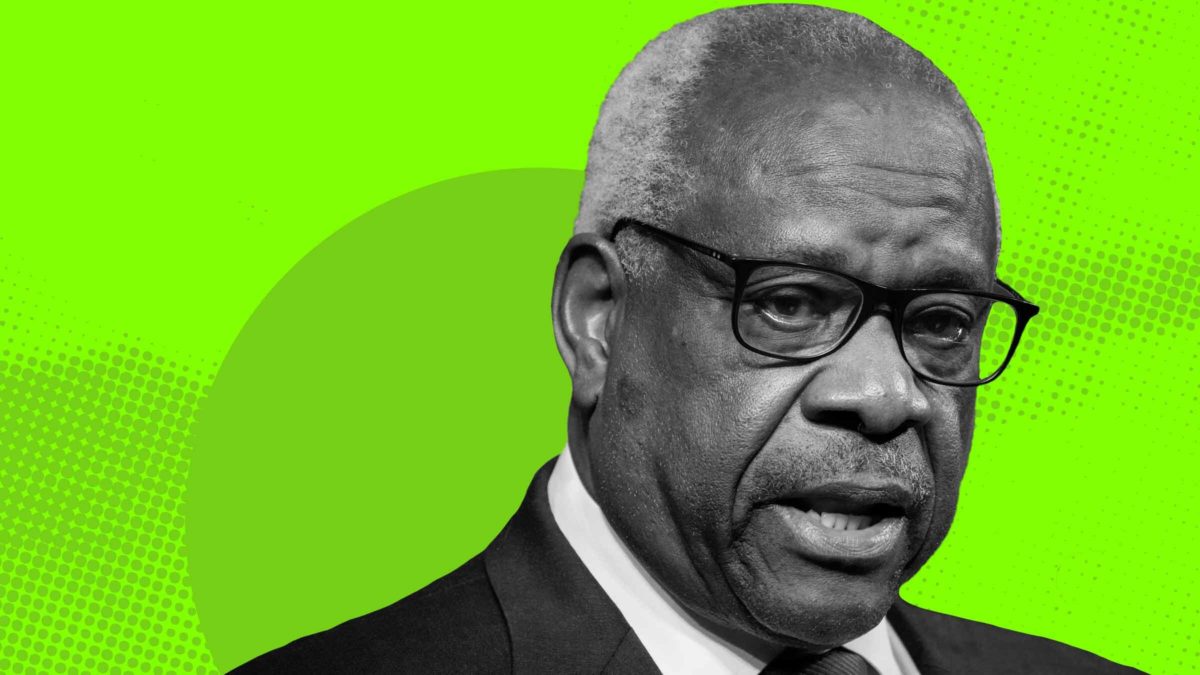

Since 1997, Justice Clarence Thomas has insisted that the Supreme Court has a responsibility to better define the scope of the vaguely-worded Second Amendment, which reads as follows: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” After the Court enshrined a limited right to gun ownership in the home in 2008’s District of Columbia v. Heller, Thomas turned up the volume, lambasting his colleagues for avoiding the issue over the ensuing decade. He has described the right to bear arms as the Court’s “constitutional orphan” relative to other hot-button issues like abortion, speech, and policing, and insisted that the Court should not “impose such a hierarchy by selectively enforcing its preferred rights.” In other words: Gun rights matter too.

Yesterday, the Court heard oral argument in a case that might finally give Thomas his wish: New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, a challenge to a New York state statute that makes it very difficult for residents to obtain a license to carry a concealed handgun in public. As I crudely put it to some friends recently, the Court in Bruen will decide whether the government can prevent you from being strapped outside the crib—and if they can, what are the limits, if any, to that power. After decades of dodging appeals from frustrated gun enthusiasts in blue states, the Court is letting gun rights advocates shoot their shot. As the comedian Red Foxx would say, “I think this is the big one.”

The case has produced a bunch of strange bedfellows that do not follow the usual ideological lines. As America’s gun violence crisis continues unabated, groups of prosecutors, former police chiefs, and former national security officials are joining organizations like the NAACP in urging the Court to preserve these laws in the name of public safety. Meanwhile, a set of affinity-based gun groups like Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership, the Asian Pacific American Gun Owners Association, and yes, Black Guns Matter, argue that the law leaves members of traditionally marginalized communities unable to protect themselves—and dependent on police forces who have proven unwilling or unable to keep them safe.

Whatever you think about who gets the better of this debate, what I contend, beloved, is this: First, Clarence Thomas will be a key figure in how this case shakes out. And second, no matter the result, the outcome will likely be disastrous for Black Americans and members of other minority groups.

Thomas is the Court’s most vociferous Second Amendment defender. By virtue of his seniority—he is the longest-tenured member of the Court—and his well-established views on gun rights, Thomas has a long paper trail on the issue. The advocates in Bruen must contend with his views, most of which are favorable to the law’s challengers.

This case is also an ideological match made in heaven: The Court’s most conservative member has nudged a conservative supermajority to hear a case on an issue near and dear to the conservative legal movement. The two likeliest outcomes are a conservative opinion authored by Thomas that substantially expands the scope of the Second Amendment, with the press corps’ favorite moderate Chief Justice John Roberts joining an irrelevant four-justice dissent, or an opinion not written by Thomas but that unites the conservatives behind something marginally less extreme than his preferred status quo. Either way, notwithstanding his historically quiet demeanor, Clarence Thomas will be very much in the building.

Bruen nicely tees up themes that Thomas has deployed in previous opinions, particularly the racist history of gun control. In McDonald v. Chicago, which the Court decided in 2010, a Black war veteran in his 70s sued after local regulations prevented him from obtaining a gun, even after his home in Chicago was burglarized. In a concurrence, Thomas offered a brief history of slavery-based prohibitions on Black gun ownership and post-Civil War mob violence that prompted Black people to take up arms. A decade later, advocates have adopted Thomas’ focus and added a presentist gloss, pointing to the ways that overcriminalized Black gun ownership fuels racialized mass incarceration. An amicus brief filed in Bruen by a coalition of New York public defenders notes that in 2020, 96 percent of those arrested for gun possession were Black or Latino.

Thomas’s conservative colleagues, too, seem eager to buy this logic in the name of Second Amendment expansion. During oral argument, noted racism skeptic Justice Samuel Alito asked about the anti-Black and anti-Italian origins of New York’s gun law; a “major reason” for its enactment, he suggested, was “the belief that certain disfavored groups…were carrying guns, and they were dangerous people, and they wanted them disarmed.” Alito also complained about the plight of blue-collar New Yorkers—read, minorities—who face gauntlets of armed criminals on late-night train rides but can’t obtain a license to carry themselves. His questions of New York’s solicitor general, Barbara Underwood, sounded like those of a man whose primary experience with the New York City subway system came from watching Grandmaster Flash’s dystopian “The Message”. “There are a lot of armed people on the streets of New York and in the subways late at night right now, aren’t there?” Alito asked. Underwood was baffled. “I don’t know that there are a lot of armed people,” she said.

Justice Alito suggests that New York’s concealed carry restriction was passed with the intent to discriminate against racial minorities, Italians, and members of labor unions. If you are familiar with Alito’s jurisprudence on unions and racism, you will understand the irony here. pic.twitter.com/rz7cMCIew9

— Mark Joseph Stern (@mjs_DC) November 3, 2021

In the past, Thomas has offered inaccurate histories of racism to argue for prohibitions against affirmative action and abortion; imagine what he and/or his colleagues might do with more accurate histories and data about Black gun ownership.

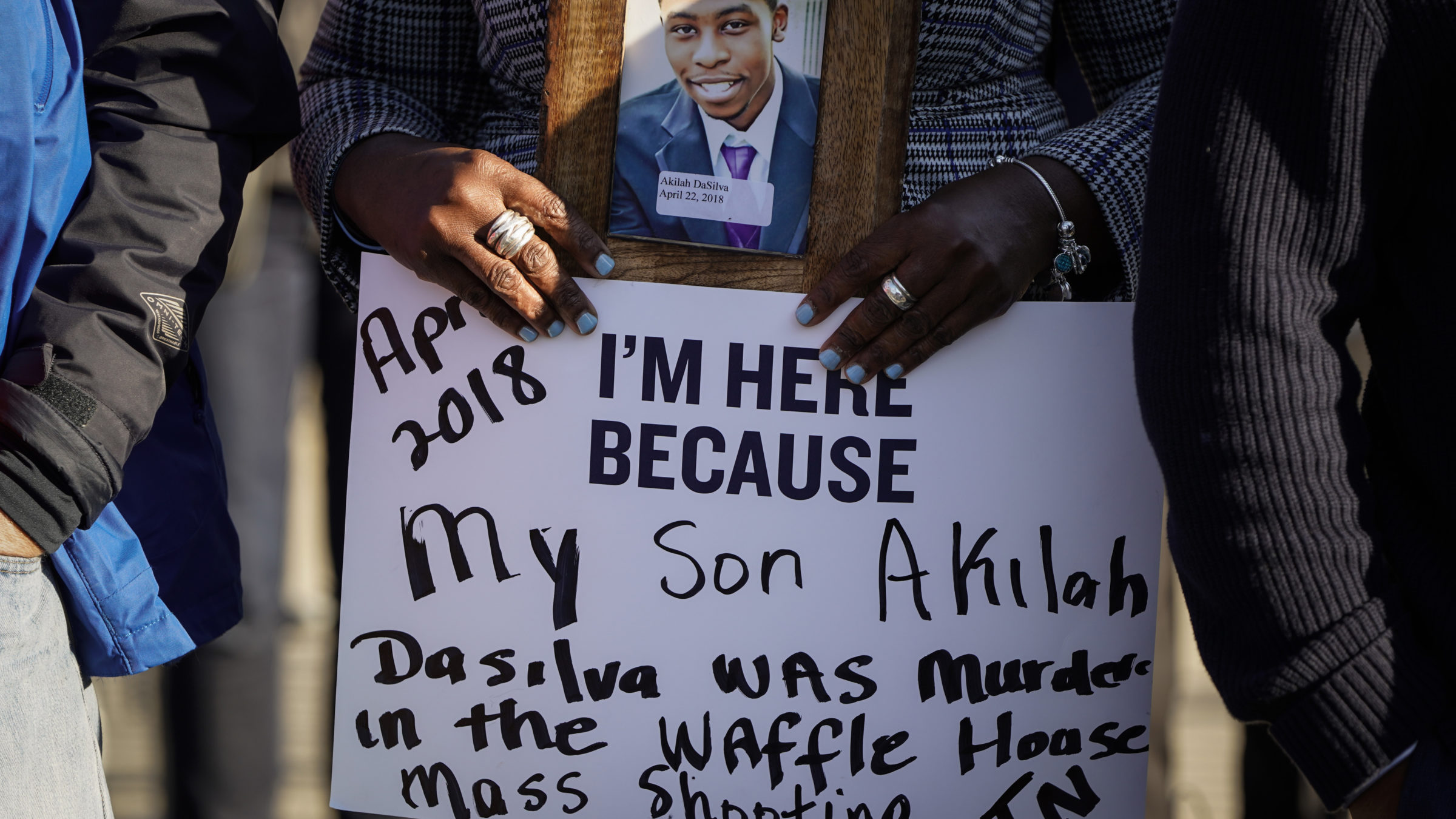

Sadly, any ruling offered by the Court will be disastrous for Black people. Suppose the Court miraculously retains the status quo, allowing state and local restrictions on carrying to stand. This still leaves a system that stratifies Second Amendment rights based on race, geography, and/or bureaucracy. Seven states that are home to approximately 80 million people—about a quarter of the country’s population—have similar laws in place, which force racial minorities to persuade bureaucrats that they are of sufficiently “good moral character” or have a “good and substantial reason” to carry a gun. Administrative discretion often invites race-based determinations, and leaves people who live in overpoliced or underpoliced neighborhoods all but powerless to protect themselves where the state fails to do so. As a matter of personal safety, particularly for victims of violent crime and their loved ones, this seems suboptimal.

Or consider a world where the Court extends the right to bear arms, allowing more people to carry more guns in more places. Black folks and members of other marginalized communities will bear the brunt of such a shift. Black women are disproportionately impacted by intimate partner gun violence. Women in the United States are four times likelier to be homicide victims than women in other high-income countries. Black men make up two percent of the U.S. population, but a whopping 37 percent of gun homicide victims. Besides the well-worn, dubious logic of “more guns equals less violence,” it’s hard to see how an expanded Second Amendment ruling in Bruen will solve these problems.

(Photo by Joshua Roberts/Getty Images)

It’s also not clear that a more expansive Second Amendment right would do anything about the problems that the challengers in Bruen are ostensibly trying to fix. Gun dealers, for example, have broad discretion to choose their customers. In theory, this allows them to decline to do business with people of whom they’re suspicious. In practice, this allows dealers to post “Muslim Free Zone” signs at their stores, and admit to refusing to sell to “two men with sagging pants,” purportedly after hearing about “all sorts of drama going town at their houses.” As I’ve written elsewhere, it’s not clear that prohibitions on discrimination in public accommodations like gun stores will solve such a problem, and it’s unlikely that this particular Court would bother itself with this kind of gun rights issue. An expanded Second Amendment would still be subject to arbitrary enforcement and illegal discrimination.

There is also little doubt that cops would continue to criminalize people of color for illegal gun possession, and if they somehow can’t do that in a new post-Bruen world, they’ll find another way to do so very quickly. One can only shudder at the prospect of police officers, who already say they feel threatened by Black skin, operating under the presumption that a Black person they encounter on the beat is legally strapped. As the historian Carol Anderson wrote in her book The Second, “From colonial times through the twenty-first century, regardless of the laws, regardless of the court decisions, regardless of the changing political environment, the Second has consistently meant this: The second a Black person exercises that right, the second they pick up a gun to protect themselves (or not), their life…could be snatched away in that same fatal second.”

In an attempt to better define the scope of a Second Amendment right that it only recently articulated, Clarence Thomas and the Bruen Court will shape the future of gun ownership in America, delivering a likely victory to conservatives in one of their longest-running culture wars. For too many Black people, the consequences will be fatal.