For people who write about the Supreme Court, a well-established shorthand exists for describing who the justices are and how they do their jobs: “conservatives” and “liberals.” This language reinforces a core tenet of American legal culture: Judges—officers of the court who have taken an oath to administer justice faithfully and impartially—are not politicians. Whenever partisan affiliation does come up in a story, reporters are careful to attribute it not to judges, but to the elected officials who nominated and confirmed them.

Consider coverage of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that overturned Roe v. Wade earlier this year. “CONSERVATIVE JUSTICES SEIZED THE MOMENT AND DELIVERED THE OPINION THEY’D LONG PROMISED,” read a headline at CNN, which went on to distinguish between the justices in the majority and the “Republican-appointed conservatives who first voted for Roe and then upheld it.” Bloomberg described the Court’s decision as taking place “along ideological lines,” not to be confused with the reactions from elected officials, which came “along party lines.” In the New York Times, this dichotomy was on display in the very same sentence: The end of the right to abortion access vindicated “a decades-long Republican project of installing conservative justices prepared to reject the precedent.”

This convention is not only useless. It’s dishonest. This Court, controlled by a six-justice conservative supermajority, is the most partisan Court in living memory, and its life-tenured members are at the center of Republican political power in America. And for all the attention that occasional defections or scrambled lineups receive, the more important a case is to the GOP’s electoral prospects, the less likely it is that the final vote will include any surprises.

Legal journalists have a powerful self-interest in maintaining the illusion of a distinction between erudite law and bareknuckled politics: If judges appointed by Republican elected officials simply do what Republican elected officials would have done in their shoes, the need for media outlets to hire specialized legal correspondents suddenly feels a lot less pressing. But after a term like last year’s, it is past time for commentators to abandon the constrained vocabulary of “conservatives” and “liberals,” or Republican and Democratic “appointees,” if they’re feeling spicy that day. They should feel free to refer to Supreme Court justices—to all judges, really—as “Republicans” and “Democrats,” too.

This is not semantics. Much of legal media has failed to accurately cover the Court’s long history of serving as a vehicle for reactionary politics, let alone its recent dramatic lurch to the right. One way to better meet the moment is to incorporate this story in regular coverage: to acknowledge the tremendous political power that judges wield, and the tremendous lengths to which parties go to control them as a result. The media has a responsibility to chip away at the credulous notion that lawyers magically shed lifetimes of personal and professional experience the moment they put on black robes. For anyone who aspires to report accurately on how the legal system does and doesn’t work, making a few tweaks to the newsroom style guide doesn’t feel like too much to ask.

A handful of commentators occasionally dabble in this convention already. Last year, New York magazine’s Eric Levitz argued that Chief Justice John Roberts’s high approval rating among Democratic voters establishes him as “the greatest Republican politician of his generation.” (“If you don’t think that Roberts can be fairly described as a politician,” Levitz wrote, “that only confirms the enormity of his achievement.”) In a Los Angeles Times op-ed recapping recent voting rights cases, UC Berkeley School of Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky identified a simple throughline: “The Republican justices changed the law to dramatically favor Republicans in the political process.” Shortly after Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation in 2018, I suggested at GQ, tongue only partially in cheek, that his formal title should be “Republican Justice,” given his long history as a zealous party operative whose fierce loyalty was rewarded with multiple lifetime appointments to the bench.

Maybe the most thorough recent exposition on the subject came from Harvard Law School professor Michael Klarman, who explained his abandonment of the usual vocabulary in an Atlantic op-ed last year. The traditional “liberal” and “conservative” framework, he argued, “obscures the reality that in today’s ultra-polarized environment, the justices’ voting patterns display fairly consistent partisan preferences, not simply political ideologies.” Klarman continued: “Given this pattern, I will refer to them as either ‘Republican justices’ or ‘Democratic justices,’ as that is what they are.”

These deviations, however, are very much the exception to the rule. In just about any outlet that regularly covers the Court, the justices might be “conservative” or “liberal,” but they are neither red nor blue. And for writers who are not Harvard Law School professors, referring to Breyer as a “Democrat” or to Roberts as a “Republican” will earn you a polite note from your editor explaining that characterizing judges as such is Generally Not Done, and give you a choice between the agreed-upon euphemisms instead.

When Wolf Blitzer puts another state in the red column on Election Night (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

That the worldview of a Supreme Court justice at least somewhat aligns with that of the president who appoints them is, of course, not news. But there was an era in the not-so-distant past when the president’s party was not so reliably predictive of a justice’s performance on the bench. Justices Anthony Kennedy, David Souter, and Sandra Day O’Connor cast key votes to protect the right to abortion care, much to the chagrin of the anti-choice Republicans who put them there. The liberal stalwart John Paul Stevens was President Gerald Ford’s only Supreme Court nominee; Harry Blackmun, appointed by President Richard Nixon, wrote the opinion in Roe. Chief Justice Earl Warren, who presided over the only decade-long stretch during which the Court might be described as “progressive,” was tapped by President Dwight Eisenhower, who ruefully called this choice “the biggest damned-fool mistake I ever made.”

Thanks in no small part to these time-honored folktales of judicial independence, the Court has long presented itself as uniquely capable of operating above Washington’s pitched partisan battles. In 2018, when President Donald Trump griped about an “Obama judge” decision he didn’t like, Roberts issued a rare public rebuke, insisting that legal professionals are politically color-blind. “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges,” he huffed. “What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

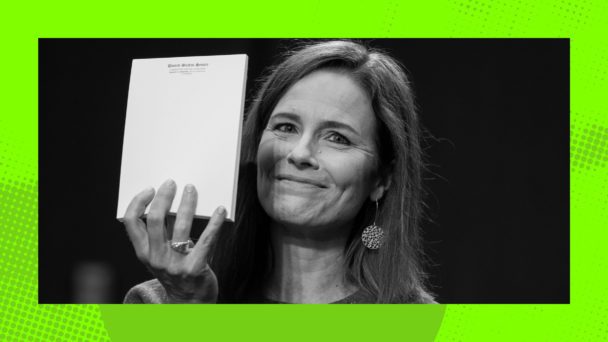

His colleagues frequently echo this language in their public appearances. Judges are not “politicians in robes,” Justice Neil Gorsuch told senators at his confirmation hearings. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote an entire book arguing that justices are not “junior varsity politicians,” and that differences in judicial philosophy are not “political in nature.” In a lecture at the University of Louisville last year, Justice Amy Coney Barrett vowed to try to persuade her audience that the Court is “comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks,” a task that might have been less onerous had she not been introduced by Mitch McConnell in a building with his name on it.

This sentiment is a lie or a delusion, depending on which justice is relaying it. Today, in cases that matter most to the Republican and Democratic agendas, the appointing president’s party is the strongest indicator of how that justice will vote. Last term, of the 19 cases on the merits docket decided by a 6-3 vote, the six conservatives were in the majority in 14 of them—more than 70 percent.

These numbers are especially jarring because the cases do not answer narrow or esoteric legal questions. The substantive issues mirrored those you might hear discussed in a presidential debate: gun safety in Bruen, abortion access in Dobbs, climate change in West Virginia v. EPA. Perhaps a tier down were Kennedy and Carson, a pair of religious freedom cases championed by right-wing activists, and NFIB v. Department of Labor, a test of the federal government’s power to impose a COVID-19 vaccine requirement on large employers. However you’d power-rank these issues in terms of their red-meat interest to Fox News superfans, it doesn’t matter. The conservatives won every single one of them.

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

In no sphere is this trend more dangerous than the law of democracy, where Republican justices reliably rubber-stamp laws that make it easier for billionaires to buy elections and harder for everyone else to vote. The two worst voting rights opinions in recent memory were written by Roberts: Shelby County, which gutted a key enforcement mechanism of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, and Rucho, which declared partisan gerrymandering beyond the ken of federal courts in 2019. A host of GOP-controlled state legislatures passed shiny new voter suppression bills after Shelby County, in some cases unveiling them mere hours after the opinion’s release. For all his highfalutin talk of judicial independence, if Roberts were formally affiliated with the Republican Party, I have no idea what he’d be doing differently.

In a perennially gridlocked Washington, politicians hoping to accomplish anything of substance face tremendous pressure to appoint judges who share their policy preferences and can be trusted to implement them by judicial fiat. This is true for Democrats, too, but Republicans, whose presidents filled 16 of the previous 21 Supreme Court vacancies, have perfected the vetting process. Thanks to the Federalist Society’s emergence as the GOP’s quasi-official judicial selection arm, rock-solid partisan bona fides are table stakes for any conservative lawyer who aspires to take the bench.

The hollow nature of the “judges aren’t partisans” line is evident from the fact that for the right, any deviation from the party line is treated as an unconscionable act of cowardice. “No more Souters” became a rallying cry for Federalist Society types in the mid-1990s, who made opposition to abortion rights a non-negotiable trait for future judicial hopefuls. Roberts is regularly condemned by fringe weirdos for not doing exactly what they want, whenever they want it; after he voted not to strike down the Affordable Care Act in 2012, a Tea Party Patriots spokesperson predicted that historians would one day mention the decision in the same breath as Plessy v. Ferguson and Dred Scott v. Sandford. When confronted with results they did not expect and do not like, conservatives do not accept the result as the inevitable byproduct of judicial independence. They view it as a betrayal.

The insistence on uncompromising loyalty persists today, even as the conservative wing’s stranglehold on power means that Republicans do not have to compromise anymore. In 2020, when Gorsuch wrote an opinion that extended the protections of federal antidiscrimination law to LGBTQ employees, Missouri Senator and noted coup enthusiast Josh Hawley mournfully declared it “the end of the conservative legal movement.” That same year, when Roberts joined the liberals to invalidate an anti-choice law in Louisiana, then-Vice President Mike Pence publicly labeled Roberts a “disappointment.” In the Schoolhouse Rock-esque mythology that surrounds the Court, the legacies of Souter and Kennedy and O’Connor serve as putative proof of the Court’s independence. In practice, the Republican Party has ensured that people like them will never become judges again.

(Photo by Aaron P. Bernstein/Getty Images)

As bad as the Court’s 2021-22 term was for everyone to the left of, say, Kyrsten Sinema, what the Court does next will not be better. In the months to come, the justices will have the chance to relieve Republican state legislators of the burdens of having to draw fair electoral maps or honor election results. They will consider facial challenges to the use of affirmative action in higher education admissions, and to laws that protect what little remains of Tribal sovereignty. They will decide if antidiscrimination laws apply to everyone, or if the government is powerless to outlaw bigotry in public accommodations when a bigot claims that compliance would impose on their creative process.

Again, these are not abstract or technical questions. They are policy decisions of profound importance to everyone living in this country, rephrased in legalese and packaged as anodyne disputes between a particular petitioner and a particular respondent. If Congress were considering a bill on one of these subjects, journalists would obviously note the partisan affiliations of its supporters and opponents. By failing to do so when it comes to the Court, journalists obfuscate responsibility for the consequences of its decisions, whitewashing subjective policy choices as the objective products of an apolitical legal process.

Already, there are signs that the public is developing a sharper understanding of how the Court works than many of the people who cover it for a living. An August Pew survey found that 53 percent of Americans think the justices are doing an “only fair” or “poor” job at setting aside their political views—a five-point increase since January. Part of the reason the justices are twisting themselves into rhetorical knots to persuade the public that they are not political actors is the emerging public consensus that they are full of shit.

Legal journalism that rejects this taboo is better because it is honest: It describes judges as they behave, instead of parroting a narrative promulgated by nine lawyers who have power and want to keep it. The fact that the people who control the Court right now are the same people who would be most upset if references to their partisan affiliation became commonplace is a pretty good sign that journalists shouldn’t shy away from such references any longer.

If a judge looks like a Republican, quacks like a Republican, and enables the rampant suppression of Black voters like a Republican, it’s okay to say that they’re a Republican, whether the designation appears on their nameplate or not.