Two weeks ago, I took the bar exam. And after dedicating myself full-time for two months to studying the rules of intestacy and the elements of a fee simple subject to condition subsequent and the requirements of a merchant firm offer, I really learned only one lesson from it all: The bar exam is a blight on the legal profession, and must be abolished.

I don’t yet know if I passed; in my jurisdiction, we don’t get exam results back until November. But it’s a standardized test, and I check a lot of boxes that indicate that my chances of success are good: I’m a white dude. English is my first language. I don’t have learning disabilities or test-taking anxiety. I got a free bar course through a program at my law school. I have a wife who works, enabling me do test prep full-time.

The problem is that precisely zero of these characteristics have anything at all to do with how good of a lawyer I’m going to be. And that is what’s so supremely fucked about the bar exam: It is a barrier to entry to the legal profession that has nothing to do with the requirements of the legal profession, and everything to do with excluding the people whom the profession would most benefit from welcoming.

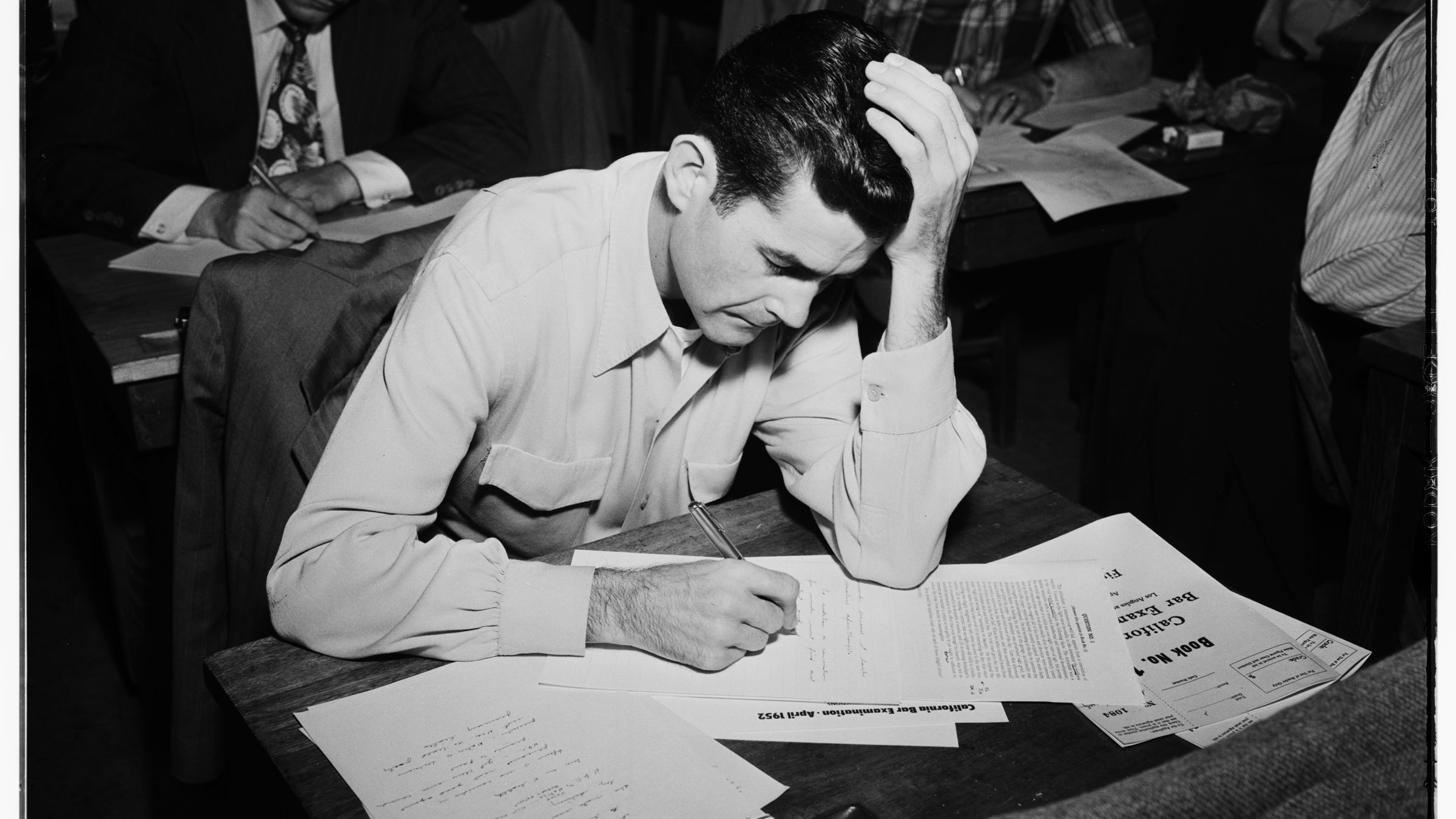

When there are 30 minutes left in the exam and you get another goddamn Rule Against Perpetuities question (Photo by Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images)

For example, my friend Leonela Felix sat about three rows behind me in the test room. This was her third attempt to pass the bar and become an attorney; three more failures and she’s blocked for life.

Leonela is also one of the most committed and effective advocates I know. She’s a state legislator, who in her first term engineered the passage of several important criminal justice reform bills, including the first policy in the entire country providing for automatic expungement of marijuana convictions. She won these important victories, in part, by talking openly about her background as an immigrant Latina who experienced incarceration herself growing up—exactly the kinds of underrepresented life experiences that the American Bar Association (ABA) claims to want more of in the ranks of the legal profession.

Leonela’s boss in her day job, which is also in public service, wants to promote her to a litigation position. But he can’t until she passes this test. Think about that: The public official who works with Leonela every day, who will be held accountable for her results, who has the most to lose by hiring an incompetent lawyer, wants to hire her as an attorney. But because she (by her own admission) struggles at test-taking, isn’t great at speed-reading in her second language of English, and previously couldn’t afford to miss work to study full-time, she’s prohibited from doing the job. So this summer, she was once again forced to invest an ungodly amount of time and resources—two full months off work, and a dip into her limited savings for a bar tutoring class—to try to jump through this hoop.

The bar has three sections: the Multistate Performance Test (MPT), the Multistate Essay Examination (MEE), and the multiple-choice Multistate Bar Examination (MBE). Together, the MEE and the MBE comprise 80 percent of the test and cover well over a dozen subjects: civil procedure, constitutional law, contracts, criminal law and procedure, evidence, real property, torts, corporations, family law, secured transactions, trusts and future interests, and so on. The test format requires examinees to learn each and every statement of law across all of these areas. This year, it featured multiple questions about the notoriously convoluted Rule Against Perpetuities, a 17th-cenutry relic of English common law that requires future interests to vest, if at all, within 21 years after the death of a life in being at the time that the interest is created. Most states have gotten rid of it, because seriously, what does any of that even mean?

This sweeping generalist approach does not remotely resemble the actual practice of law. Although I understand the argument that lawyers should have a basic grasp of a few key subjects, most attorneys will only engage with a fraction of these topics over the course of their careers. I can say with complete certainty that as a climate lawyer, I’m never going to need to know how to perfect a purchase-money security interest in inventory or recite the elements of the implied warranty of merchantability. Indeed, if I were ever asked about such issues, it would be irresponsible of me to provide legal advice. The appropriate thing to do in that situation would be to refer the questioner to someone who actually practices that kind of law.

Like most standardized tests, the exam is also less concerned with testing useful legal knowledge than gauging one’s ability to take a standardized test. The multiple-choice portion is written to trick you, often requiring examinees to choose the least wrong option from a list of slightly wrong answers. The entire exam disproportionately centers obscure laws, arcane exceptions to rules, and (of course) the exceptions to the exceptions to said rules.

As a result, studying for the bar is not about developing a real competency in the law. It’s about memorizing hundreds and hundreds of esoteric rule statements that have almost no relevance to contemporary real-world situations. That’s why you so often hear bar takers say they immediately forgot everything they learned for the exam—because when you shove all this worthless information into your brain for a test, it flies right out afterwards.

Lawyers-to-be awaiting their swearing-in ceremony to the Pennsylvania bar in 2016, several months after passing an exam they absolutely should not have had to bother with (Photo By Ben Hasty/MediaNews Group/Reading Eagle via Getty Images)

Of the three exam parts, only the MPT, which consists of two 90-minute problems in which you process a set of documents and synthesize that information in a mock memo or brief, tests skills that are at all connected to the work of a practicing attorney. Unfortunately, this section only counts for 20 percent of the score in most jurisdictions. To the extent that an aspect of the bar exam could be characterized as relevant, the test treats it as an afterthought.

What’s more, this format actively encourages bad lawyering. The MEE consists of six essays in three hours, and the MBE features 200 questions in six hours, so examinees have 30 minutes per essay and 1.8 minutes per multiple choice problem. And, of course, there are no notes—everything’s off the top of your head. What the bar exam tests, in other words, is your ability to make split-second decisions without consulting legal authorities, which is the kind of behavior that gets actual attorneys sanctioned or worse.

The main argument made by defenders of the bar exam is that it’s necessary to protect the public from bad lawyers. “Those charged with the important responsibility of regulating the legal profession understand [that] public protection remains a priority even in this time of crisis,” wrote the National Conference of Bar Examiners, in an April 2020 report written to discourage states from abandoning the bar exam during the COVID-19 pandemic. “The public, and certainly legal employers, rely on passage of the bar examination as a reliable indicator of whether graduates are ready to begin practice.”

But this is a testable claim, and it turns out to be, empirically speaking, absolute horseshit. Wisconsin is the only diploma privilege state, meaning that law school graduates there are eligible to seek admission to the state bar without sitting for the exam. According to bar defenders’ logic, then, Wisconsin’s legal community should be overrun with idiots and hucksters. But a national ABA survey on lawyer discipline systems found that attorneys in Wisconsin receive about the same number of complaints per lawyer as states with bar exams. Indeed, according to the survey, Wisconsin’s 21,000 attorneys received 1,660 complaints in 2018. Louisiana’s 22,377 attorneys received 2,528.

Pictured: A big ol’ racket (Photo by AaronP/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images)

So why does the bar still exist? One inevitable answer is money, because a lot of people have become very wealthy off this institution. Dozens of bar prep companies with courses costing thousands of dollars feed like parasites on the system, while CEOs like Mike Sims of Barbri have a vested interest in its maintenance. The NCBE, which produces the bar exam, enjoyed a net income of over $17 million in 2020 and owns over $150 million in assets, many of which are located at NCBE’s headquarters in…Wisconsin, the diploma privilege state. In fact, NCBE President Judith Gunderson—the person who’s literally in charge of the bar exam—never actually sat for the bar exam. She became a licensed attorney through diploma privilege, and now pulls in more than $300,000 per year to lobby against it.

Ultimately, though, I think the bar still exists for the same reason that hazing customs at shitty fraternities still exist: Exclusive associations find ritual humiliation to be a useful gatekeeping institution. And if the ritual serves to exclude immigrants, working-class folks, disabled people and other groups who traditionally haven’t belonged in the club, well, so much the better. This kind of gatekeeping has a sordid history in the legal profession. As Oday Yousif Jr. noted in a 2020 op-ed, “The American Bar Association itself was once a White male-only fraternity that voted to only admit ‘worthy members’ in an effort, as its membership chairman said, to keep ‘pure the Anglo-Saxon race.’” The exam has been a key part of this tradition, and although the explicit nature of this racist design has changed, the discriminatory effects remain the same.

I’m usually pretty wary of complaints that center the problems of lawyers, because we are the least significant victims of the oppressive ways in which our legal system operates. But one of the reasons courts are so oppressive is that they’re disproportionately populated by attorneys who can afford to treat the law like a game, instead of what it really is: a system of power with real-world consequences for individuals, communities, and the country.

So fuck the bar. The legal profession isn’t a frat, and it doesn’t need a complex hazing ritual. When people like Leonela, who understand the law’s asymmetries because they’ve actually lived them, are systematically prevented from joining the legal profession, the entire system suffers.