In South Carolina’s redistricting process, Black voters are shuffled around like a game of three card monte—and democracy always loses.

Historically, the state’s first congressional district has been anchored by the city of Charleston, and has been a Republican stronghold for decades. But in recent years, the GOP’s grip on power there has become less secure. Black people now make up about a quarter of Charleston’s population, and voting pattern analyses show that the district would lean Democratic if it were between 21 and 24 percent Black. At 20 percent, the district would be a toss-up; at 17 percent, the district would lean Republican.

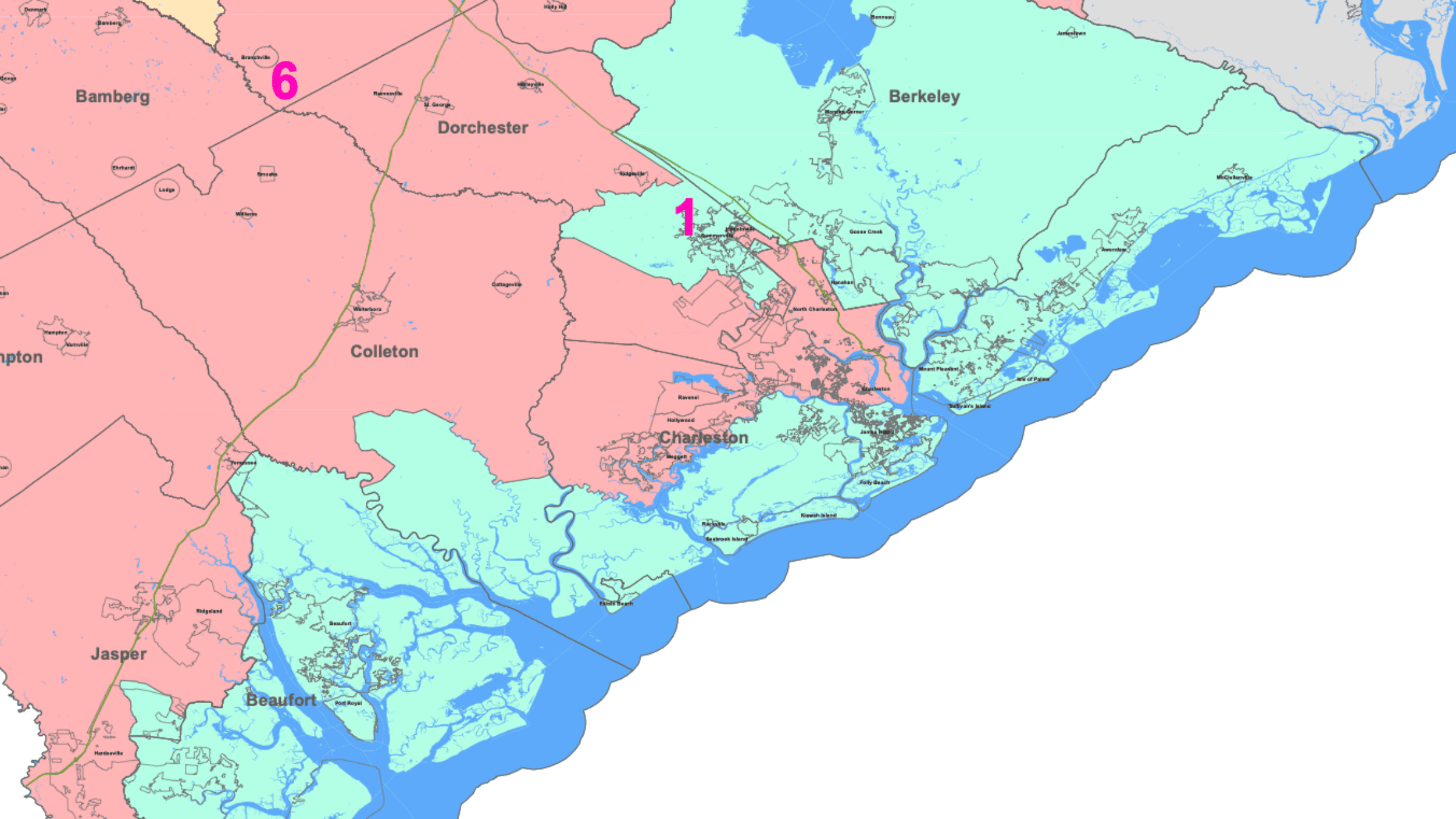

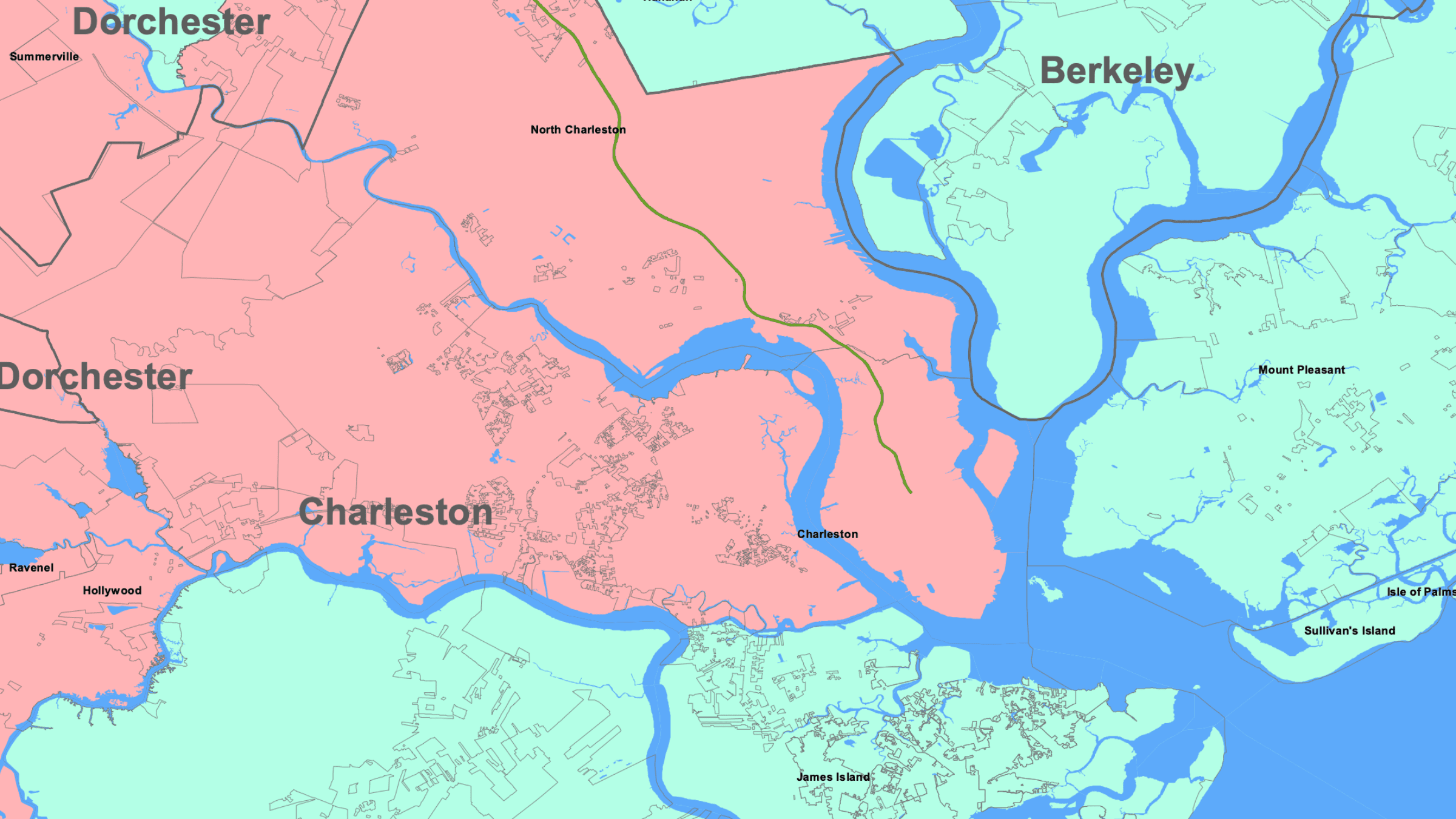

After the 2020 Census, the state’s Republican-led legislature started the process of drawing new maps for the next decade. The final product excised tens of thousands of Black Charlestonians from the district, moving them over to the sixth district. All told, more than 60 percent of Black residents who used to be in District 1 found themselves with new representation in Congress. The new District 1 is not contiguous: unless you’re getting in a boat, you can’t travel from one end to the other without passing through District 6. And wouldn’t you know it, all this cracking and packing brought District 1’s Black population down to 17 percent—the exact number that keeps it safely in Republican hands.

A very normal congressional district (via South Carolina Senate)

In October 2021, the South Carolina chapter of the NAACP challenged this district as an unlawful racial gerrymander. And after an eight-day trial, a three-judge district court panel unanimously ruled for the NAACP, concluding that the legislature’s attempt to bring the district’s Black population “down to the 17% target” was “no easy task,” and “effectively impossible without the gerrymandering of the African American population.”

But the lawmakers contend that the court got it all wrong: They insist that they were drawing lines to maximize the Republican Party’s electoral power, not to minimize Black voters’ electoral power. “Purported racial effects” of the line-drawing process do not “prove a racial target,” they say, since they wouldn’t have used “a (nonexistent) racial target as a proxy for politics” when they “could and did use election data directly for politics.” In other words, according to the legislature, they are just regular partisan hacks, not racist partisan hacks.

Republicans have a strong incentive to claim that their map was driven by party politics alone, because in 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan gerrymandering claims can’t be resolved in federal court. But in the real world, this is mostly a distinction without a difference: Because racial gerrymandering and partisan gerrymandering both harm voters of color, repackaging illegal racial gerrymandering as mere partisan gerrymandering could give gerrymanderers an escape hatch from judicial scrutiny. In Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, the Supreme Court will decide whether states can get away with this racism rebrand.

The lawmakers’ attempt to disclaim the role of race in the redistricting process is a hard sell. The lower court’s opinion made reference to “particularly probative” expert testimony which showed that a precinct’s racial composition was a “stronger predictor of whether it was removed from Congressional District No. 1 than its partisan composition.” In other words, Republicans were likelier to kick you out of the district if you were Black than if you were a Democrat. Further, the legislators’ redistricting counsel testified that the political data used to make the map, which a consultant built based on 2020 election results, was “badly skewed” and “almost worthless.” Racial data, on the other hand, was a more reliable predictor of electoral outcomes since, as the legislature’s own consultant acknowledged, there is “no doubt” that voting in South Carolina is racially polarized and Black voters overwhelmingly support Democratic candidates.

The lawmakers here are nothing if not consistent: Disenfranchising Black voters is a time-honored tradition in South Carolina. A group of historians filed an amicus brief in Alexander discussing how South Carolina has used intimidation, gerrymandering, stuffed ballot boxes, and sometimes murder to prevent Black political participation since the Reconstruction Era. Their brief also points out the “uncanny resemblance” between District 1 and an infamous 1882 racial gerrymander called the “boa constrictor” district.

“A close study of South Carolina’s history, combined with the evidence proffered by Appellees below, leads to the inexorable conclusion that the implemented map at issue was drawn to harm Black voters,” the historians write. “The aphorism that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it is apt here.”

Hope you have a boat!

The legislature and the amici supporting them contest the relevancy of this history and present. The attorneys general of more than a dozen other states argue that past discrimination cannot “condemn” lawful action “in the manner of original sin.” (It’s probably not a coincidence that all the attorneys general are Republicans, and most represent states that were part of the Confederacy.) Other briefs emphasize that the legislature is entitled to a “presumption of good faith.” Good faith, though, is not the same as uncritically accepting what the legislature says without regard for evidence to the contrary. There is no legal obligation to be so open-minded that your brain falls out.

The Republican establishment is hoping that the Supreme Court joins them in blessing racial gerrymandering simply by calling it something else. Doing so would make it harder for voters to challenge discriminatory maps as illegal, and harder still for Black voters to participate in the political process. The question in Alexander is whether the Court’s conservative supermajority will bless racial gerrymandering just because racism got a new PR team.