Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson made waves earlier this month when she used her perch to offer a vision of racial equality that stands at odds with how the Supreme Court often treats matters of race. The justice’s lengthy remarks, which came during oral argument in Merrill v. Milligan, an important redistricting case that could weaken the Voting Rights Act of 1965, felt like a mini-history lesson on Reconstruction and the constitutional amendments that were ratified during that period. “I don’t think that the historical record establishes that the founders believed that race neutrality or race blindness was required,” she said.

Jackson’s colloquy drew praise from commentators, some of whom noted that she was employing “progressive originalism” to advance a robust defense of racial equality under the law—which the Supreme Court has all but declared must be colorblind and not give a boost to people who have been historically marginalized on account of their race. With affirmative action in the sights of a reactionary supermajority, her insights on the Fourteenth Amendment may prove ever more valuable.

Beyond legal doctrine, I wanted to know what Eric Foner, one of the nation’s foremost authorities on Reconstruction, thought about Jackson’s take on this history. “I am of two minds about Justice Jackson’s remarks,” he told me in an email. “I am not a believer in originalism and do not want to operate on terrain constructed by the conservative justices. Originalism is intellectually indefensible. But if you are going to talk about history you had better get it right, and she does a much better job of that than those who believe the architects of Reconstruction were colorblind.”

There was a lot to unpack there, so the two of us spoke on the phone to talk some more about Jackson, the sham of originalism, the current Supreme Court’s selective reading of history, and what he might tell the liberal justices if he had their ear.

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Why is originalism problematic from a historical perspective?

Eric Foner: There is no important document in the world that has only one original meaning or one original intention. Let us take the Fourteenth Amendment: It’s ambiguous. It is full of generalities—general principles, which is fine. They have to be worked out, whether it’s “due process of law,” or “privileges and immunities.”

Those phrases meant a lot of different things to a lot of different people. These things were fought over. They were contested. And one of the points I make when I write about this is that the whole search for this generally looks purely at the debates in Congress, and therefore completely eliminates any Black voice. What did African Americans who are the subject of the Fourteenth Amendment in many ways—what did they think these ideas these phrases meant? And what did they think of the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment? Without Black legislators in the South, under Radical Reconstruction, voting to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, there would be no Fourteenth Amendment. And they must have had their own ideas about what they were doing, what they were trying to accomplish.

But you never get that in these discussions. And I just think it’s a misconceived effort. There’s nothing wrong with figuring out what people were trying to do. That’s part of the historical effort to understand the time period. But to think that there’s one original meaning is just foolish, in my opinion.

So you wouldn’t even concede the point that originalism is a tool rather than the tool to interpret the Constitution.

[Laughs] You know, I’m not a lawyer. I’m not a law professor. I’m not a constitutional scholar, although I play one on TV sometimes. But, you know, people can use all sorts of tools. But even if there were a single original intent, I don’t think we should accept the premise that that is what should govern an essential part of our political and legal system right now. I’m a believer in what they call the living Constitution; you apply these principles at the present, not by going back to figuring out what in 1866 Senator Jacob Howard or Charles Sumner, or for that matter, Jefferson Davis thought about what the Fourteenth Amendment meant.

And the idea that in the Dobbs decision, that somehow we are excluded from policies that didn’t exist a century and a half ago, is completely antidemocratic. But that’s what the Supreme Court says on gun control. Justice Thomas’s opinion [in Bruen, which expanded the Second Amendment right to bear arms in public spaces, says], “No, well, they didn’t pass the kind of laws that they passed now back then. So we can’t do it now.” Ridiculous, in my opinion.

I’m glad that you brought up Dobbs. Let’s talk about that a little bit. Because if you read Justice Alito’s opinion, there’s not even a pretense that it’s a so-called originalist opinion. He goes through some doctrinal legal analysis, but there was nowhere even an attempt to define what liberty in the Fourteenth Amendment means. And for that reason, then you wonder: What are we even doing here?

It’s a kind of reverse originalism, that decision. It’s just saying, “Well, the absence of pro-choice legislation 200 years ago should determine what we do now.” So, yeah, I think it’s ridiculous that it’s a straitjacket on public policy. But this seems to be where we’re heading. What about the right to privacy? Does that exist? It’s not mentioned, as we all know, by a word in the Constitution, but it’s become part for the last 50 years of our concept of law and politics.

The Dobbs opinion makes clear that the conservative justices pick and choose what they want the Constitution to mean, based on the policy outcomes that they prefer. What do you make of this current of progressive lawyers and academics who perhaps want to play on that terrain with the conservative justices, and try to divine a progressive understanding of the Constitution on originalist grounds. Is that a fool’s errand?

Yeah, in my humble opinion. Not because it isn’t logical, in many ways. I just got in the mail that book … What is it called? I have it right here on my shelf. Yeah, The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution, by William Forbath and Joseph Fishkin, and that’s exactly what you’re talking about. Is that good history? I’m not sure—I respect them very much. But I’m not a constitutional historian.

My point is, there is a lot of leeway within the Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment and the Thirteenth Amendment, actually, for public policies far more far-reaching than this court would ever agree to. And of course, every one of those three amendments ends with a section saying Congress shall have the power to enforce this amendment. Not the Supreme Court, not the secretary of state or somebody — Congress. But over time, the Supreme Court has asserted its right to overrule what Congress decides, even though the Constitution textually, specifically gives it to Congress.

It’s pretty clear why: They didn’t trust the Supreme Court. How could you trust a body which had produced the Dred Scott decision not that long before? They didn’t want the Supreme Court meddling around with what Congress decided was necessary in order to uplift former slaves into equality. But that’s what’s happened.

If that’s the case, Congress should consider other laws. But if they’re all going to get knocked down by the Supreme Court, then I guess it’s not worth the time to pass these laws. In my book on these three amendments, I pointed to a very long book, published in the 1880s, by a group of Black lawyers, severely criticizing the Supreme Court and its interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment and putting forward a different vision. You know, a different vision of things like the right to employment, the right to an education, as being part of liberty and privileges of citizens and things like that.

That’s part of the original intent, also—part of the original debate. We can choose which part of the historical record we want to emphasize and act on. That’s why I don’t like this originalist thing—because it’s a straitjacket limiting public policy.

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Since this reading, or this interpretive method, is a straitjacket, as you put it, then how — and you’ve already told me that you’re not a judge, or a legal scholar — but how should then a liberal vision of the Constitution be? How should they interpret these amendments?

The Warren Court did a pretty good job of that. They took these principles—not the specifics, the principles—and said, “How do we apply that principle at the moment, at the current time?” How these originalists can accept Brown v. Board of Education has always been very mysterious for me. You know, it’s not an originalist decision. In fact, the Supreme Court explicitly said—[Chief Justice Earl] Warren explicitly said, “We don’t know what the people intended in 1866. We’re interested in what we should do now.” That’s how I would interpret it.

And as you put it yourself, in your own writings, the people who ratified the Reconstruction Amendments seemed to be fine with segregated schools, so long as Black kids also had a shot at it.

Yeah, but why should that lead us to say, “Well, schools are fine in 2000,” or something? But again, whose intent is it really? Or whose originalism? Is it just judges of the time? Or just members of Congress of the time? One of my favorite quotes about Reconstruction was printed in the autobiography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, where she says that Reconstruction was a time when the fundamentals of government were debated all up and down the society, in churches, at every fireside—people were debating these things in their homes. And yet you never get a sense of that—that they were trying to work out what these principles meant. And there’s no single original meaning that one can devise out of this. Unfortunately, I’m not one of the nine people figuring this out.

And yet let’s try to be strategic here: If you had the ear of Justice Jackson and the two other liberal justices, what would you tell them, besides don’t play with the master’s tools?

I’m a historian. I’m certainly not going to tell them, “Don’t look at history. Don’t think about history.” As [Justice Jackson] points out, the history of the Reconstruction Era is something everybody should know about. And if you’re interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment, you really need to know what was going on in the country in the aftermath of the Civil War and the end of slavery.

But I would say this: Don’t accept the premise that that is the grounds on which we can determine whether a piece of legislation is legitimate or not.

This came up at the argument in Merrill v. Milligan, and it’ll come up again later this month when the court considers affirmative action policies. Why is it that, at least among the conservative justices and lawyers, this idea of colorblindness in the Fourteenth Amendment holds so much appeal?

It holds appeal because it’s a way of sticking it to the liberals. After all, it’s [Justice John Marshall] Harlan, who used that phrase in a dissent [in Plessy v. Ferguson, which rendered separate-but-equal accommodations constitutional]. One thing that’s not mentioned is the Supreme Court has never decided that the Constitution is colorblind—there’s never been five people who have said, “No, the Constitution is completely colorblind.” There may be now. But it’s their way of blocking or preventing any kind of affirmative action, so to speak, to uplift. They’re not interested in trying to uplift the status of African Americans in this country. And this gives them a weapon. Because it’s very hard to argue against it — “Oh, no, yes, the Constitution actually should be color-biased, it should be in favor of one group by color and not another.” It’s very hard to argue against the abstraction of colorblindness.

There were plenty of people during Reconstruction, who, yes, thought that the law and the Constitution should be colorblind. On the other hand, as [Jackson] points out, there were plenty of people who thought specific laws trying to assist the former slaves were totally legitimate under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Colorblindness is not the only original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. It was the original meaning in the eyes of some people, but not a lot of others.

One phrase that Justice Jackson used in her colloquy during the Milligan argument was that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was meant to ensure African Americans would have the same rights as those “enjoyed by white citizens.” And that itself is almost a rejection of colorblindness, because it uses race to uplift the race that was historically left out.

That’s a very good point. I mean, that’s an amazing thing in that law—it’s an amazing law to begin with.

But yes, to say that all citizens must enjoy the same rights as white persons was a complete repudiation of the history of the United States up to that point. Up to that point, white people enjoyed far more rights than any other group of people had. For the law now to say, “No, no, you can’t do that”—whiteness now becomes not a form of exclusion, but a standard that must apply to everybody. You want to know what basic rights in terms going to court, or testifying, or whatever, that non-whites should enjoy—look at what white people have. And then that’s the same thing that non-whites ought to have.

That’s certainly color-conscious. But you know, most people don’t even know what’s in the Civil Rights Act of 1866. So I’m glad she reminded people of that.

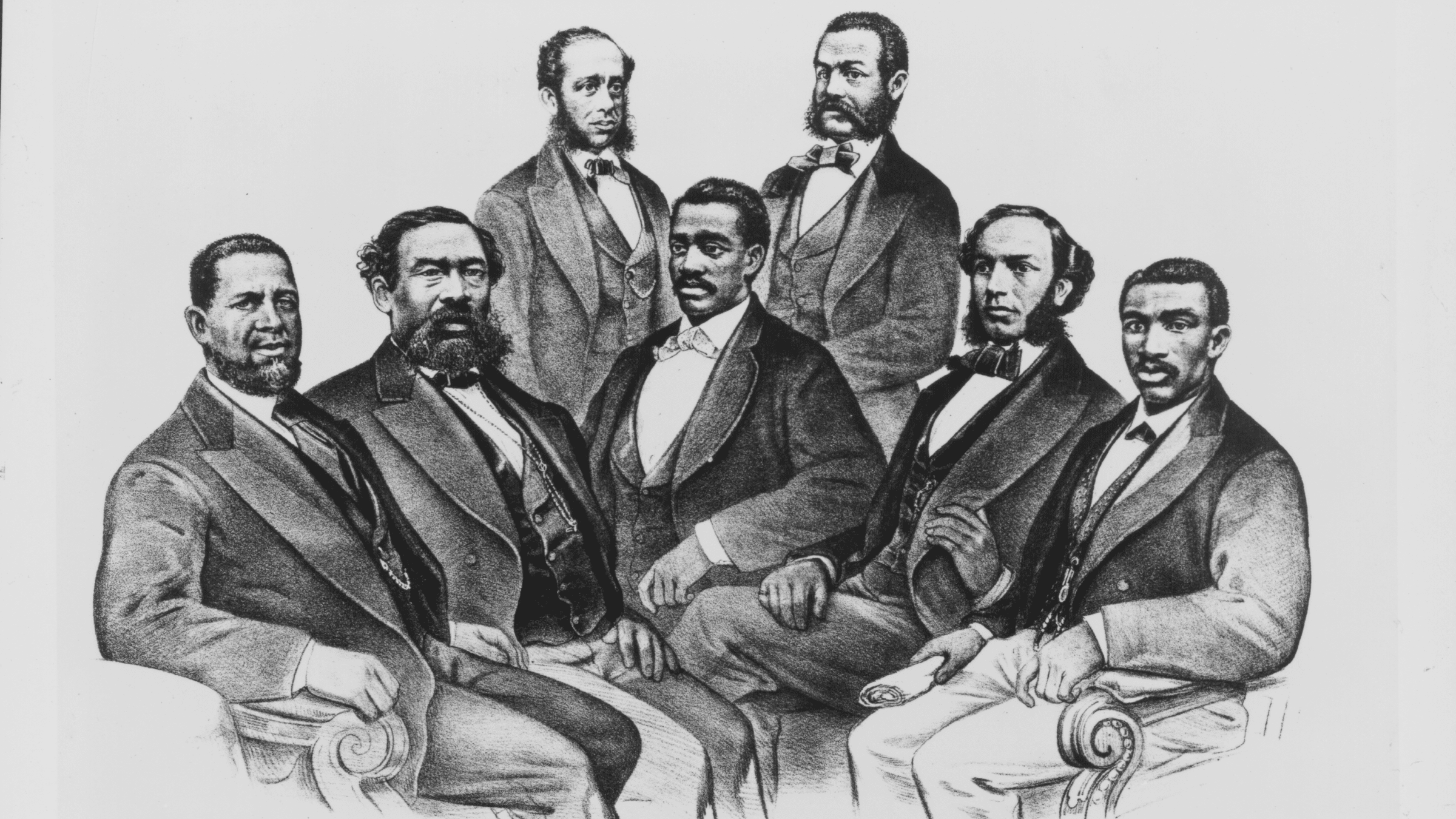

Group portrait of the first Black Senator, H.M. Revels of Mississippi, and Black members of Congress, 1871 (Archive Photos/Getty Images)

The current justices, both so-called originalists and the ones that are not so committed to that project—are there any analogues with the Reconstruction justices that you could think of? Are they similar or different from how the Court operated in the era?

It was so different back then. The Court didn’t exercise nearly the power—people didn’t say, “Oh, well, let’s see what the Supreme Court says,” you know? The Supreme Court was a much more minor institution at that time. And the justices—a couple of them were still on the Court who had voted in the Dred Scott decision. Most of them by this point were Republicans, but of various stripes. They were feeling their way, just like everybody else. One of the worst decisions of that period came really early, the Slaughterhouse decision in 1873, which kind of cut off the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Thomas is an interesting guy. Thomas wants to get rid of Slaughterhouse and resurrect the Privileges and Immunities Clause, which I would like to think on also, because I think that opens the door for many assertions of people’s rights. Thomas probably feels the same way, but he’s more interested in other rights than I am.

I don’t think he’s really interested in applying that clause to, say, undocumented immigrants.

No, hardly. But I think that clause opens up all sorts of possibilities. What are the privileges and immunities of citizens? Let’s take one example, which was actually debated a lot at that time: the right to an education—that the right to an adequate education is a privilege of citizenship, and it must be enforced in the states. And the Court has never gone anywhere near that.

But remember, they’re in the shadow of slavery. The denial of education, of literacy, to slaves was one of the many atrocities under slavery that was on their mind. You want to be an originalist? Go back and look what Jacob Howard said about this. But, you know, the Court has never wanted to go down that road.

Perhaps a project for Justice Jackson, especially in this moment of retrenchment, if she’s interested to look to the future for a counter-counterrevolution, would be to look at the works of those Black intellectuals and radicals from Reconstruction and try to revive some of that project.

That’s what I call for in my book on all this, The Second Founding. It ends by saying that there are other visions of jurisprudence out there, rooted in the history, not just made up out of whole cloth. And one of these days, maybe the Supreme Court will rediscover that jurisprudence. I’m not too optimistic right now. But you never know.

I’m not optimistic either. And to be clear, maybe she has to use the podium and her dissents to articulate it. That’s the only way.

Absolutely. She’s got two brilliant colleagues—[Justice Elena] Kagan and [Justice Sonia] Sotomayor. All of them know this history very well. But, as I said, I don’t believe that that is the determining factor in what legislation is allowable under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Those amendments can be resurrected. There is no reason they shouldn’t be resurrected as much more vigorous assertions of the basic rights of all Americans, but particularly the descendants of former slaves.

This conversation is a co-publication with The Emancipator, a project of The Boston Globe. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.