proposition 4 has national implications. Currently, Utah’s four members of Congress are all Republicans. The district boundaries for next fall have yet to be finalized, but thanks largely to the Utah Supreme Court’s efforts to protect Proposition 4 from Republican meddling, that map will likely include at least one congressional district that favors a Democratic candidate.

Utah Republicans have responded to this string of courtroom losses by trying to hollow out the co-equal branch of government that delivered them. Earlier this year, lawmakers proposed a bill that would constrain lower court judges’ ability to prevent allegedly unconstitutional laws, like the abortion ban, from taking effect during litigation. They also passed a law that stripped the justices of their ability to select their chief justice and transferred it to the governor, subject to confirmation by the Utah Senate. Cox, who’d previously said he had “no interest” in having this power, promptly signed the bill into law.

Some Republicans have even begun threatening to impeach Gibson, the judge who voided their retaliatory ballot initiative in 2024. Last month, Gibson earned a fresh round of vitriol when she rejected a GOP-proposed map as inconsistent with Proposition 4’s requirements, and instead ordered the adoption of a map that creates a solid Democratic district around Salt Lake City. Adams, the Senate president, characterized Gibson’s map as “the most partisan and thus the most gerrymandered map in the history of the state of Utah,” because in his mind, a gerrymandered district is any district where a Republican does not win in a blowout.

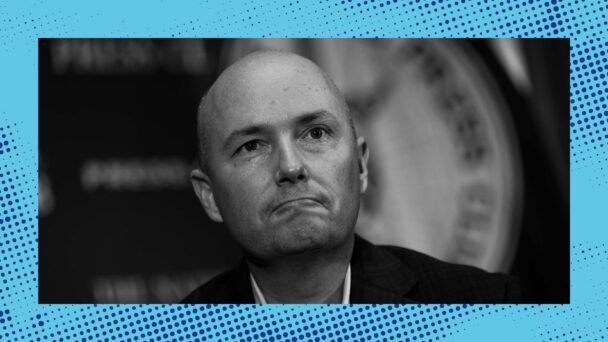

Last week, Governor Cox announced his support for yet another punishment for the Utah Supreme Court: expanding it from five justices to seven. When lawmakers floated that idea just a few months ago, Cox equivocated; now, he said, he’s concluded that expansion “probably makes sense.” It is part of a strategy that has become increasingly popular among Republican elected officials when a court enforces the law in a way Republicans do not like: disciplining that court in an effort to guarantee its future compliance.

At a press conference, Cox acknowledged the Utah legislature’s frustration with the Utah Supreme Court, but rejected the notion that he wanted to add seats in order to “pack” it. (“Packing,” I guess, is only when Democrats want to do it.) Instead, Cox said that he wants to get “more resources” to justices and judges, arguing that cases take too long to wind their way through the system. “We’re not the state we were 40 years ago. We’re not the state we were 20 years ago, from a size perspective,” Cox said. “There’s a reason most medium-sized states to larger states start to move to the seven-to-nine justice range.”

But the timing of Cox’s interest in the provision of judicial resources is, to put it generously, odd: As the Salt Lake Tribune points out, the Utah Supreme Court has issued 60 opinions this year, well ahead of last year’s total of 47 and a major jump up from the 27 decisions it issued in 2023. And Chief Justice Matthew Durrant, who joined the Utah Supreme Court 25 years ago, has warned that a larger court would probably take more time, not less, to issue its decisions. In February, Justice Paige Peterson called it “absolutely false” to assert that the Court needs more justices to address an alleged backlog. “We haven’t had a backlog for years,” she said.

Cox, in other words, is claiming to want to solve a nonexistent problem with an ineffective solution—a solution that would just so happen to give angry Republicans two more chances to ensure that next time they want to implement a law of dubious constitutionality or gerrymander voters out of electoral existence, they will do so before a friendlier audience.

Cox tried to head off this argument last week, asserting that because the current justices are all Republican nominees, it would be “weird” to frame expansion as motivated by a desire to change the Court’s ideological composition. But there are meaningful differences between ambitious Republican lawyers from a decade ago and ambitious Republican lawyers today: With increasing frequency, aspiring judges are not products of the conservative legal establishment, but are instead aggressively online culture warriors who cannot bring themselves to say that January 6 was bad or that Donald Trump is capable of breaking the law. In a state as dominated by Republicans as Utah is in 2025, no one is earning serious consideration for a Utah Supreme Court seat by saying anything different.

(Photo by George Frey/Getty Images)

Unlike the nominations process for federal judges, which is entirely up to Trump and the Republican-controlled Senate, Utah’s process includes a few measures intended to blunt the impact of ideology and partisanship: For example, state law requires the governor to select Supreme Court nominees from a list of names provided by a bipartisan commission. But well-intentioned checks and balances like these can only do so much: The governor appoints the commissioners, and anyone he picks for a judicial vacancy must be confirmed by Utah Senate’s far-right Republican supermajority, which makes it unlikely that some moderate rule-of-law enthusiast gets the nod.

The reality of modern Republican judicial politics is that any contender who makes it all the way through the process will push the Utah Supreme Court to the right, bringing the institution more in alignment with GOP lawmakers who fervently believe that legal limitations on their power are inherently illegitimate.

In January, Durrant tried to defuse the tension at a joint session of the Utah House and Senate, urging disgruntled lawmakers not to retaliate any further. Judges, Durrant said, must be “free to make decisions driven by the law and the facts and not based on who the litigants are and how they might react to those decisions.” He acknowledged the inevitability of disagreement, but warned that “the people of Utah will judge the integrity of both our institutions and our commitment to the rule of law, not by what we do and say when we agree, but by the respect we show each other when we disagree.”

It is a nice enough sentiment, but Durrant’s mistake was assuming that his audience shared it. Republican lawmakers do not want judges and justices to “make decisions driven by the law and the facts,” or to demonstrate a “commitment to the rule of law.” Republican lawmakers want judges and justices who share their agenda, and will rule as they ask.