On January 17, the North Carolina Judicial Standards Commission announced that it had closed an ethics investigation it never should have opened. Last summer, the commission targeted State Supreme Court Justice Anita Earls after an interview with Law360 in which she made candid, correct statements about the overwhelming whiteness of the legal system and the impact that has on the law. “Our court system, like any other court system, is made up of human beings,” said Earls, the only Black person on the state’s high court and one of just two Democrats. “I believe the research that shows that we all have implicit biases.”

Under normal human standards, this evaluation would not be controversial. The state’s appellate judges and the attorneys who appear before them are over 90 percent white and 60 percent male, even though white guys are only a third of the state’s population. A committee was established in 2020 to look into the supreme court’s hiring practices and diversity, but Republicans quickly disbanded it when they flipped the court.

Under North Carolina’s judicial standards as interpreted by the Republican-controlled commission, however, Earls’ evidence-backed statements warranted an ethics complaint and threat of disciplinary action. Earls filed a lawsuit in August to put a stop to the investigation. Now that the Commission has dropped the matter, Earls has voluntarily dismissed her case, too. “I continue to believe that the First Amendment protects my ability to speak about matters of racial equity in the legal system,” she said in a statement. State lawmaker Marcia Morey, who defended Earls’ comments as constructive criticism, said the Commission’s dismissal “signals that Justice Earls has every right to speak out on issues.”

This vindication of Earls affirms what should have been obvious all along: Acknowledging systemic injustice is a necessary precursor to doing anything about it. Yet the Commission’s investigation was premised on the idea that Earls’ acknowledgement of systemic injustice, not the systemic injustice itself, was the real problem.

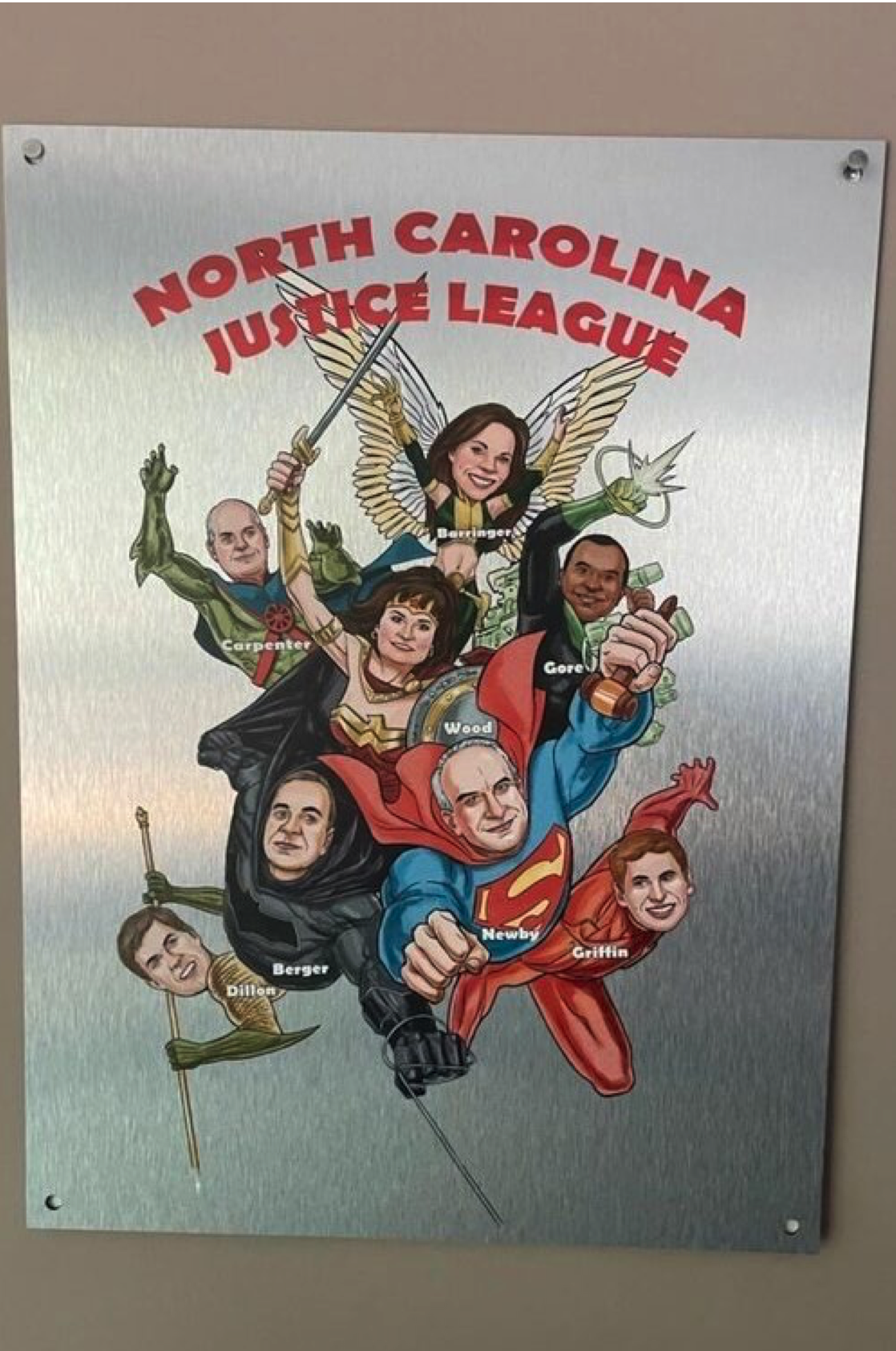

Some of the goofier aspects of this story make clear how hollow the critique was. Earls’ white Republican colleagues took umbrage at the suggestion that they could, even unconsciously, be “acting out of racial, gender, and/or political bias in some of their decision-making.” Mind you, an illustration of those same colleagues hangs in the Supreme Court building, labeled “North Carolina Justice League” and portraying the Republican justices as superheroes. It’s unbearably silly for the court’s Republicans to clutch pearls about allegations of political bias while simultaneously imagining themselves as costumed defenders of partisan gerrymandering.

The Commission’s focus on Earls was also a needless distraction from actual issues of judicial misconduct. Billy Corriher recently wrote in Slate about how unserious it is that Earls’ conduct raised the possibility of ethics enforcement, but clear-cut ethical breaches by other state judges did not. The rules say that state judges can’t make personal financial contributions to political candidates, for instance, yet there’s been no action against state Supreme Court Chief Justice Paul Newby for donating to Republican candidates willy-nilly. (Don’t get me started on the United States Supreme Court.)

The stated reason for the Commission’s investigation was that Earls may have violated the state’s judicial ethics code by not conducting herself “in a manner which promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.” But the unstated reason was: She hit too close to home, and devotees of the broken status quo wanted to shut her up. They failed.