The death penalty is still on the books in around half of U.S. states. But since 1972, juries in only 34 of the country’s 3,000-plus counties have imposed nearly half of all death sentences to people awaiting execution on state death rows. That means only 1 percent of counties have sentenced thousands of people to death. More than 80 percent of counties didn’t send anyone to death row during that same period, according to the most recent end-of-year report published by the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC).

The Supreme Court has long held that the government cannot administer capital punishment in an arbitrary fashion. But the DPIC’s analysis shows that whether a person convicted of a crime will face death at the hands of the state depends heavily on geography—on the invisible borders of the state and county in which the crime happens to have been committed.

Oklahoma and Texas are especially egregious offenders. Together, these states are responsible for 697 of the 1,558 executions that have taken place since 1976. Just five counties—four in Texas, one in Oklahoma—are responsible for almost half of those 697 executions. Texas’s Harris County, which includes Houston, leads the pack with 131 executions—nearly twice as many as the next county on the list. Even as large swaths of the nation have abandoned the death penalty altogether, a few holdouts continue to administer it with fervor.

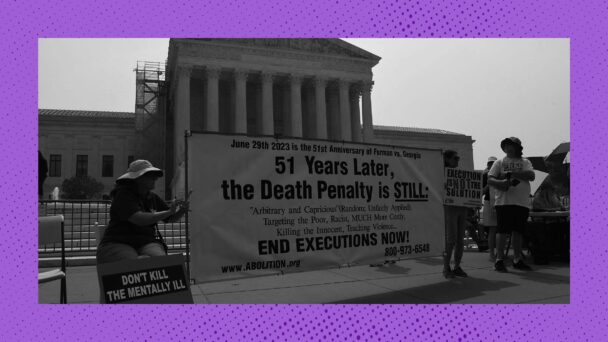

The Court has gone back and forth about the constitutionality of the death penalty, briefly banning it in 1972 on the grounds that the government could not impose it in an arbitrary and capricious manner. “The State does not respect human dignity when, without reason, it inflicts upon some people a severe punishment that it does not inflict upon others,” wrote Justice William O. Douglas. But four years later, in Gregg v. Georgia, the Court ended its de facto moratorium after Florida, Georgia, and Texas amended their sentencing procedures to the justices’ satisfaction. They have not seriously entertained a facial challenge to the death penalty since.

The trends the DPIC identified aren’t new. In his dissent in Glossip v. Gross, which the Court decided in 2015, Justice Stephen Breyer highlighted the “important role” of geography in determining who receives the death penalty—not only state by state, but also county by county. “Between 2004 and 2009, for example, just 29 counties (fewer than 1% of counties in the country) accounted for approximately half of all death sentences imposed nationwide,” he wrote. “And in 2012, just 59 counties (fewer than 2% of counties in the country) accounted for all death sentences imposed nationwide.”

Breyer, a consistent skeptic of the death penalty while on the bench, blamed multiple factors for the death penalty’s inconsistent application: the power of local prosecutors, weak public defense systems, the county’s racial composition and distribution, and tough-on-crime political pressure on elected judges. Prosecutors’ offices with higher budgets are indeed more likely to seek the death penalty. And Breyer pointed to research showing that counties with higher death sentence rates tend to have under-resourced and overwhelmed public defense offices—or no public defense office at all.

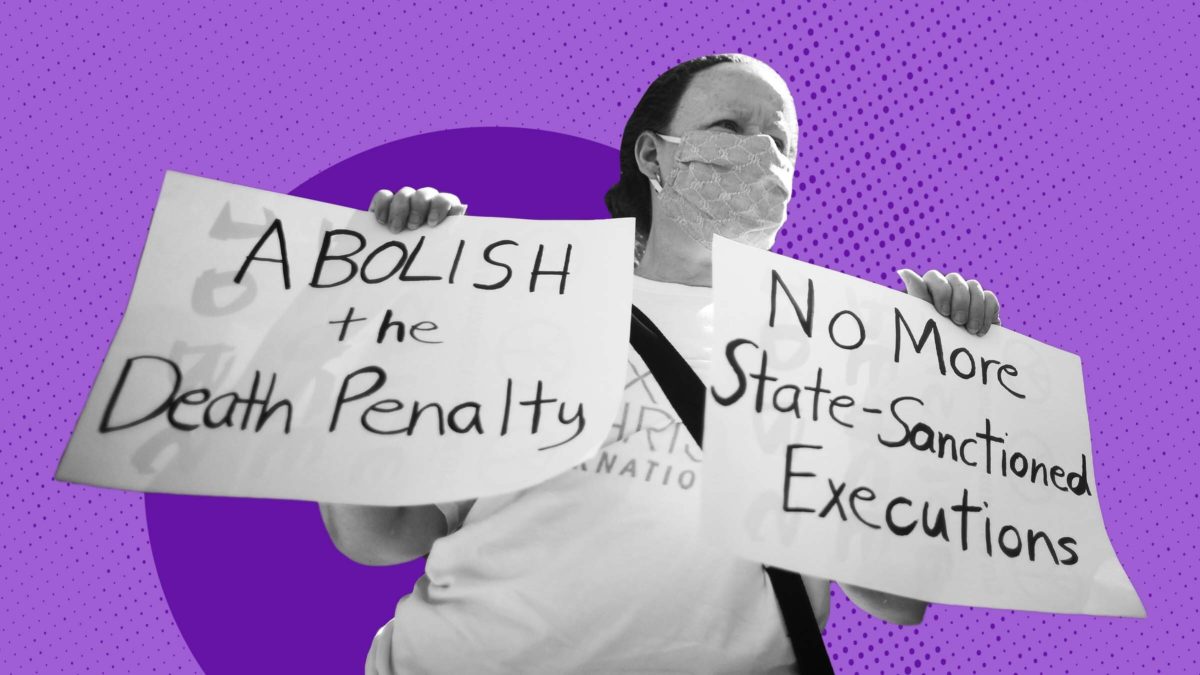

If the Court were committed to preventing the capricious administration of state-sanctioned death, it would take seriously the glaring evidence of the death penalty’s inconsistent administration. But even in the face of data like this, a majority of the Court does not share Breyer’s concerns. Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion in Glossip ignored Breyer’s argument altogether and simply reiterated the Court’s previous holdings that the death penalty is not per se unconstitutional. For him, if moving forward with a regime of state-sanctioned executions requires accepting some degree of arbitrariness in its implementation, so be it.