Typically, discussions of qualified immunity arise in the context of letting police get away with literal murder because there isn’t a case precisely on point that tells police that they can’t do that exact sort of murder. Often overlooked in these conversations, however, is the fact that qualified immunity applies to plenty of government officials who aren’t police officers, and who are still free to violate your civil rights more or less with impunity.

A quick qualified immunity refresher: Qualified immunity is a defense available when someone brings a civil suit under a federal law known as Section 1983, which allows people to recover for civil rights violations committed by government officials “under color of law.” But suing under Section 1983 doesn’t mean succeeding under Section 1983. According to the Supreme Court, which created the modern version of qualified immunity some four decades ago, Section 1983 protects officials from civil damages “insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.” Put differently, there isn’t already a case that says that officials can’t do a specifically defined bad thing, they can’t possibly be held responsible for doing that bad thing.

This brings us to schools, where federal courts are often called upon to grapple with situations in which teachers or administrators mistreat schoolchildren in some horrible way. Yet school officials seem to be granted a sort of eternal sunshine of the spotless mind hall pass in which things the rest of us know as objectively unreasonable are just fine. Just as police can’t be bothered, for example, to realize it’s not okay to arrest people for making a parody Facebook page about them because there was never a case before that said they couldn’t, school officials can’t possibly understand it violates the Fourth Amendment to, for example, strip-search a 13-year-old because they believe she might have some highly dangerous substances: prescription-strength ibuprofen and over-the-counter naproxen.

In the aforementioned case, Safford Unified School Dist. No. 1 v. Redding, the Supreme Court did not cover itself in glory with its explanation of why strip-searching teenagers is not that bad: “Because there were no reasons to suspect the drugs presented a danger or were concealed in her underwear, we hold that the search did violate the Constitution,” wrote Justice David Souter for the majority. “But because there is reason to question the clarity with which the right was established, the official who ordered the unconstitutional search is entitled to qualified immunity from liability.” Translation: It’s unconstitutional, but a school official couldn’t have been 100 percent sure that strip-searching a teenager because you suspect they have the good stuff (800mg ibuprofen) is unconstitutional.

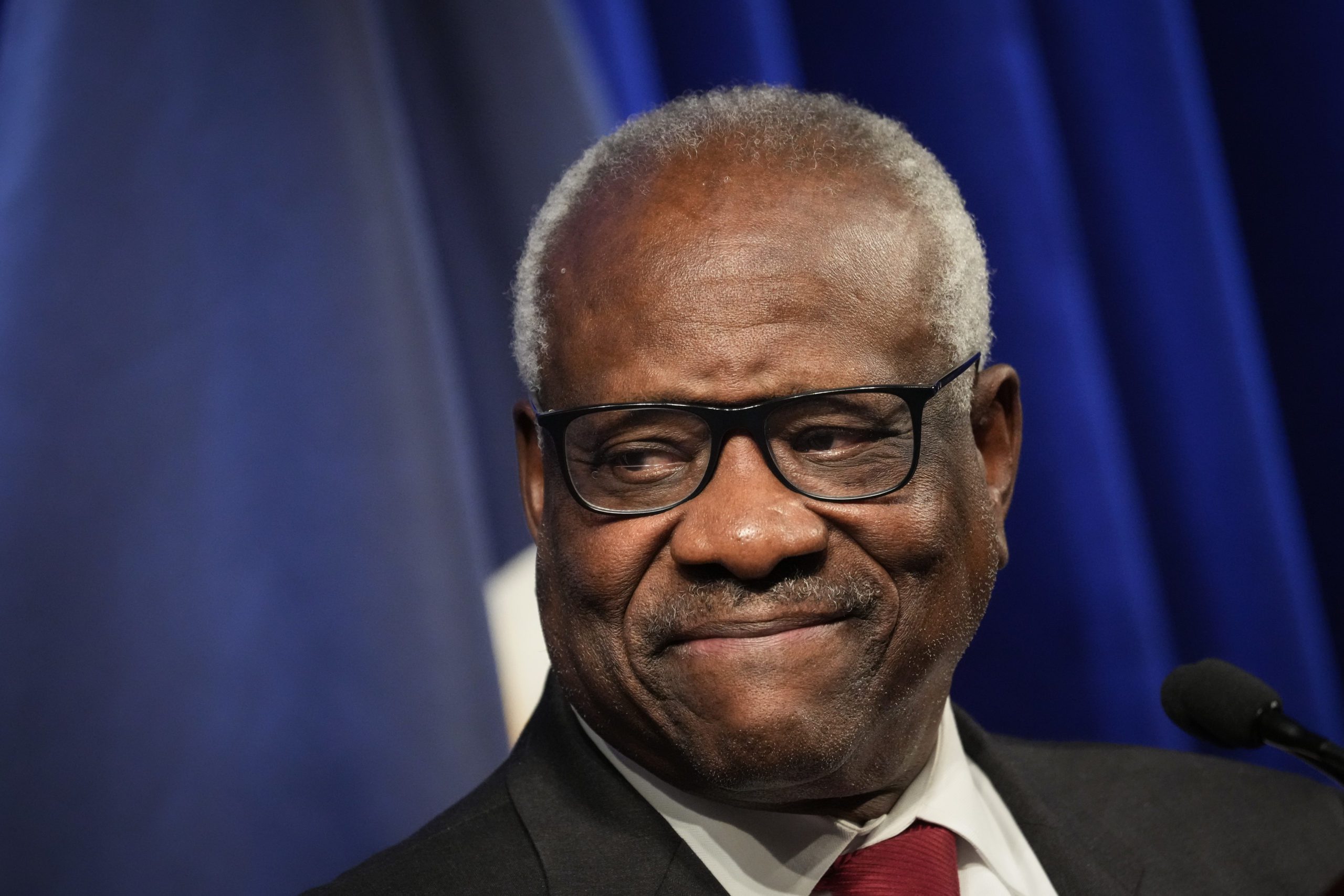

It will surprise no one to learn that Justice Clarence Thomas found even this holding, which still shielded school officials from responsibility, a bridge too far. He wrote separately to complain that the majority, by saying the search was unreasonable, had “surrendered control of the American public school system to public school students.”

In the 13 years since Safford, things haven’t gotten better for students. Multiple federal appeals courts have granted qualified immunity in situations where it seems nigh-impossible for a hypothetical reasonable person to conclude that the behavior of the school officials was unobjectionable. Many of these cases involve special-needs students, essentially giving school officials a pass when dealing with vulnerable minors.

When you see a child losing their constitutional rights (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Last year, in T.O. v. Fort Bend Independent School District, a three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit upheld a lower court’s dismissal of a parent’s action against the school district on behalf of their then-first-grader T.O., who has both Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder. T.O. had been escorted from the classroom due to behavioral issues consistent with his diagnoses. A teacher, Angela Abbott, arrived, and T.O. pushed at her, trying to get back into the classroom. Although T.O,’s behavioral aide told Abbott the situation was “okay,” Abbott, a 260-pound full-grown adult, proceeded to throw a 55-pound first grader to the floor, seize him by the throat, and choke him for several minutes until he foamed at the mouth, all the while yelling that T.O. “had hit the wrong one.”

The Fifth Circuit, however, ruled that T.O. could not pursue a Fourth Amendment cause of action. After characterizing a lengthy choking of a small child as “the momentary use of force by a teacher against a student,” the panel threw up their hands, saying they’d never previously conclusively determined whether such an action was a seizure under the Fourth Amendment. Thus, Abbott gets a pass. The Supreme Court declined to review this case last month.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals made a similar ruling last month in R.A. v. Johnson. There, G.A. had the misfortune to have one Robin Johnson, the defendant, for both first and second grade. G.A. has limited communication functionality as part of his autism spectrum disorder. When he was in first grade, Johnson literally put him in a trash can, telling him that “if he acted like trash, [she] would treat him like trash.” (Another employee reported Johnson to school administrators, who took no meaningful action.) When he was in second grade, the complaint alleges, Johnson spilled hot grease from her lunch on his head and put her hands over his mouth so he couldn’t disturb other students. Another parent reported similar experiences in Johnson’s classroom and talked with a therapist, who filed a police report. Johnson was placed on leave and then pleaded guilty to assaulting a disabled person.

The Fourth Circuit, however, declined to hold the school officials accountable. To do so, the Fourth Circuit engaged in some neat sophistry, pointing out that the plaintiff, R.A.—G.A.’s mother—didn’t specifically use the word “malice” when describing the horrifying things done to her son. There’s also a peculiar discussion of intent: If school officials didn’t intend for Johnson to functionally torture a special needs child, they can’t possibly be in trouble for it. “Given the intense community interest in public education, some of the decisions administrators make will provoke disagreement. Other such decisions may even be ill-advised,” the three-judge panel wrote. “IIf such judgments were often the prelude to litigation, however, the school environment would be transformed.”

(Well, yes. It absolutely would be transformed, ideally into a place where throwing hot grease on children, stuffing them in garbage cans, and choking them would be forbidden.)

When it comes to children in schools, grants of qualified immunity are more akin to grants of qualified immunity to prison officials, where cases often turn on the humiliation of incarcerated people behind closed doors. In 2018, for example, the Supreme Court declined to review a case in which corrections officers threw a prisoner into solitary confinement for a year for having the temerity to ask about commissary access.

Cases like T.O.’s and G.A.’s are not like high-profile extensions of qualified immunity to cops who make split-second decisions to shoot someone while the cameras roll. Instead, the misconduct of teachers and administrators can be long, drawn-out affairs of petty cruelty that never make headlines. Courts are too often willing to decide that holding them accountable is not worth the trouble.