The end of the most recent Supreme Court term kicked off what has quickly become a cherished tradition for America’s legal journalists: the race to publish breathless term recaps declaring that all is well inside the four walls of the Court’s marble palace. Article after early-summer article reassured readers that predictions of the most conservative Court in decades ruthlessly crushing democracy had proved histrionic and unfounded.

“America’s Supreme Court is less one-sided than liberals feared,” proclaimed a headline in The Economist on June 24, a week before the Court actually concluded its term. In The New York Times, Adam Liptak reported that the Court’s conservative wing was “badly fractured,” and that the liberals were on a “surprisingly good run.” ABC News declared that even after Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation, the Court had “defied critics” with a “wave of unanimous decisions” and a display of “astonishing bonhomie.”

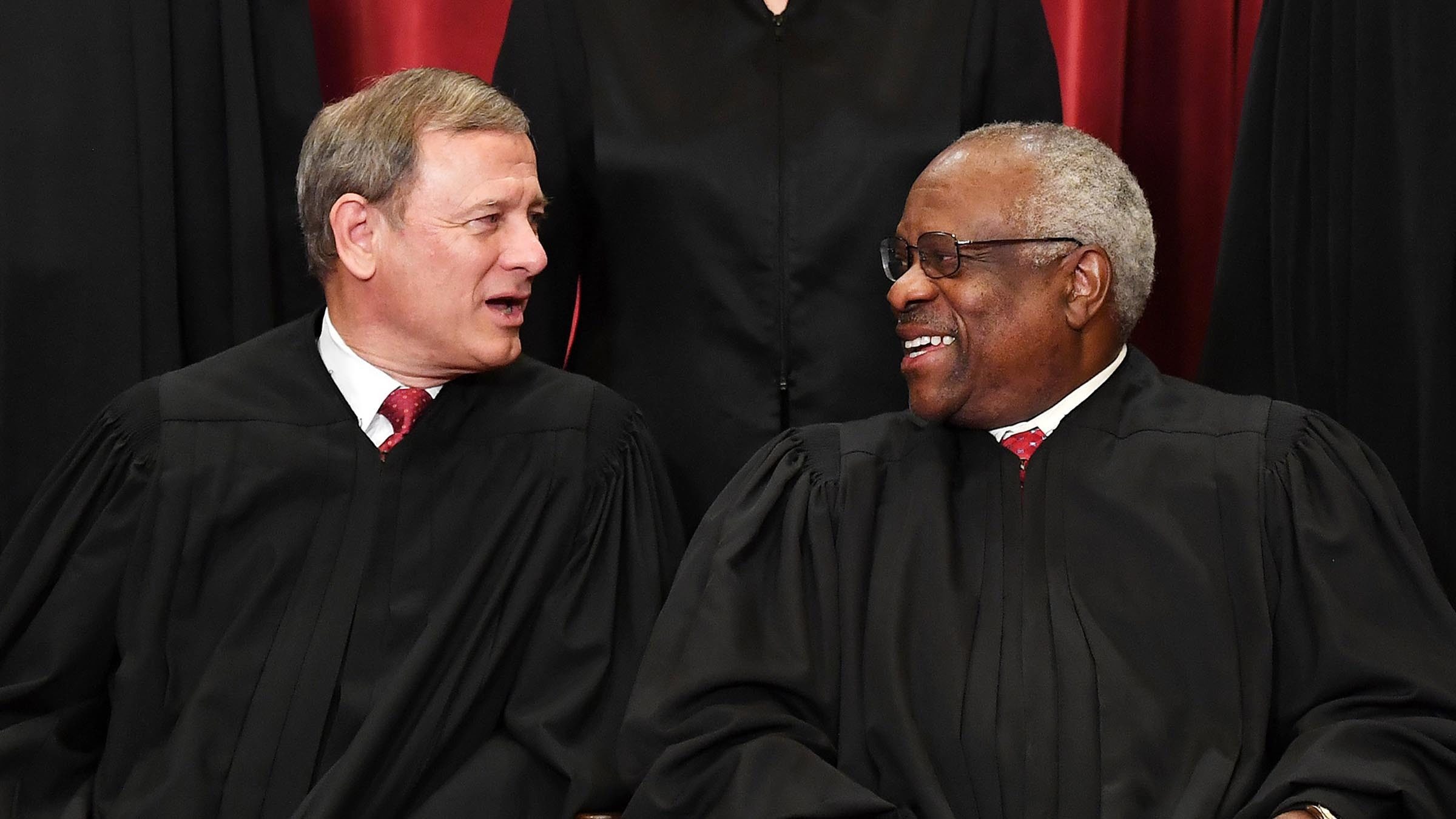

One popular niche of retrospective reframed the Court’s 6-3 conservative supermajority as a nascent 3-3-3 Court: three liberals and three conservatives, but controlled by a supposedly moderate bloc of three thoughtful institutionalists. Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and Justice Barrett, wrote CNN’s Joan Biskupic, were “putting a check on their more conservative brethren,” working diligently to prevent a sudden lurch to the right.

“We are not in a ‘crisis’ when it comes to the Supreme Court,” wrote legal commentator David Lat on June 24, rolling his eyes at the purported urgency of enacting “radical” reforms to the federal judiciary. “The Court is not ‘out of control,’ ‘out of whack,’ a ‘threat to democracy,’ or ‘dangerously out of step with the people.’”

Each of these characterizations proved unequivocally wrong. On July 1, the term’s final day, the six Republican appointees took a jurisprudential buzzsaw to what remains of the Voting Rights Act in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee. By making future challenges to voter suppression laws almost impossible to prove, Brnovich greenlights a tidal wave of anti-democratic bills winding its way through state houses even as you read this sentence. That legislation is championed, of course, by Republicans who have gleefully embraced the Big Lie about the 2020 election and are thrilled to have the chance to meddle in the next one. The opinion in Brnovich is a bizarre, convoluted mess that more or less ignores the law it claims to interpret. In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan castigated the majority opinion as a “law-free zone” laced with occasional “random statutory words” for effect. Her outrage is righteous and satisfying; because it earned only three votes, it is also basically irrelevant.

Mere minutes later, the Court released another 6-3 opinion in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, this time striking down a California law requiring that charities disclose the identities of their largest benefactors. The new standard embraced by the—surprise!—six-conservative majority will make challenges to campaign finance disclosure laws much easier to win, enabling even more of the kajillionaire political spending blessed by the Court a decade ago in Citizens United to take place without the public finding out about it.

And in September, the Court capped off a streak of sweeping, extremist shadow docket decisions by blessing a dystopian Texas law that outlaws abortions after six weeks, cynically evading the guardrails of judicial review by deputizing private citizens as amateur bounty hunters to enforce it. The 5-4 decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson didn’t technically overrule Roe v. Wade. But by allowing a functional ban that openly flouts Roe to take effect in the nation’s second-largest state, the justices quietly accomplished the same result.

The Court, as it has always done, released many of its most consequential opinions in the term’s final days—and as it’s often done recently, it saved some of its dirtiest work for the shadow docket. And for all the fawning media attention paid to occasional displays of unanimity and intermittent deviations from conservative orthodoxy, Roberts and company, as they always do, fell in line on the issues that matter most to the future of the Republican Party and the conservative legal movement.

Even still, many outlets could not disabuse themselves of the notion of a far-right Court improbably tacking to the center. “So much for a rock-solid 6-3 conservative Supreme Court majority,” wrote Bloomberg’s Kimberly Robinson on July 6. In The New York Review of Books, ACLU legal director David Cole proclaimed that the “doomsayers were wrong” about the Barrett Court, “with the notable exception of a disturbingly partisan voting rights decision on the last day of the term.” This is roughly analogous to declaring the Titanic’s maiden voyage a rousing success, but for an unfortunate nighttime incident involving low visibility and an iceberg.

This is hardly the first time commentators bent over backwards to grade the conservatives on the most generous imaginable curve. Last year, after a sharply-divided Court pulled off a flurry of almost comically antidemocratic stunts in order to make it harder for people to vote during a deadly pandemic, commentators heaped effusive praise on Roberts for his steady, virtuous leadership. Amidst the partisan rancor in Washington, rhapsodized The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Rosen, “Roberts worked to ensure that the Supreme Court can be embraced by citizens of different perspectives as a neutral arbiter, guided by law rather than politics.” In a city full of politicians with savvy PR operations, no one has a better team than Roberts.

You can blame these spates of shoddy coverage, at least in part, on the constraints of a fragile media industry and the 24-hour news cycle. It takes more work—more time, more planning, more research—to put a decision like Brnovich in the context of the conservatives’ decades-long war on voting rights than it does to, say, crank out a 500-word opinion recap on the morning of its release. Even for plugged-in reporters, there is precious little time or incentive to do more than read a case like Brnovich, summarize the majority and dissenting opinions, and tally up the votes for each. Plus, journalists also have to worry about preserving the access to practitioners, legislative staffers, judicial clerks, and even the justices themselves on which their reporting depends. (Good luck landing a six-figure advance to write a gossipy The Nine-style bestseller when half the justices won’t talk to you!)

A conservative supermajority doing standard-issue conservative supermajority things also poses something of an existential crisis for the legal commentary industrial complex. The persistent refrain that justices “do law, not politics” is very useful to people who are paid to divine the complex inner workings of a famously opaque institution, explaining to a lay audience what makes the Court’s work special and different. For these writers, it’s far more interesting to hypothesize about the surprising formation of a moderate bloc than it is to dutifully report that the conservatives once again dunked all over the liberals and then laughed in their faces about it. The same impulse that drove journalists to crank out some version of a “Trump Softens Rhetoric, Becoming Presidential at Last?” story every time he coughed up a complete sentence makes “John Roberts, Our Centrist King” a perennially appealing narrative whenever he happens to land somewhere to Sam Alito’s left.

The demographics of the tiny, clubby, insular Supreme Court press corps matter, too. Only two dozen journalists and three courtroom artists hold the coveted “hard pass” credentials that entitle them to full-time access to the Court, making this an especially difficult beat for reporters unconnected to legacy media outlets to break in to. Diversity among Supreme Court reporters also tracks diversity in journalism more generally, which I do not mean as a compliment. As professors and Strict Scrutiny co-hosts Leah Litman, Melissa Murray, and Kate Shaw noted in a recent paper, the five dedicated Supreme Court correspondents working at the country’s top-circulating newspapers are all white guys; many of them have been on the beat for decades. When the worst things the Court does won’t materially affect the lives or livelihoods of the highest-profile people writing about it, the true extent of the harm caused simply isn’t a priority for the column’s final edit.

The Washington press corps’s commitment to both-sidesing every story has long been among the planet’s most promising sources of renewable energy, and legal coverage is no exception. But there is a veritable ocean of room between, say, straight-news reporters calling Brett Kavanaugh a partisan hack on the one hand, and doing credulous stenography for conservative delusions of “judicial minimalism” on the other.

Journalists are forever staring at the institution like a bad magic eye drawing, searching for the moderation they fervently believe will emerge if only they look hard enough.

It is not an opinion, for example, that the six justices who decided Brnovich were appointed by Republican presidents, or that the result helps their political party of choice. It is not an opinion that since the Court decided Roe in 1973, a commitment to anti-choice politics has been table stakes for Republican judicial hopefuls, or that Roe’s shadow-docket disintegration comes on the heels of President Trump’s explicit promises to nominate justices who would vote to destroy the right to abortion care. And it is not an opinion that the rapid-fire confirmations of three dyed-in-the-wool ideologues in four years has cemented a right-wing Supreme Court majority for at least a generation to come.

If the upshot of all this were a regular run of uncritical term recaps, fine. But the unwillingness or inability to engage with the Court as it is, instead of what pundits imagine it to be, quietly carries water for a conservative legal movement that depends for its success on public acceptance of the fantasy of the objective, apolitical judiciary. This myopic focus on process over substance has serious consequences for how people understand and evaluate what the country’s nine most powerful lawyers are doing. In less than two decades, the Roberts Court has merrily set about the task of reshaping American life as it sees fit, eviscerating the power of labor unions, ushering in a new era in First Amendment law of quasi-official Christian supremacy, and reducing your right to vote to a pile of smoldering rubble. If your exposure to media coverage of the Court were limited to a quick scan of these headlines, though, you’d think the justices were getting along famously, and would have no reason to believe anything is amiss.

Weaving at least a cursory discussion of these dynamics into coverage of the Court is not “bias.” It is essential context for understanding what the Court is doing, how it got to this point, and where it is headed next. For too many journalists, however, the mortal fear of getting smeared, ignored, or dismissed for stating unflattering facts about the Court has cowed them into saying nothing meaningful about the Court at all. Instead, they are forever staring at the institution like a bad magic eye drawing, searching for the moderation they fervently believe will emerge if only they look hard enough.