On Thursday, nearly a month after a deadly shooting in Uvalde, Texas, claimed the lives of nineteen elementary school students and two teachers, the Supreme Court in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen struck down a New York law that requires handgun owners to get a license before carrying it in public.

The New York law at issue in Bruen requires gun owners to show “proper cause” to carry—some “special need for self-protection distinguishable from that of the general community.” The lawsuit was brought by Brandon Koch and Robert Nash, two men whose applications were denied under this standard. A federal district court and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals turned them away, holding the law valid because it furthered the important governmental interest of ensuring public safety.

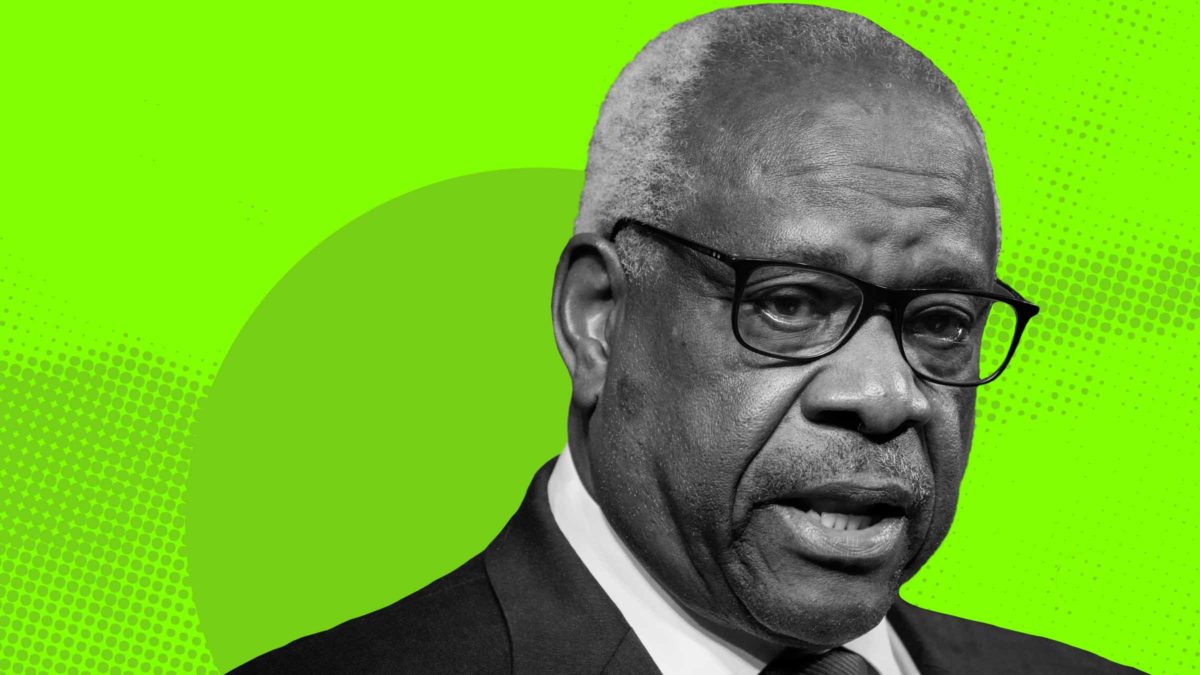

The Supreme Court disagreed. The opinion, written by Justice Clarence Thomas, held that New York’s “proper cause” requirement violates the Second and Fourteenth Amendments because it impedes on a fundamental right to carry firearms for self-defense. Bruen also creates a new test for gun safety laws that will make it even harder for state legislatures to pass gun reform measures: Going forward, the government must prove that a given regulation is “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” If the government cannot point to a centuries-old law that a judge deems sufficiently analogous to a new proposal, the Second Amendment does not allow it.

Whether a type of regulation fits within Thomas’ particular vision of “historical tradition,” it turns out, is answered by whether it supports the outcome that Thomas prefers. His opinion places great weight on anecdotes that, in his view, cast doubt on the legitimacy of gun regulations, and downplays those that indicate otherwise. Evidence of medieval-era traditions of gun regulation, for example, is too old to be relevant; so are colonial-era handgun laws, which “provide no justification for laws restricting the public carry of weapons that are unquestionably in common use today.”

For every bad fact, Thomas has an excuse to wave it away. Similar laws are not similar enough. More recent gun control laws are mere “outliers,” he says, and their “value in discerning the original meaning of the Second Amendment” is “insubstantial.” For this conservative supermajority, the only history that matters is that which allows them to treat the right to bear arms with “unqualified deference.”

Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, calls out the majority’s selective history lesson, and criticizes their approach for giving “judges ample tools to pick their friends out of history’s crowd.” The dissent also captures the frustrating heads-I-win-tails-you-lose logic that permeates Thomas’s opinion: “Some of the laws New York has identified are too old. But others are too recent. Still others did not last long enough. Some applied to too few people. Some were enacted for the wrong reasons,” he writes.

Although Thomas and his fellow conservatives often decry judicial intervention in the policymaking process, the Bruen standard allows the justices to do exactly that. It will burden states attempting to pass regulations to curb gun violence, during a time where the ongoing gun violence crisis is at the height of public concern. It entrusts the inherently subjective task of interpreting history to nine amateur historians, and deems the process objective and the results unassailable.

Critics of originalism often argue that it is a thinly-veiled strategy for conservative judges to arrive at their preferred policy outcomes. The Bruen Court does not even attempt to argue otherwise. This is mask-off originalism: The facts they like carry the day, and the inconvenient facts are banished to the footnotes.