In November 2020, Justice Samuel Alito took to the (virtual) stage at the Federalist Society’s annual conference and went on a tirade. He complained about the tyranny of COVID-19 restrictions, decried state laws facilitating access to Plan B (incorrectly claiming that it “destroy[s] an embryo after fertilization”), and bemoaned the fact that opposition to gay marriage was now widely viewed as bigotry. “Religious liberty,” he claimed, “is fast becoming a disfavored right.”

It was an odd time for Alito to be complaining. Just a few weeks prior, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had died, and Amy Coney Barrett now sat in her seat. A slim Supreme Court conservative majority had become a 6-3 supermajority, and Alito himself was more powerful than he had ever been. Out of reach for half a century, the conservative legal movement’s longstanding goals, from overturning Roe v. Wade to dismantling the administrative state, were now well within reach. But to hear Alito tell it, conservative principles were under siege, beset on all sides by liberal cultural and political forces.

Alito has kept the grievances flying. Last April, he sat down for an interview with The Wall Street Journal, which he appears to be using as his unofficial PR arm, to complain about public criticism of the Court, claiming that “this type of concerted attack on the court and on individual justices” is “new during my lifetime.” (It almost feels beside the point to note that this simply isn’t true—Earl Warren’s tenure as a progressive chief justice spawned an extensive and coordinated political resistance, including an “Impeach Earl Warren” campaign led by his conservative opponents).

“Yes I’ll do the FedSoc address but only if we can film it in the style of a hostage video” (Clip via YouTube)

A few months later, when Alito found out that ProPublica planned to report on a billionaire-funded 2008 vacation that he never disclosed, he took to the pages of the Journal to claim that ProPublica “misleads its readers” before even seeing the contents of the piece. In September, after public calls for Alito to recuse himself in a case where one of his IWSJ interviewers was an attorney, he made an unusual and caustic public statement, claiming that his critics “fundamentally misunderstand” that judges can be trusted to “put favorable or unfavorable comments and any personal connections with an attorney out of our minds and judge the cases based solely on the law and the facts.”

It’s not just Alito. Leonard Leo, the longtime Federalist Society co-chairman and kingmaker of the conservative legal movement, recently spoke at a gala sponsored by the Catholic Information Center, claiming that “Catholicism faces vile and immoral current-day barbarians, secularists, and bigots” and ranting about “woke idols” and the “progressive Ku Klux Klan.” This sort of rhetoric should be familiar to anyone who lived through the administration of Donald Trump, who spent much of his time as the most powerful person on Earth claiming to be the victim of “presidential harassment” and other non-traditional crimes.

At first glance, the cycle here might seem obvious. Conservatives acquire power, do conservative things, receive criticism, and become upset. But that underestimates the role that this perceived victimhood has played in conservative politics, and the conservative legal movement in particular.

From its founding in 1982, the Federalist Society, now the preeminent conservative legal organization, was motivated by a sense of marginalization among conservative law students and academics. By their own account, law school campuses were rife with liberals—students and professors alike. In their initial proposal for a conservative legal conference, the students wrote that “law schools and the legal profession are currently strongly dominated by a form of orthodox liberal ideology which advocates a centralized and uniform society.”

At the time, they weren’t entirely off base. By most accounts, law schools in the early 1980s were predominantly liberal, and conservative legal orthodoxies were in their infancy. It was that sense of otherness (and a few hundred thousand dollars of right-wing billionaire largesse) that propelled the Federalist Society’s growth in its early years.

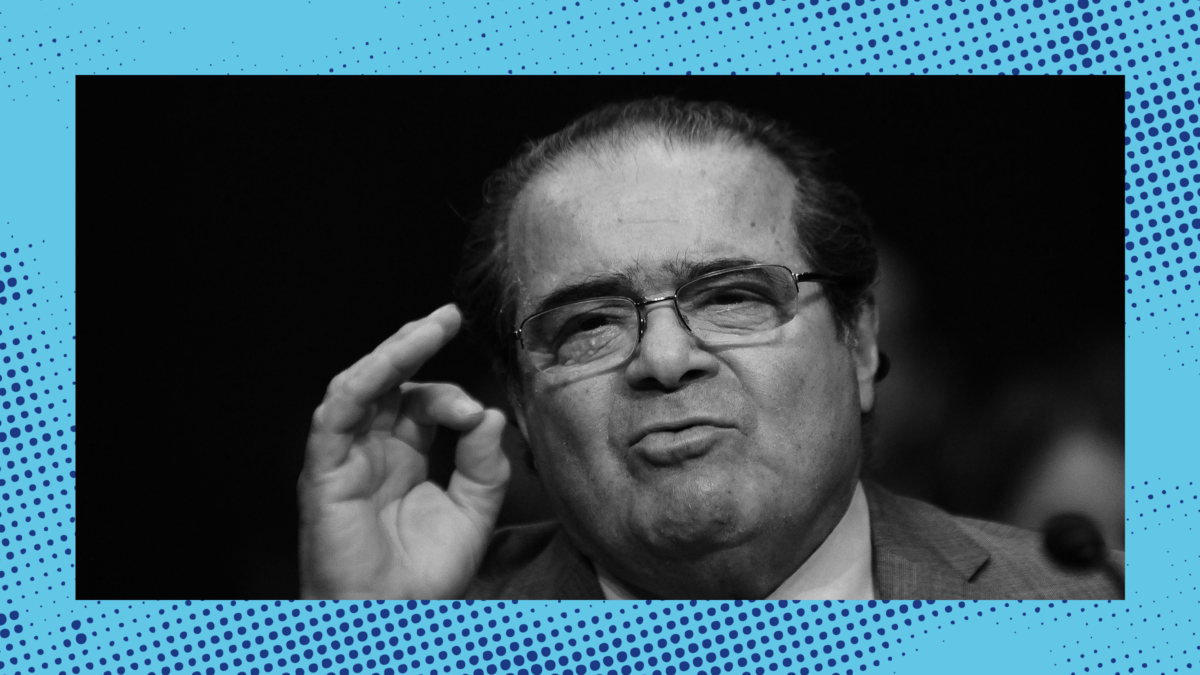

The sense of marginalization persisted even as the organization and the broader movement grew increasingly influential. In 1987, longtime Federalist Society collaborator and movement scion Robert Bork was nominated to the Supreme Court, only for the Senate to scuttle his appointment after he testified to a set of beliefs that were in equal measures vile and reviled. Steven Teles, who wrote a book about the ascendance of the conservative legal movement, described Bork’s rejection as a galvanizing moment for the organization. It was confirmation of everything they already knew: Conservatives in the law were outcasts, under attack by liberals on every front. The fact that another rigid conservative and longtime Federalist Society ally, Justice Antonin Scalia, had been unanimously confirmed to the Supreme Court the year prior didn’t shake their convictions.

When Borking is afoot but you did it to yourself (Photo by © Wally McNamee/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

In the ensuing decades, the Court was probably best described as moderately conservative. It would gift George W. Bush the presidency in 2000. It crafted an individual right to gun ownership in District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008. It opened the floodgates to unfettered political spending in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. It hollowed out the core enforcement provision of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder. There were occasional liberal wins, to be sure—conservatives were particularly bitter about the establishment of protections for LGBTQ rights—but the Court was decidedly conservative, anchored by Justice Anthony Kennedy, a Republican with only sparing liberal tendencies.

Yet Scalia himself, by then the conservative legal movement’s guiding light, was unsatisfied. “The whole time I have been on my Court, it has been a liberal Court,” he said in 2015. (Forgive him the Freudian slip, surely he meant to say “the Court.”) Even when his cohort was decidedly winning, Scalia insisted that it wasn’t.

Pictured: truly loathsome lawyers, and also Rudy Giuliani (Photo by Nancy Ostertag/Getty Images)

There is vision here into the machinations of the reactionary brain. They are not merely sensitive to criticism or disagreement. Grievance runs in their veins. It fuels their politics and propels their movements. They cannot operate without it. The Italian writer Ignazio Silone famously described fascism as “a counterrevolution against a revolution that never took place.” Scalia was not a fascist, though that may have been mostly because history never afforded him the opportunity. Nor is the Federalist Society quite a fascist organization, although the organization’s deep ties to the insurrectionist movement and embrace of antidemocratic legal principles makes it a matter of debate.

But there is an impulse in reactionary thought to manufacture the image of a wildly powerful enemy. It serves as a reason to mobilize, and creates a permission structure for the horrible things that must be done in response. The stronger the foe, the more aggressively power must be wielded to fight it.

In between the lines of Scalia and Alito’s perpetual whining is a mission statement. It’s not enough to win most of the time. You have to win all of the time. And when you do, your critics should be silent.