Last month, a New York jury ordered Donald Trump to pay $83 million to longtime magazine columnist E. Jean Carroll to compensate her for the harm he caused by lying about what he did to her nearly 30 years ago, when he sexually assaulted her in a Bergdorf Goodman dressing room.

The verdict was a ray of hope for those who fear that Trump will never be held accountable for any of his various misdeeds. But even setting aside its political impact in 2024, Carroll’s verdict was an important example of something that should happen more often in the American legal system: an individual successfully holding a wealthy person or corporation accountable for having wronged them. And a big part of the reason so many normal people can’t get justice in court is the United States Supreme Court.

In 1971, a corporate lawyer named Lewis Powell wrote a memo calling on the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to step up their efforts to influence the judiciary, which he called “the most important instrument for social, economic and political change.” A few months later, President Richard Nixon nominated Powell to the Supreme Court, and for the several decades that followed, the business community took Powell’s exhortations to heart. The protect-the-powerful march of the Supreme Court has had its desired effect, making the road to a jury verdict an obstacle course that can be, at best, difficult to navigate.

E. Jean Carroll leaves Manhattan Federal Court, January 2024 (Photo by GWR/Star Max/GC Images)

Consider several aspects of the legal system that made Carroll’s verdict possible. First, Carroll had the ability to go into court, point the finger at someone wealthy and powerful, and say: You did something wrong to me, and need to make amends. Second, Carroll’s claims were decided not by a judge, who are often men used to power, but instead by a jury—people from different walks of life, who might better understand the difficulties of fighting back against reputational smears. And finally, the jury had the ability to send a message to Trump, awarding Carroll damages not only for her pain and suffering, but also tacking on “punitive damages”—an amount the jury deemed necessary to deter Trump and other potential wrongdoers.

The problem is that in recent years, the Supreme Court has gutted these features of the civil justice system—access to court, trial by jury, and ability to recover a meaningful damages award—in a series of landmark cases in which the Chamber-of-Commerce wing of the Court came out on top. When the choice was between the interests of powerful people and those of regular folks, powerful people won every time. People like Carroll can still get justice, but not as often as they should.

Start with access to courts. In the 2001 decision Circuit City v. Adams, a 5-4 Supreme Court greenlit corporate America’s new strategy for avoiding accountability from workers (and consumers): forcibly removing disputes from public courts to private arbitrators. This fine print is in both the terms that you click before using a new app and the forms that you sign when taking a new job: Any disputes must go to arbitration, where the damages available are far lower, and where arbitrators have lots of incentive to go easy on corporate defendants. By one estimate, 98 percent of workers who could bring employment claims don’t bother when arbitration is the only option.

Even if plaintiffs can get into court, there’s no guarantee they get a jury. In Twombly and Iqbal, a pair of cases decided in the late 2000s, the Supreme Court made it easier for judges to dismiss cases before plaintiffs get to discovery—the documents and depositions that make it possible to prove a case. This came after the Court, in a 1986 trilogy of cases, made it easier for judges to throw out other cases on “summary judgment”—after discovery but before they go to the jury. It’s not surprising that the percentage of federal civil cases decided by a jury trial has declined from 5.5 percent in 1962 to 0.53 percent in 2019, with a similar trend in state courts as well.

Finally, in a pair of cases in 1996 and 2003—one where BMW lied to consumers that its cars were brand new, the other where State Farm put an elderly couple at risk of losing their home as part of a coprprate scheme to limit insurance payouts—the Court invented a constitutional due process right for corporations to use as a shield from “too big” punitive damages awards. (In other words, protection from too much accountability for the harm they cause.) This protection came at the urging of the business community, and faced dissents from both Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the left and on the right from Justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia, who objected that punitive damage awards “represent the assessment by the jury, as the voice of the community, of the measure of punishment the defendant deserved.” And the business community’s campaign against punitive damages “run wild” got an additional boost from Exxon-funded research on the issue— an interest that developed when the company was forced to pay for the consequences of running the Exxon Valdez aground in Prince William Sound.

The justices on the Court have changed over the years, but the upshot of the cases it decides has not: The institution works to minimize the role of the civil jury as a democratic institution, and protect the wealthy and powerful from meaningful accountability.

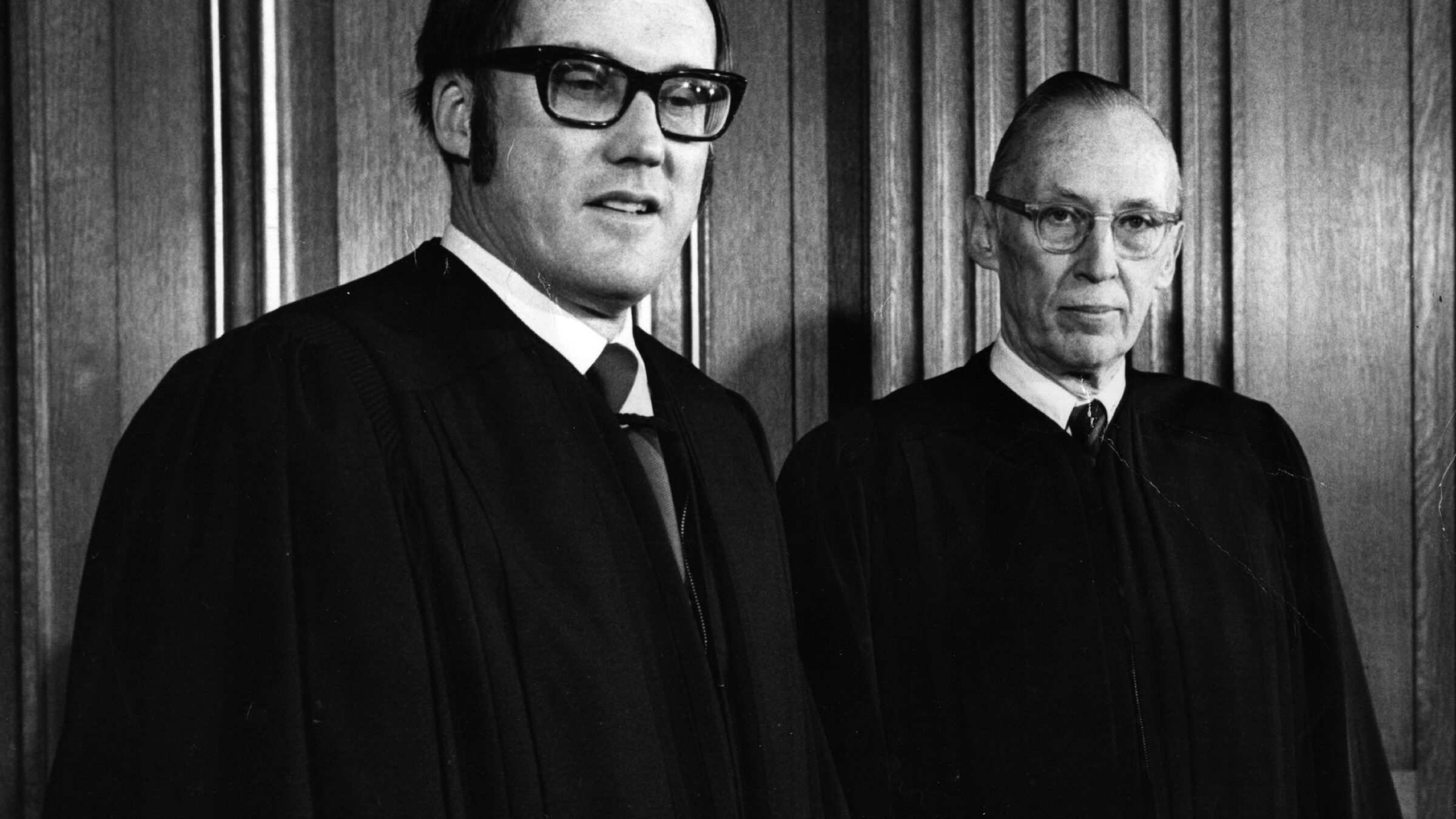

Justices William Rehnquist and Lewis Powell, January 1972 (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

The week after E. Jean Carroll’s verdict, Jennifer Harris, a former FedEx sales manager in Houston, got bad news. In 2022, Harris, a Black woman, had won a $366 million verdict against FedEx for retaliating against her when she complained about race discrimination by her white manager. At trial, Harris argued that FedEx had cut corners and short-staffed HR, failing to establish a system that could ensure consistent treatment of employees and allowing the biases of individual managers to go unchecked. But on appeal, the Fifth Circuit wiped out most of the damages, reducing the number from $366 million to just $248,619, primarily on the grounds that FedEx made “good-faith efforts” to comply with federal law. (Disclosure: I worked on an amicus brief supporting Harris in this appeal).

“The Supreme Court works to minimize the role of the civil jury as a democratic institution, and protect the wealthy and powerful from meaningful accountability.”

In her fight for justice, Harris faced key obstacles Carroll did not. First, FedEx made its employees agree to raise any disputes about their employment contracts within six months. As with forced arbitration, this corporate tactic weaponizes courts’ willingness to enforce “contracts” that are far from genuine agreements between both sides. Indeed, Harris had to sign the form as a condition of applying for a job at FedEx, where negotiation is really out of the question. No problem, the Fifth Circuit said.

That left Harris’ employment discrimination claim, where Harris had to contend with the Fifth Circuit’s use of “remittitur”—a judge’s power to reduce a jury verdict if they think it is “clearly excessive.” After pay lip service to the “strong presumption” given to upholding a jury’s damages award, Judge Cory Wilson’s opinion for the court looked at ostensibly comparable cases and decided that even $300,000 was “excessive.” That final step left Harris with just 0.07 percent of what her peers awarded her.

Harris’s jury in Houston tried to do what Carroll’s jury did in New York: act as the voice of the community and issue a damages award that would be large enough to change a misbehaving defendant’s behavior. But for a megacorporation like FedEx, a quarter-million dollars is just the cost of doing business, and a small one at that.

E. Jean Carroll’s verdict is well worth celebrating. But it is the exception, not the rule. The Supreme Court has given powerful defendants too many opportunities to escape justice, and the legal system is worse for it.