Last week, despite the fervent wishes of Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch, the country avoided a federal judiciary-induced economic crisis. On Thursday, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that the funding structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is indeed constitutional, allowing the Bureau to go about its business of protecting consumers from the nation’s sketchiest and most predatory financial institutions.

The CFPB is a product of the Dodd-Frank Act, which Congress passed after the Great Recession to protect the public from the wheeling and dealing of unscrupulous Wall Street-types. Conservative activists who benefit from the aforementioned unscrupulousness have been trying to roll back those laws ever since. The case the Court decided on Thursday, CFPB v. Community Financial Services of America, offered the Court a back road it could use to get Republicans where they wanted to go.

CFSA, a trade association of payday lenders, did more than challenge a single CFPB rule. It asked the Court to hold that the way Congress funds agencies like the CFPB is illegal, and that the CFPB’s regulations—all its regulations—are illegal too. Under Dodd-Frank, the Bureau can request a budget of up to 12 percent of the Federal Reserve System’s total operating expenses as reported in fiscal year 2009, adjusted for inflation. CFSA argued that this scheme violates the Constitution’s Appropriations Clause, which requires that “no money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in consequence of appropriations made by law.” Federal courts have rejected previous challenges to the CFPB’s funding structure, but because of the Court’s six-justice conservative supermajority, CFSA figured that this time might be different. Mercifully, it was wrong, and the CFPB’s funding and rulemaking authority both remain intact.

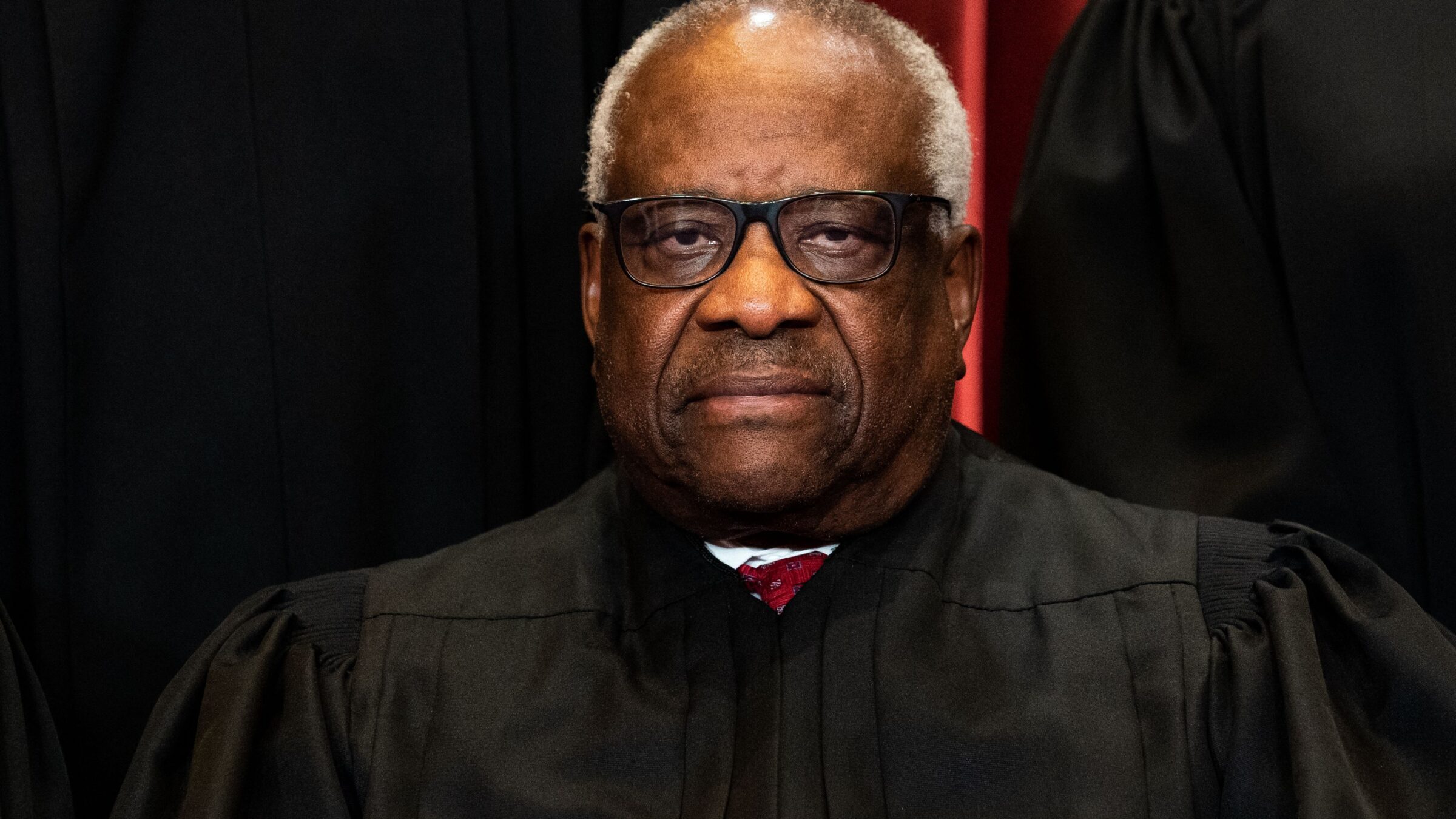

heartbreaking-the-worst-person-you-know.jpg (Photo by ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

The majority opinion was written by Justice Clarence Thomas. In standard originalist fashion, he purported to consult the text of the Constitution and contemporaneous sources to conclude that, in order to satisfy the original public meaning of the Appropriations Clause, appropriations “need only identify a source of public funds and authorize the expenditure of those funds for designated purposes.” Since “the statute that provides the Bureau’s funding meets these requirements,” Thomas wrote, the funding structure is constitutional.

Alito’s dissent, which Gorsuch joined, offers a dueling originalist account that reaches a very different conclusion: “The Framers would be shocked, even horrified, by this scheme,” he wrote. In support of his argument, Alito cites Georgetown Law Professor Josh Chafetz’s 2017 book Congress’s Constitution: Legislative Authority and the Separation of Powers, which details historical conflicts between the English Parliament and its Kings over the monarch’s financial independence, as well as the development of legislative control over the treasury via regular appropriations. Alito states, incorrectly, that Dodd-Frank empowers the CFPB “to draw as much money as it wants from any identified source for any permissible purpose until the end of time.” Thus, he declares, “it is not an exaggeration to say that the CFPB enjoys a degree of financial autonomy that a Stuart king would envy.”

The problem for Alito is, according to Chafetz, he didn’t understand the book at all. Chafetz specifically acknowledges in his book that the “text of the Constitution allows for indefinite appropriations in all contexts other than the army.” He also discusses the separation of purse and sword as a response to “fears of a tyrannical president,” which makes the Appropriations Clause a legislative check on the executive rather than a judicial check on the legislature. Finally, Chafetz details that early congressional appropriations were at times brief and nonspecific—just allocating a pot of funds for a broad purpose. Congress determined the amount of the CFPB’s annual funding by creating a statutory cap, just as the very first congresses sometimes did.

This is not the first time Supreme Court justices have made originalist arguments that befuddled people who actually know a thing or two about the time period. For example, the American Historical Association and the Organization of American Historians jointly characterized Dobbs, the opinion that overturned Roe v. Wade, as dismissive of reality. Legal history expert Saul Cornell similarly wrote that Thomas’s decision in Bruen, which invented a constitutional right to individual gun possession, took “law-office history to a new low.” As the historian Josh Zeitz wrote in Politico in 2022, the idea behind originalism “requires a very, very firm grasp of history” that “none of the nine justices, and certainly few of their 20-something law clerks, freshly minted from J.D. programs, possess.”

The concurring opinions chart out methods of decisionmaking other than strict originalism. Justice Elena Kagan, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, takes a longer look at history mixed with a dash of pragmatism. “The founding-era practice that the Court relates became the 19th-century practice, which became the 20th-century practice, which became today’s,” Kagan wrote. For her and three other justices, a “reason to uphold Congress’s decision about how to fund the CFPB” is “the way our Government has actually worked.” In a solo concurrence, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson emphasized that the political branches of government must be free “to address new challenges by enacting new laws and policies—without undue interference by courts.”

Conservatives like Thomas and Alito insist that squabbling over the past is the only appropriate way to assess the Constitution’s meaning. But the justices aren’t trained in history, and actual historians are becoming adamant in real time that the justices aren’t any good at it.