For six justices put on the Supreme Court to get rid of the right to abortion care, Justice Samuel Alito’s leaked draft opinion that would overrule Roe v. Wade is the culmination of their life’s work. But Dobbs is the beginning, not the end, of this Court’s right-wing counterrevolution. Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case that protects the right of same-sex couples to marry, is next on the conservative justices’ civil rights chopping block.

Alito spends a great deal of his draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization criticizing the Roe opinion for failing to “note the overwhelming consensus of state laws” at the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification, which, he says, does not support the existence of a right to abortion. This claim is, to put it generously, dubious. But at root, Alito is just unhappy that people today have rights that did not exist 150 years ago. He bemoans the notion that the Court would dare to acknowledge that times change, and that rights necessarily expand as a result. If it wasn’t legal in 1868, Alito does not want it to be legal now or ever.

This cramped conception of liberty would fix rights in amber, forevermore preserving the status quo from an era when only men—straight, cisgender men—had rights in the first place. For Alito, the Constitution only protects unenumerated rights that, in Alito’s judgment, are “deeply rooted in our history and tradition,” and “essential to our Nation’s scheme of ordered liberty.” Everything else is left to the political branches to sort out.

That test will permanently exclude women. It will always exclude LGBTQ people, rendering them second-class citizens. To the extent people who aren’t straight white men do enjoy rights, those rights will always be in jeopardy, liable to disappear at any moment depending on the whim of the electorate.

Threaded throughout Alito’s opinion is his disdain for any law that empowers people to have bodily autonomy, to love who they love, and to marry who they want to marry. He’s mad as hell about the opinion in Casey v. Planned Parenthood, which discussed the right to make “intimate and personal choices” that are “central to personal dignity and autonomy.” Although he briefly allows that state legislatures can still pass laws to protect abortion, nothing in Alito’s draft opinion suggests that he hopes they will do so. If he believed that, the opinion wouldn’t be replete with medical misinformation about fetal viability, and blithe assertions that abortion is unnecessary in 2022 because “a woman who puts her newborn up for adoption today has little reason to fear that the baby will not find a suitable home.”

And then comes the inevitable assertion that other landmark decisions that rely on Casey are wrong, too: Lawrence v. Texas, which recognized a right to sexual privacy, and Obergefell. Alito throws in a halfhearted purported distinction between Roe on the one hand, and Lawrence and Obergefell on the other: “Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on our precedents that do not concern abortion,” he says, for abortion is “unique” in that it destroys “potential life.” His explanation does not stand up to even cursory scrutiny. The thesis of Alito’s argument is that when people disagree about rights, the Court shouldn’t get involved. The Republican-controlled states that will inevitably take up this invitation will not limit themselves to abortion.

Alito is also aware that conservative activists are explicitly calling for the Court to use Dobbs to get rid of Obergefell, too. The Thomas More Society, for example, complained that Obergefell “articulated no limiting principle on the basis of which States may prohibit polygamy or incestuous marriages.” The architect of Texas’s SB8, the six-week abortion ban, declared in his brief that “Lawrence and Obergefell, while far less hazardous to human life, are as lawless as Roe.” A group of conservative governors condemned the scourge of “judicial paternalism,” longing for when legislatures could just vote on whether people were equal to one another. The war on the rights that flow from Roe isn’t happening in a vacuum. It’s part of a broader right-wing project to read unenumerated rights out of existence.

The other reason one can presume that Alito wants Obergefell gone: He’s said so himself. In 2020, both he and Justice Clarence Thomas called it an “alteration of the Constitution” that allows “courts and governments to brand religious adherents who believe that marriage is between one man and one woman as bigots.” Alito complained about this in a 2020 speech to the Federalist Society as well, whining that “you can’t say that marriage is the union between one man and one woman” without being accused of bigotry. When Alito won’t stop complaining about Obergefell as wrongly decided, no one should take him at his word that he and the rest of the conservative majority won’t leverage victory in Dobbs into dismantling the rest of the rights they don’t like.

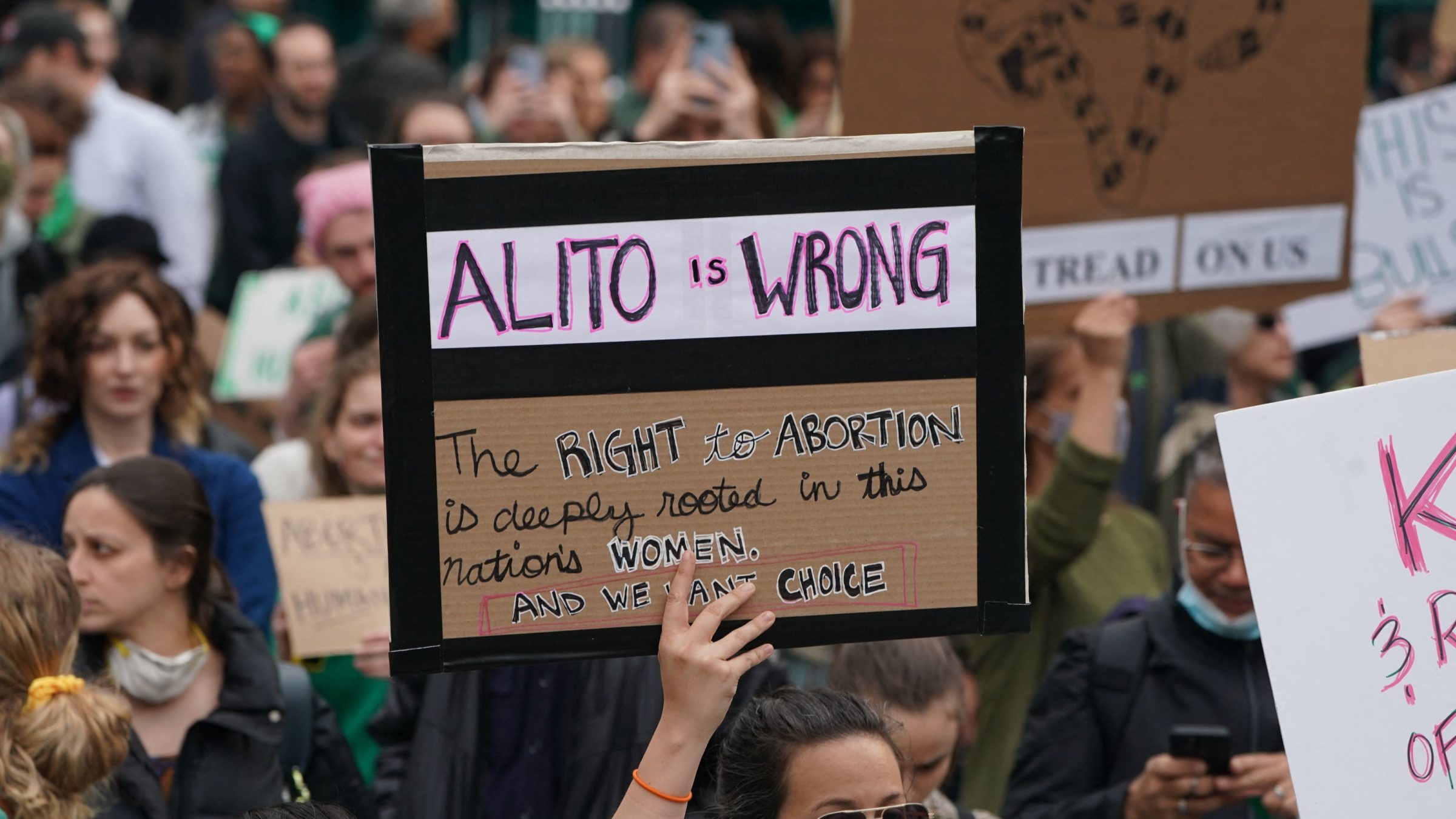

(Photo by BRYAN R. SMITH/AFP via Getty Images)

Alito wraps with a too-cute-by-half bit about how it’s fine and dandy to return abortion rights to the states because “women on both sides of the abortion issue [can] seek to affect the legislative process by influencing public opinion, lobbying legislators, and running for office.” Right now, women compose a whopping 27 percent of the House and 24 percent of the Senate. The numbers are absolutely minuscule for LGBTQ people, 11 of whom serve in the two chambers. The judicial branch is supposed to protect the rights of members of unpopular constituencies whom the political process does not defend. The notion that marginalized people can just run for office to preserve their evaporating rights is equal parts insulting and unhinged.

It’s easy and correct to slam Justice Anthony Kennedy for many things, including the fact that he gave us Justice Brett Kavanaugh. But Kennedy’s 2015 opinion in Obergefell defines the hard work the Court must do. “The identification and protection of fundamental rights is an enduring part of the judicial duty to interpret the Constitution,” he wrote. Since “the nature of injustice is that we may not always see it in our own times,” he continued, the founders “entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.” That’s a beautiful sentiment, truly. It sets the work of the Court: to be ever-active, ever-growing, ever-vigilant in defending those without power from those who have it.

Alito’s opinion, by contrast, is lazy as hell. It would return everything to legislatures for mob-rule popular votes, shifting the Court’s responsibilities to elected officials who may or may not care about them. If you live in a state that hates same-sex couples? Too bad, Alito says, for the Court “cannot bring about the permanent resolution of a rancorous national controversy simply by dictating a settlement and telling people to move on.”

He is wrong. The Court does that all the time. It did it with Brown v. Board of Education. It did it with Loving v. Virginia. It did it with Lawrence, and Obergefell, and a host of other cases that are now on thin constitutional ice. The legal system, for all its myriad flaws, has occasionally managed to endow more people with more rights. The Roberts era will be famous only for unwinding them.