Last week, the Senate confirmed Sunshine Sykes to a federal district court judgeship in the Central District of California, making her the first Native woman to serve as an Article III judge in the state. Prior to her confirmation, Sykes served as a judge in the appeals division of Riverside County Superior Court, where she was the first Native woman to serve in that role, too.

Previously, Sykes worked for Riverside County in juvenile dependency proceedings, and for the Southwest Justice Project as a contract attorney for their juvenile defense panel. As a state court judge, she also trained judges and lawyers across California on the long history of policies that facilitated the state-sanctioned kidnapping of as many as 3 in 10 Native children. (Not until 1978 did Congress take action by passing the Indian Child Welfare Act in an effort to end this family separation crisis.) Sykes will join four other Native women currently serving as federal district court judges: Lauren King in Washington, Diane Humetewa in Arizona, Ada Brown in Texas, and Lydia Kay Griggsby in Maryland.

For most of the federal courts’ 233-year history, indigenous representation among judges was non-existent. In fact, only seven out of more than 4,200 federal judges have identified as American Indian, including Sykes. No Native person has ever served on a federal appeals court or the Supreme Court. There have been more impeached Supreme Court justices—one, more than two centuries ago—than Native justices.

Apart from the four women mentioned above, the two other federal judges to claim indigeneity—and who apparently dispute the title of first Native judge—are Frank Howell Seay and Michael Burrage. Seay didn’t publicly claim indigeneity until 2010, more than 30 years after his confirmation in 1979. In an interview, he shared that when he was in his 50s, his aunt informed him that his paternal great grandfather was “a full-blooded American Indian, probably a Cherokee.” Burrage is an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw nation, and his law firm’s website states he “became the first Native American Federal Judge when he was appointed by President William Jefferson Clinton in 1991.”

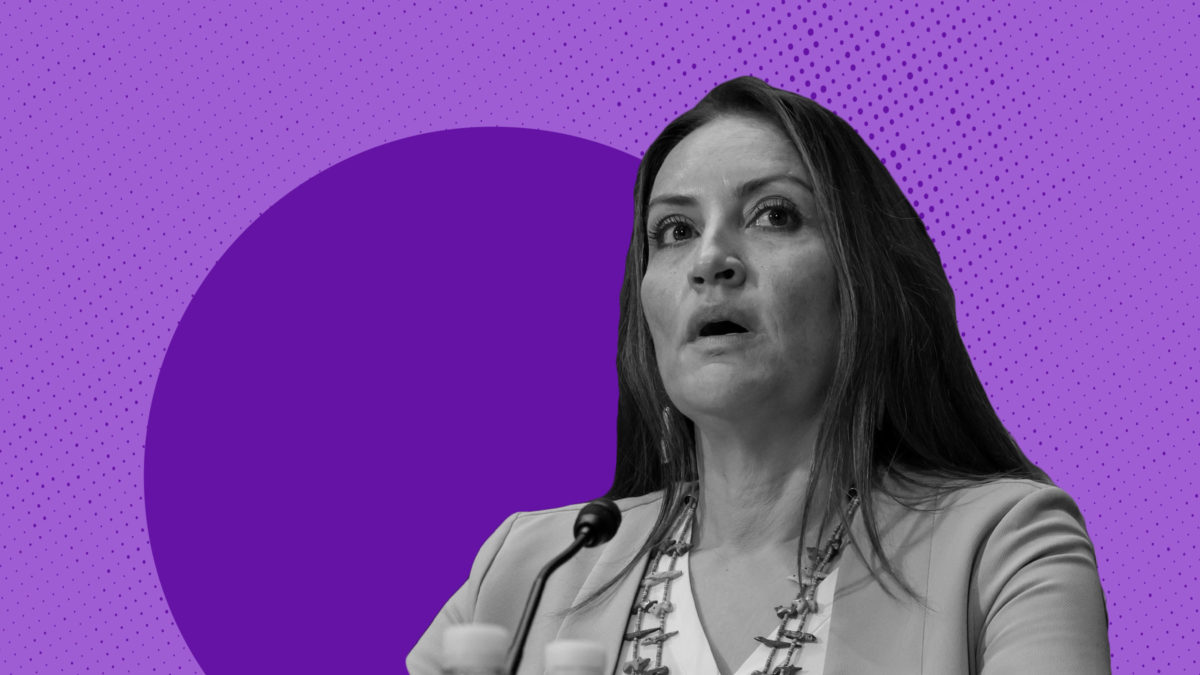

(Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

The lack of Native federal judges is hardly surprising considering that Native representation is lacking throughout the legal profession. In 2020, less than 0.3 percent of admitted law students identified as Native, even though Native people represent 1.6 percent of the U.S. population. Only 12 percent of accredited law schools offer clinics, certificates or programs for students interested in specializing in Indian law; fewer than three dozen enrolled tribal members are tenure-track law school professors.

Judicial clerkships are a key aspect of the law-student-to-judge pipeline, but there, too, Native lawyers are vanishingly rare. According to NALP, only 0.2% of judicial clerkships offered to 2019 law school graduates went to members of indigenous groups. Not until 2018 did Tobi Young, a citizen of the Chocktaw nation, become the first Native Supreme Court clerk, serving for Justice Neil Gorsuch.

The nomination of more indigenous lawyers to the federal judiciary is particularly important in the context of ongoing legal challenges to indigenous sovereignty. Just last month, the justices heard arguments in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, a follow-up case to the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which held that the Muskogee Creek nation was “Indian land” under an 1833 treaty between the U.S. and the Creek Nation. Now, for the purposes of criminal law, over 40 percent of Oklahoma is considered Native land, where state authorities cannot prosecute crimes allegedly committed by indigenous people.

McGirt sent conservatives into a frenzy; Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt, a Republican, recently warned that masses of people would falsely claim indigeneity to avoid criminal prosecution. (“We have people on death row who are doing 23andMe DNA tests trying to get their convictions overturned,” Stitt told Fox New host Tucker Carlson). Yet as Matt Irby explained for Balls and Strikes, the true concern is the potential loss of tax and regulatory power over this wide swath of Oklahoma, since Oklahoma’s pro-industry regulations are in conflict with the tribe’s interests in sustainable preservation of its land. In an effort to weaken McGirt, the state claims in Castro-Huerta that it has jurisdiction over non-Indians who commit crimes on that land against an indigenous person. The Court’s resolution of this case will answer important questions about how far, exactly, the Native sovereignty announced in McGirt actually extends.

The legal attacks on Native rights will continue next term when the justices hear arguments in Brackeen v. Holland, a challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act that conservatives are using as a vehicle to undermine indigenous sovereignty. The Brackeens, a white couple, seek to adopt a toddler who is a citizen of Cherokee nation and of Navajo descent. They are asking the Court to declare the entire law unconstitutional because it racially discriminates against them.

This is hardly an ordinary custody dispute. The Brackeens have the full weight of the Texas Attorney General, and conservative think tanks like the Cato Institute backing their “reverse racism” argument. (They are also represented pro bono by Gibson Dunn, a corporate law firm that, as Native journalist Rebecca Nagle has noted, has a significant number of clients with a vested interest in maintaining Oklahoma’s existing anti-regulatory scheme.)

Nor is this argument new; as the Native journalist Nick Estes points out, white lawmakers in the 1950s made similar “reverse racism” claims in order to privatize dozens of tribal reservations for the benefit of mostly white settlers. Before a friendly audience of justices who have long ignored the difference between race-conscious reparative policies and racial discrimination, the Brackeens and their allies can argue that a law designed to keep indigenous families intact after centuries of state-imposed separation is “reverse racism” in action.

More Native judges won’t make these assaults on indigenous sovereignty go away. But when Native self-determination is under attack, it’s unacceptable to have a federal judiciary composed almost exclusively of people for whom Indian law is little more than an academic exercise.