A few weeks back, the Supreme Court quietly declined to hear Fitisimanu v. United States, leaving in place one of the most explicitly racist jurisprudential regimes in American law.

Fitisimanu was a direct challenge to the Insular Cases, a set of Supreme Court cases dating back to 1901, following the Spanish-American War, that established the scope of the constitutional rights held by citizens of America’s newly acquired territories in Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The Court’s rulings firmly established the residents of those territories as secondary citizens, with fewer constitutional protections than citizens of established states. While residents would receive certain fundamental rights—the Court did not clarify which—the rest were to be dictated by Congress as it saw fit.

Unlike the mostly-veiled racism of modern Supreme Court cases, the racism of the Insular Cases was explicit. Moreover, it was fundamental to the holding of the cases. One case, Downes v. Bidwell, found that “the administration of government and justice according to Anglo-Saxon principles may for a time be impossible” in territories inhabited by “alien races.” Another referred to residents of Puerto Rico as members of “savage tribes.”

It was on that basis—the idea that different races required different governing structures—that the Court denied the residents of the annexed territories the full protection of the Constitution. In other words, this was not the sort of incidental racist language that might make its way into other Supreme Court decisions from the era. The belief that the residents of these territories should be treated differently because they are of a different race was central to the Court’s reasoning. The Philippines became an independent nation in the wake of World War II, but the Insular Cases form the basis for the legal regime that governs the United States’ relationships with Puerto Rico and Guam to this day.

The legal apartheid established by the Insular Cases left the citizens of the newly-annexed territories with a patchwork of rights. While Congress has passed laws making them U.S. citizens (meaning they can, for example, travel and work freely throughout the country), they are effectively shut out of the federal democratic process: They cannot directly participate in presidential elections, and have only symbolic representation in Congress.

Limits on voting rights are only one of a parade of inequities. The territories have historically received lower levels of Medicaid funding than states, and just this year the Court held that Puerto Rican residents could be excluded from certain federal income benefits. The territories’ subjugated status has even affected the ongoing debt crisis in Puerto Rico—in 2016, the Supreme Court nullified a Puerto Rican law passed to help the government escape its then $20 billion in public debt, holding that unlike states, Puerto Rico did not have the right to authorize its local municipalities to file for bankruptcy.

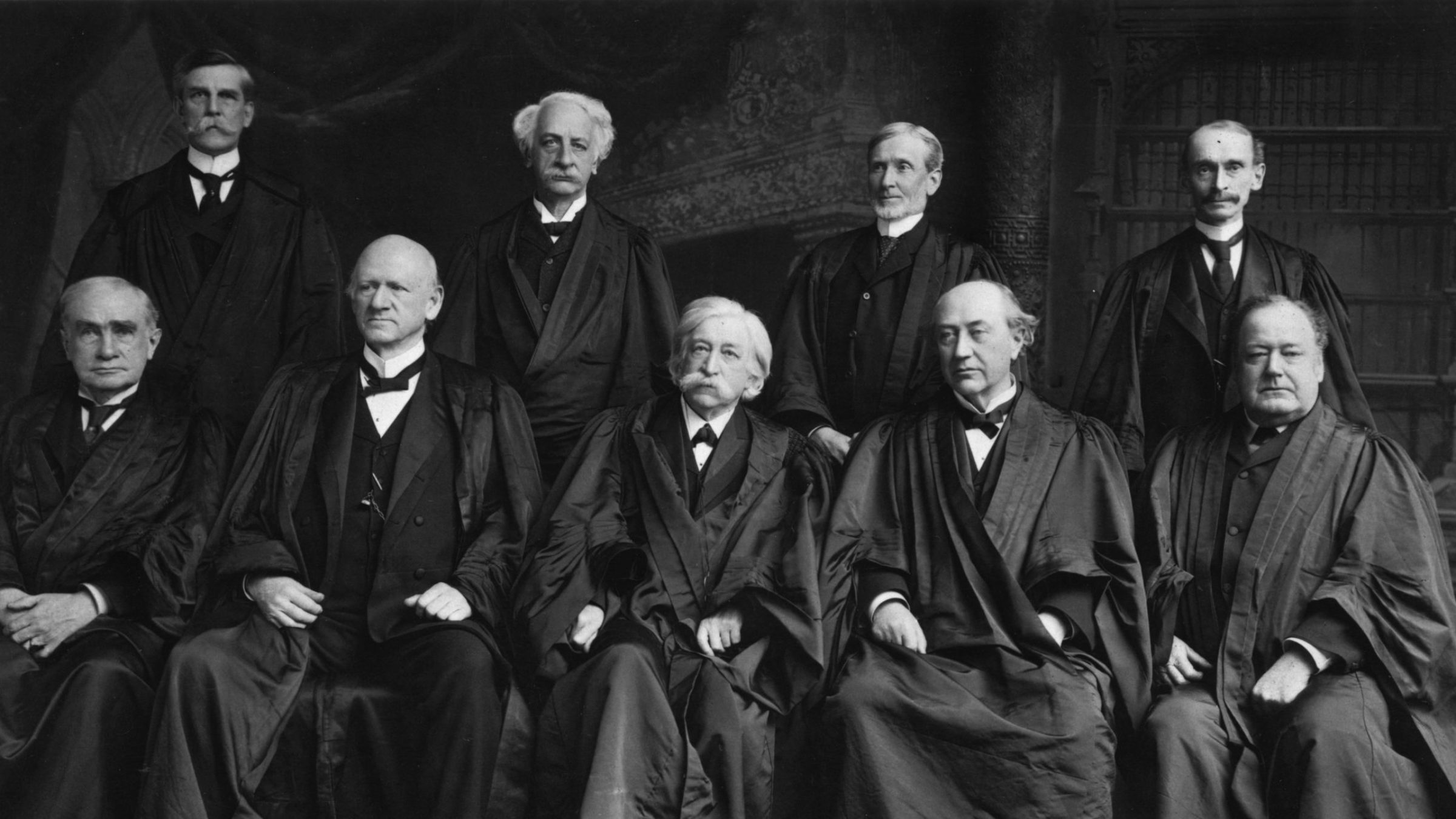

The Supreme Court in 1904; Justice Henry Billings Brown, author of the plurality opinion in Downes v. Bidwell, is at front left (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

American jurisprudence is designed to protect the status quo. Lawyers speak highly of the idea of judicial restraint and its attendant principles: To name a few, stare decisis (the respect for precedent), the narrow tailoring of judicial opinions (the avoidance of decisions with unnecessarily broad impact), and constitutional avoidance (the idea that judges should avoid deciding cases on constitutional grounds if they can find another way to do it). Together, these doctrines operate to discourage judges from causing substantial and unpredictable shifts in the state of the law. Judges who use their position to engage in more proactive efforts to right jurisprudential wrongs are in turn decried as judicial activists, engaged in policymaking rather than the practice of law.

We’re taught that there is wisdom in this rigidity. Legal analysis must be careful and measured, after all, and the judiciary should be wary of causing any major shifts in public policy. But the 120-year reign of the Insular Cases shows the consequences of inflexibility. The web of doctrines purporting to restrain judges can make it difficult to disentangle ourselves from past injustices. What’s more, it provides judges with intellectual cover when they quietly wish to see those injustices perpetuated.

Our history is littered with grotesque Supreme Court cases. Some are no more than the vestigial remnants of old political and cultural regimes, cautionary tales relegated to constitutional history lessons. Others quietly comprise the foundations of our modern government. In 1889, Chae Chan Ping v. United States, the so-called Chinese Exclusion Case, upheld the overtly racist Chinese Exclusion Act, reasoning that “foreigners of a different race” might not readily assimilate into American society. The case is not an anomaly—it helped lay the foundations of our modern immigration jurisprudence, where the judiciary gives heavy deference to the whims of the federal government. In 2018, the Supreme Court carried the case’s racist legacy forward in Trump v. Hawaii, upholding a Trump administration immigration policy that began as a plainly stated attempt to forbid Muslims from entering the country. Chae Chan Ping wasn’t cited, but the line between the cases is easily traced.

Underlying Chae Chan Ping and the Insular Cases is a single phenomenon. What begins as open racism is obfuscated by legal process over time, eventually presenting itself as pragmatic, reasoned policy. Its machinations become ingrained into our government’s structure, and the ability of courts to intervene wanes. A better system would force the Court to either defend or denounce the de facto racial caste system it created over a century ago. In ours, the Court quietly declined review, content to rely on whatever deniability it’s afforded by abstract notions of judicial restraint.

The Court will spend much of this term addressing racial injustice. With six conservatives at the helm, it is likely to deal a death blow to affirmative action in higher education, and further erode the remedial capacities of the Voting Rights Act of 1964. They’ll do so while claiming that they are serving the interests of equality under the law. But the conservative commitment to racial equality has always been a smirking half-truth, designed to weaken remedies for discrimination while its structural underpinnings are left to calcify. Whatever lip service the Court gives to equality as a principle, its decision to leave a system of explicit racial tiers enshrined in our law shows how shallow its rhetoric really is.